Remember the “Shit People Say” phenomenon?

A couple of comics from Toronto created the Twitter account @ShitGirlsSay in 2011, which eventually spawned a YouTube series and what felt like a few thousand spinoffs over the course of a year or so until it trickled off.

Know Your Meme labeled it one of the “Notables of 2012” along with Texts From Hillary, Overly Attached Girlfriend, Kony 2012, and many others.

But one of the biggest trends to start 2013, the Harlem Shake, trickled out after a month. Now, you’re lucky if something lasts on the Internet for a week.

in 2013 it could be a year

— goodinthestacks (@goodinthestacks) November 4, 2014

And then there’s the catcalling video.

On Oct. 28, we were introduced to the catcalling video from the nonprofit Hollaback and Rob Bliss, who runs a viral marketing agency. They recruited an actress, one who’s experienced street harassment on just about a daily basis, to walk behind a GoPro camera silently for 10 hours, and filmed it. What ensued was outcry and backlash from (mostly male) viewers, essays about racial disparities, and commentary on cable news shows.

And over a week after “10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman” debuted on YouTube, it’s still fresh in viewers’ minds, thanks in part to countless parody videos that have sprouted up since its release. Here’s what’s wrong with that picture.

•••

The response video of what it’s like for a man to walk through New York City was practically a no-brainer for sketch comedians, and it only took two days for the first wave of parodies to hit, thanks to some quick production from Funny or Die.

It might not have been the first, but it was probably the first major parody to catch the Internet’s eye; it’s been viewed more than 6 million times on Funny or Die alone. Soon enough, we started spotting even more parodies.

i cant wait to see the hilarious parody videos men will inevitably make of the 10 hours in new york thing

— thomas violence (@thomas_violence) October 30, 2014

i imagine that right now you can’t walk down a street in new york without running into someone filming a “10 hours” parody video

— Steve Spillman (@spillman) October 30, 2014

You can now see what happens to a female character in Skyrim, a support in DOTA 2, a drag queen in Los Angeles, a Jewish person in New York, a hipster in Austin, and, for some reason, a horse. There’s plenty floating around the Internet using the same concept. Some feature men, some star women, and still others reference video game characters.

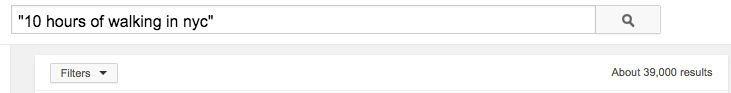

Curious as to how many of these videos were out there, I did a quick search on YouTube.

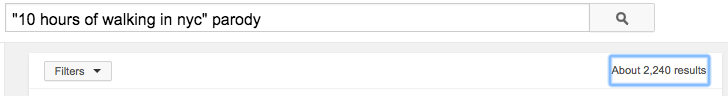

With mirror uploads, news coverage, commentary, and reaction videos accounting for a number of those results—and recognizing that my search may have been vague, I tried narrowing it down a bit.

It’s possible that the narrow search could be overinflated with mirrors, but it still means that a bunch of people saw that catcalling video and—maybe after an initial reaction of anger, doubt, or incredulity—thought to make a parody video with a disclaimer of not intending to make any statements about the original catcalling video. That’s like uploading a Taylor Swift song straight to YouTube and adding, “no copyright infringement intended” in the description. That’s still copyright infringement, and you’re still making a statement about the original video, whether you intended to or not.

•••

A few months ago, I sat in a panel called “Intentional Virality” at VidCon and listened to some rather successful content creators talk about what makes a video go viral.

Having written about quite a bit of viral content—both things that come out of nowhere and the consistent late-night talk show circuit—I was doubtful and rather cynical about it. If you see enough Jimmy Kimmel pranks floating around the Internet, you start assuming that everything that goes viral is fake, and you’re only joking part of the time. My bar for laugh-out-loud funny is set higher than most people’s, and I get more irritated easily by such content; I started tiring of Frozen parodies in January, and it took a girl singing about poop for me to warm up to them again.

Cynicism aside, it turned out to be a somewhat fascinating discussion, as the men behind the viral curtain spilled some of the tricks of the trade.

“The most viral stuff are things that anybody can share, connect with,” MinutePhysics’ Henry Reich told the audience.

Sometimes all it takes is to put a piece of content with a clever title on Reddit for it to go viral, but Reich, along with the other panelists, broke down what generally works for them and what they’ve seen work. If you make a video that follows up with something that’s already popular (like a parody) or tent-pole off trending videos, your chances of going viral are greater (though actual mileage may vary).

They also discussed video packaging and getting it to the right community, but the only problem for them is the window for parody is getting smaller every day—as well as people’s tolerance for them.

•••

My perception of what comes and goes online may be skewed slightly by being sucked into the circlejerk that is Media Twitter. There, jokes live and die by the RT and fav, and sometimes it only takes minutes for the entire lifespan of a meme to transpire. I can tune out Twitter to write an article, grab lunch, and come back, and I’ve already missed the next big thing everyone’s mocking.

Major events excluded (when the Internet’s comedy game is fully on), the cycle of virality doesn’t last nearly as long as it used to. More people jump onto the coattails of something viral as quickly as they can, only to fall off as it fades away into Internet obscurity. For me, it was slightly surprising, from a solely viral aspect, that people were still talking about the catcall video a week later.

From a cultural standpoint, I completely understood.

Reactions to catcalling parody videos have been mixed. When writing about Funny or Die’s video, HuffPost UK’s Brogan Driscoll called the video misogynistic and described it as being “not only … unremarkably unfunny but it completely undermines the entire premise of the original video.”

Less popular parodies received similar criticism. For example, take the Skyrim video. The female character appears to have a physics extension added to it to make her breasts bounce for no reason. The drag queen video makes light of situations that many in the LGBT community face on a daily basis. Even a video showing what a woman would do (or should do) to catcallers undermines the women who are too afraid of being murdered for speaking out or rejecting someone’s advances.

Are they highlighting street harassment or just mocking the very people who are being harassed (or claim to be, according to naysayers)? Regardless, it rubs me the wrong way, and not because I don’t have a sense of humor.

They’re largely not funny, and when it comes to a big social issue like this one, they don’t really promote any productive conversation. No matter how many disclaimers you put on a video, you’re saying something when you make a video miming it. Some will always ultimately be sexist and offensive.

The issue with parody videos didn’t just suddenly appear when a GoPro camera captured a day in a woman’s life, but it’s highlighting it more than ever. It’d be easy to tweet out “BAN PARODY VIDEOS” in anger, but I’ve been on the Internet long enough to know that’s never really going to happen—and such a genuine insistence would probably make them become even bigger.

For the next time something goes viral long enough to warrant an onslaught of parodies, I’ve created some guidelines to potentially help the Internet create something less shitty, offensive, and mocking.

1) Has it been done before?

Seriously. Go dig around YouTube or Reddit for about 10 minutes before making a video. Do you see at least a dozen videos with the same exact concept that you had in mind? Your idea may be better than theirs, but go back to the drawing board anyway and come up with something even better. It’ll just get lost in the woodwork of all the other videos.

Consider “Weird Al” Yankovic, one of the original kings of parody: He did “Blurred Lines” about a year after the rest of the Internet got their hands on it. Instead of focusing on an easy target like the misogyny and rape culture in it, he came up with a completely different twist, and it worked for the better.

2) Does it only portray stereotypes?

Target the right audience and you’ll get laughs, but you’re showing utter laziness when you rely on stereotypes. It’s boring, dirty, unoriginal, and not even funny. Look no further than the many stereotypes of men and women during sporting events. It’s the same shit every year, and you’re going to get a healthy amount of backlash for sexism. As you should.

An exemption to this rule is if it’s used to start a bigger conversation, such as Francesca Ramsey’s “Shit White Girls Say…to Black Girls.”

3) Does it add nothing to the conversation at hand?

Or, “Is your video a carbon copy of the original but with one or two things changed for humor only?” If the answer is yes, brainstorm again. You’re more creative than that.

4) Does your video undermine the point the original video was trying to make?

Making a mockery of the original video only makes you look like a fool, and it derails the initial conversation started by the video in question. They’re the “not all men” of parody videos. Instead of talking about street harassment, we’re now talking about the sexist nature of the parody videos.

5) Does someone outside of your immediate circle of family and friends find it problematic?

It’s probably a good idea to get someone who isn’t afraid to tell you if something is terrible or someone who has a different mindset from yours to hear out your plan. They can often see something wrong with it that you may miss.

If you answered yes to many of these questions:

Come up with a new idea—or better yet, don’t. It’s likely already out there and done terribly.

Screengrabs via Street HarassmentVideo/YouTube