My most popular YouTube video is 20 seconds long.

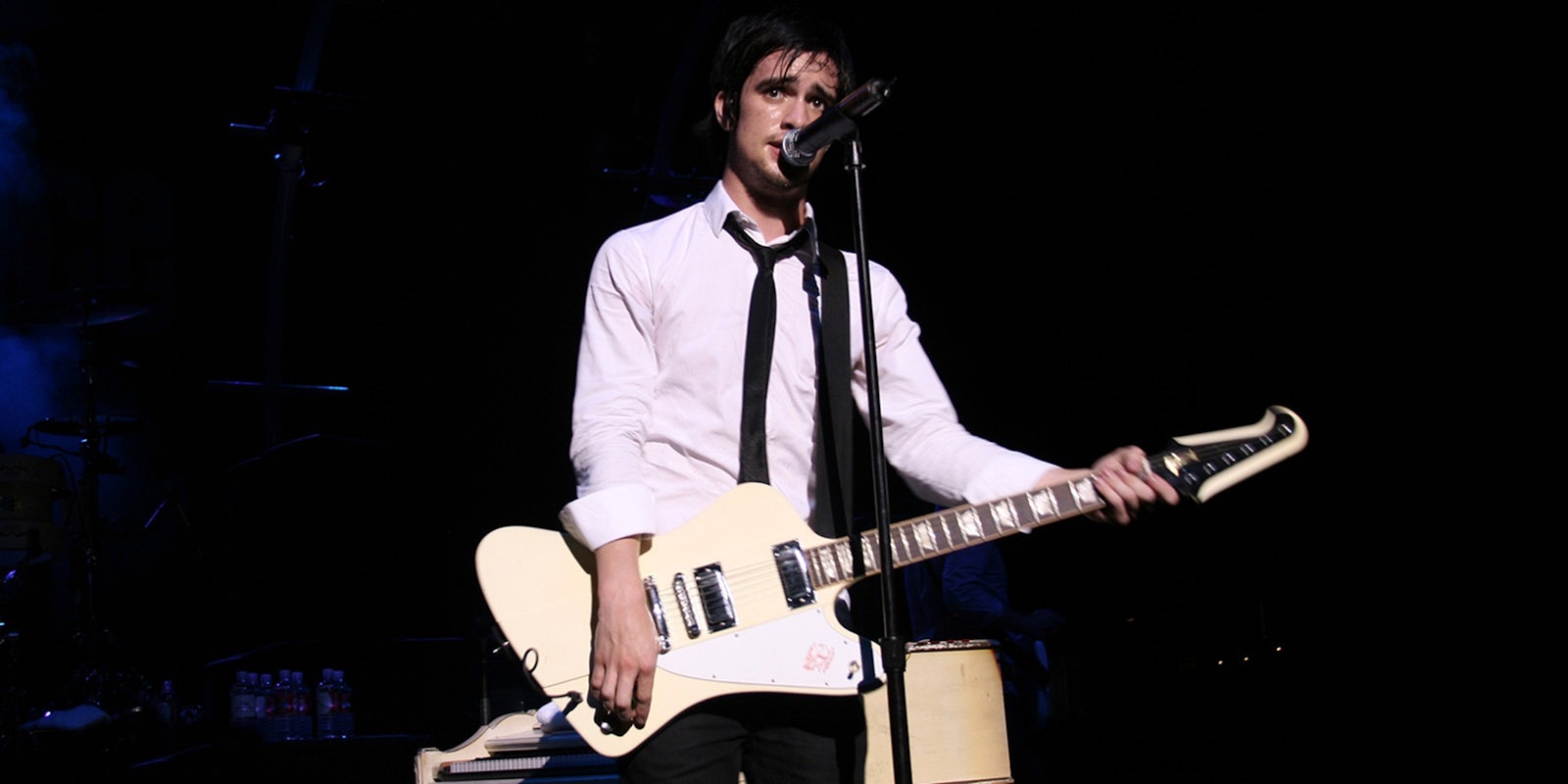

It was filmed in Portland, Oregon, toward the end of Panic! At the Disco’s second headlining tour in 2006. Lead singer Brendon Urie had been teasing in a bit of banter about a “perfect passionate kiss” right before the song “Lying Is the Most Fun a Girl Can Have Without Taking Her Clothes Off” by approaching guitarist and lyricist Ryan Ross, stroking his face, and leaning in, only to pull back at the very last second, the whole audience rapt and gasping.

This time, he didn’t really pull back.

They just touch foreheads, though. It’s pretty much nothing, but to this day it gets comments from Panic fans, many new to loving the band—or loving the imagined relationship between Ross, who left the band in an incredibly dramatic and wrenching divide in 2009, and Urie, who is the only original member left in the band today. But in 2006 the band intact, just a year into its career, mirroring another newcomer onto the pop media scene: YouTube.

In 2005 YouTube began streaming videos for the first time, and, just a few short months later, the band Panic! At the Disco released its first studio album, A Fever You Can’t Sweat Out. I didn’t realize that a decade later, the intersection of the two would influence my life so profoundly.

It’s hard to imagine a time when you couldn’t find the latest Beyoncé performance within moments of it happening with just a few clicks. Or even watch live, thanks to streaming apps. Before every phone was also a powerful camera, videos online were few and far between, even in the early days of YouTube.

The proliferation of social media and online video streaming opened up a whole new world for fans. For N*SYNC fans looking to see clips from arena tours, whole underground systems of file trading existed, with CDs full of MP4s available on order for affordable prices, mailed to you from a collector who created sets. TV clips from international stations and obscure live performances traded like precious gold. YouTube clicked on, and, once fans had their own super-powered recording devices in the palms of their hands, clips flooded the ecosystem.

In the early days, of course, the quality of those recordings was suspect at best.

In the early days, of course, the quality of those recordings was suspect at best. Even now, someone’s non-zoomed shot from the back of Madison Square Garden isn’t going to replace the live experience, or even get any attention from even the most diehard fans of an artist. But the closer you sat, and the better your angle and camera, the better the chance that your video might become “the video” that captured a moment.

The year of YouTube’s launch coincided with my first Panic! At the Disco concerts. Just a few months after my first taste of the band’s baroque, pop-punk style, I bought a fistful of early-entry tickets to their second headlining tour and camped out in the front row with my Sony digital camera in tow. From the back of the room, the quality would have been decent, but I was hips-flush to the barrier at every show I attended in fall of 2006, and I tallied more Panic! At the Disco shows than I’d seen of any other artists combined in the 23 years of my life prior. I’m the kind of person who goes all-or-nothing, and my headfirst fall into Panic fandom is a testament to that.

For those unfamiliar, Panic! At the Disco were a quartet of barely adults who were among the first musicians born on the Internet. As origin story goes, they pestered Fall Out Boy’s Pete Wentz through LiveJournal until he listened to a track, loved it, flew to see them practice in their hometown of Las Vegas, and signed them on the spot. They jumped in the studio and on the road with a handful of small shows under their belts and churned out what would become a Platinum-selling album and a music video that won 2006’s VMA for Video of the Year. They were the type to jump in headfirst too—possibly why they spoke to me so—and their first headlining tour included a giant windmill, acrobats, and elaborate face makeup and costumes. They also knew their audience of screaming girls screamed even louder when lead Urie flirted with Ross, and so they played a very long game of gay chicken, especially across their first two tours and subsequent one-off gigs from 2006 to 2008.

My YouTube channel is a deep catalog of this time for them. In my first forays, I never even posted full song clips. I was more interested in documenting the banter they were performing between numbers, cover songs they only played on occasion, or specific aspects of songs where they played out their homosexual flirtations that drove fans wild. I was one of those fans, desperate for queer representation in my media that explained my subsequent Glee infatuation, and diehard support of Adam Lambert’s run on American Idol in later years. Big poppy spectacle with a queer bent is my thing, and Panic had that in spades.

I had the benefit a front-row view, a quick turnaround for uploading my videos from each evening, and multiple stops on each tour to document. My standout 20-second non-kiss clip is far from my only well-trafficked one of the band. In fact, just behind it in views is a clip from eight days later, the final night of the tour, where Urie did kiss Ross before singing their mega-hit “I Write Sins, Not Tragedies.” It’s a smacking peck on the cheek, but it racked up 148,000 views.

Several of my clips topped 50,000 views at a time when today’s biggest YouTube sensations hadn’t even picked up a camera. (If they had, they were speaking to audiences of 20,000 viewers, maybe 100,000 at best. For scale, consider that PewDiePie, one of YouTube’s most-subscribed channels today, just notched his 10 billionth view. With a B.) I documented Panic religiously during my three years of solid devotion to the band, perfecting a method that balanced my camera up against my sternum so I could still watch and mouth along lyrics from the front row. After tours their team would ask me if I had captured a certain moment, telling me they watched my videos after shows when they knew I was there. It was like game tape, since I had such close vantage points.

I ended up in the right place at the right time: Press passes let me watch and film a whole show from inside the photo pit; a friend working for another band on the bill got me sidestage. Eventually I worked for their label, and it was that closeness to the belly of the beast (and the divide of the band into two factions) that actually broke down my fandom for Panic, and willingness to either document or attend their shows. My presence in the fandom had become a known entity, and I realized I didn’t want to be known, at least not for that. In 2009 I filmed my last clip of them (appropriately with my new iPhone) and then stopped filming them for good.

I barely touched YouTube in the years since, dropping off from the platform right around the time when it began to birth the homegrown celebrities I’ve gone on to cover for the Daily Dot. Luckily, YouTube kept a record of my fandom life, and the 77 individual concert videos I took during my YouTube heydey live on on my YouTube channel. It’s given me 1.2 million lifetime views, but none of them have even been monetized, by me or by any of the the bands I featured. They’re also far from perfect, and they decidedly pale in comparison to modern concert videos. The loud rock music blew out my microphones often, and I swung back and forth to capture all the action, keeping it just jerky enough to discount me as a serious videographer.

Now 13, she’s using my videos to build her own understanding of a fandom.

My passion wasn’t about professionalism, though. There was no real inkling of being “YouTube famous” in 2006 or 2007, as shocking as that is to present-day me, who spends her days covering the vast YouTube entertainer set. Monetization wasn’t a part of the early YouTube platform, so all those first clips were just free fandom property, skirting the line of legality. For me, that was the goal: to make accessible the somewhat inaccessible. Not every fan was privileged or determined like I was to see multiple shows, and commit to front row viewing (once, I stood front row with my foot in a boot following a minor car accident, earning shock and, I can only hope, respect from fans and the band alike.) I could help preserve a narrative, to keep a public record of a moment in time.

One of the most recent comments on a video from 2008 was from a girl who, in all caps, exclaimed that she was so sad that Panic had played Atlanta when she lived there, although she was only 6 at the time of the video’s filming. Now 13, she’s using my videos to build her own understanding of a fandom, to go through its history and canon and fuel her own obsession.

I may have moved on, but I’m happy my dedication almost a decade ago can help keep a fandom connected long after my time.

Photo via Rae Votta/Flickr (C, used with permission) | Remix by Jason Reed