There’s a scene early in Montage of Heck, director Brett Morgen’s documentary on Kurt Cobain, in which we see home video footage of the Nirvana frontman at around 3 years old, playing guitar and smiling. Elsewhere, he’s drawing. His mother says he was a hyper child. His sister Kim remarks she’s “so glad I never got that genius brain.” For those who know how the story ends, that comment is heartwrenching.

To fans of Nirvana, Montage of Heck is a goldmine of intimacy. Since Nirvana formed, there have been several attempts to tell the story of the band and Cobain’s legacy via unauthorized bios and documentaries, but none have the archival weight of Montage of Heck. Morgen was also behind the Robert Evans doc The Kid Stays in the Picture, and Montage of Heck has the same aesthetic, veering between animation, archival footage, and interviews.

The film is part bio and part ephemera: Morgen slowly pans across Cobain’s artwork, scrawled notebooks, and self-recorded audio clips, animated for maximum emotional effect. When the film debuted at South by Southwest in March, many viewers left Austin, Texas’s historic Paramount Theatre with tears in their eyes. Strangers gathered outside to talk about seeing Nirvana just blocks away at Liberty Lunch in 1991. The Nirvana fandom is a strong one.

We spoke with Morgen after the premiere, and he said his approach to the film was an “immersive experience that’s felt more than learned.”

The film progresses chronologically, exploring a childhood in which Cobain was tossed around between families and stepfamilies and a teenage existence of alienation and depression, expressed via his chaotic drawings and journals. Cobain’s first girlfriend, Tracy Marander, supported his art, and while they were living together in Olympia, Wash., in the late ’80s, he recorded songs that informed the 1988 “Montage of Heck” mixtape, which includes a devastating cover of the Beatles’ “And I Love Her.” (Morgen recently revealed he’s going to release an album of the home recordings this summer.) Around this same time, journal entries reference Cobain’s growing stomach problems, and we’re told he started using heroin as a palliative measure.

There’s a focus on Cobain’s sudden fame with Nirvana and especially his “spokesman” status, which was mainly ascribed to him by the media. And there’s a large volume devoted to his relationship with Courtney Love Cobain, whom many still blame for Cobain’s demise.

Kurt and Courtney’s public relationship was bookmarked by two magazine stories: an April 1992 Sassy cover that introduced the world to this new kind of power couple, and the damning September 1992 Vanity Fair article in which Love’s alleged heroin use while pregnant with daughter Frances Bean was used as evidence to take custody away after she was born. In the film, we get the context of that chaos, but we also get two people who grew up in isolating towns, converging in a supernova of love and fame and junk. In one scene, they read hate mail about the Sassy cover in their L.A. apartment, which you can now apparently rent on Airbnb.

In another clip, Cobain and Love stand naked in the bathroom, razzing each other. Elsewhere, Love talks about the media and how she’s the most hated woman in America. Cobain shoots back: “You and Roseanne Barr are tied for most hated woman in America.” We never see who’s filming when both are in frame; we’re just silently sitting in the dark watching them, and the intimacy is uncomfortable.

And you’re right to feel uncomfortable: Even as we attempt to unlock who Cobain was through his impressively archived art, words, and music, we still see him framed as a pained, mythological creature who burned too bright for this world. By passively viewing these home videos, can we truly experience what he was going through? Would he want us to?

“There was a conscious effort on my part to present Courtney through his eyes,” Morgen explained. “What I found in their private home movies was totally different than what [Vanity Fair writer] Lynn Hirschberg experienced, from what the public experienced. Lynn wrote about this sort of domineering woman and this meek guy, but I saw a very symbiotic relationship. I saw two kids who were 23 years old and in passionate, fiery love.”

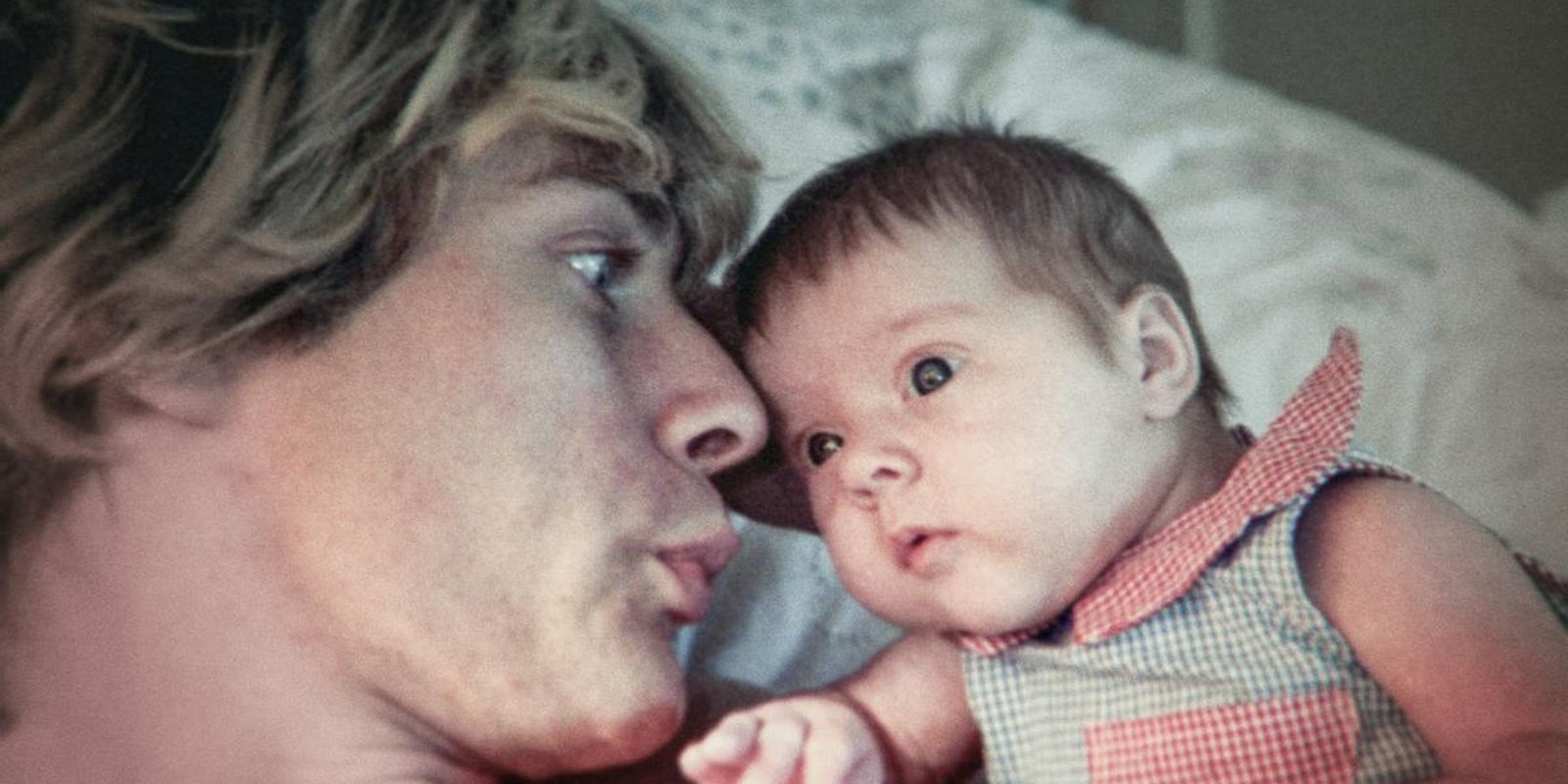

There’s a surprising amount of footage of him doting on his newborn daughter, who recently revealed she’s not really a Nirvana fan. In earlier clips, he stares lovingly at her with the kind of soft-eyed awe only new parents know. Toward the end of the film, there’s a scene in which Cobain is holding Frances as Love gives her a haircut. He’s clearly unwell, nodding off but trying so hard to keep his daughter in sight by singing to her. Morgen says it was important to show: “That scene isn’t exclusively about Kurt’s drug use,” he said. “It’s about a conflict between the love he has for his child and his addiction. In that one shot, you see how much he wants to be a doting father and how he’s let his addiction get the best of him.”

Frances doesn’t appear in the film, but she did executive produce it. Morgen explains that she didn’t know her father like the rest of the people in the film did, but she wanted it to be honest. And there are some very honest moments, like when Love casually comments that Cobain’s goal with Nirvana was to “earn $3 million then be a junkie.”

Love was the catalyst: She approached Morgen in 2007, and stated her case for doing a documentary.

“She said to me in our first meeting, ‘Everyone knows Kurt the singer, songwriter, rock star,’” Morgen said. “‘But what most people didn’t know was Kurt was an artist, and artist with a capital A.’ And she had all this material that she thought would warrant the basis for an interesting film experience. That was about eight years ago this week, and from there I went off on the journey.”

When Love and Frances offered him access to a storage facility, he says he expected to find art. He ended up finding a box with 108 cassettes, which is used as the soundtrack for much of the movie.

“Not only were there hours upon hours of Cobain material, a lot of which was in a completely different style than I’d experienced with Nirvana,” he said. “It was a lot of beautiful, acoustic music that we used as a sort of score throughout the movie. There was all this incredible spoken word and his audio autobiography of his youth. His cover of the Beatles’ ‘And I Love Her.’ Just this incredible stuff that really, to me, is what elevated the film, because Kurt was an artist first. And like all artists, he left behind this autobiography in this life. The fact that he worked in both visual and oral media meant it was one of the most complete visual and oral autobiographies.”

As I stood in line for the movie at SXSW, I noticed there were people waiting alongside me who were likely born the year Cobain died, who didn’t get to experience Nirvana as a teenager like I did. And yet, Cobain’s influence continues with a new generation that’s found intimacy and solace in Nirvana’s music.

“Kurt represents the misfits, the geeks, the ugly, the downtrodden, the disenfranchised,” Morgen said. “That’s how it’s been since 1991. It doesn’t surprise me at all that his music transcended various generations. … He provides comfort through his music to people who feel alone. I think it will hopefully carry forth for several generations.”

Montage of Heck debuts May 4 on HBO.

Photo courtesy of HBO Documentary Films