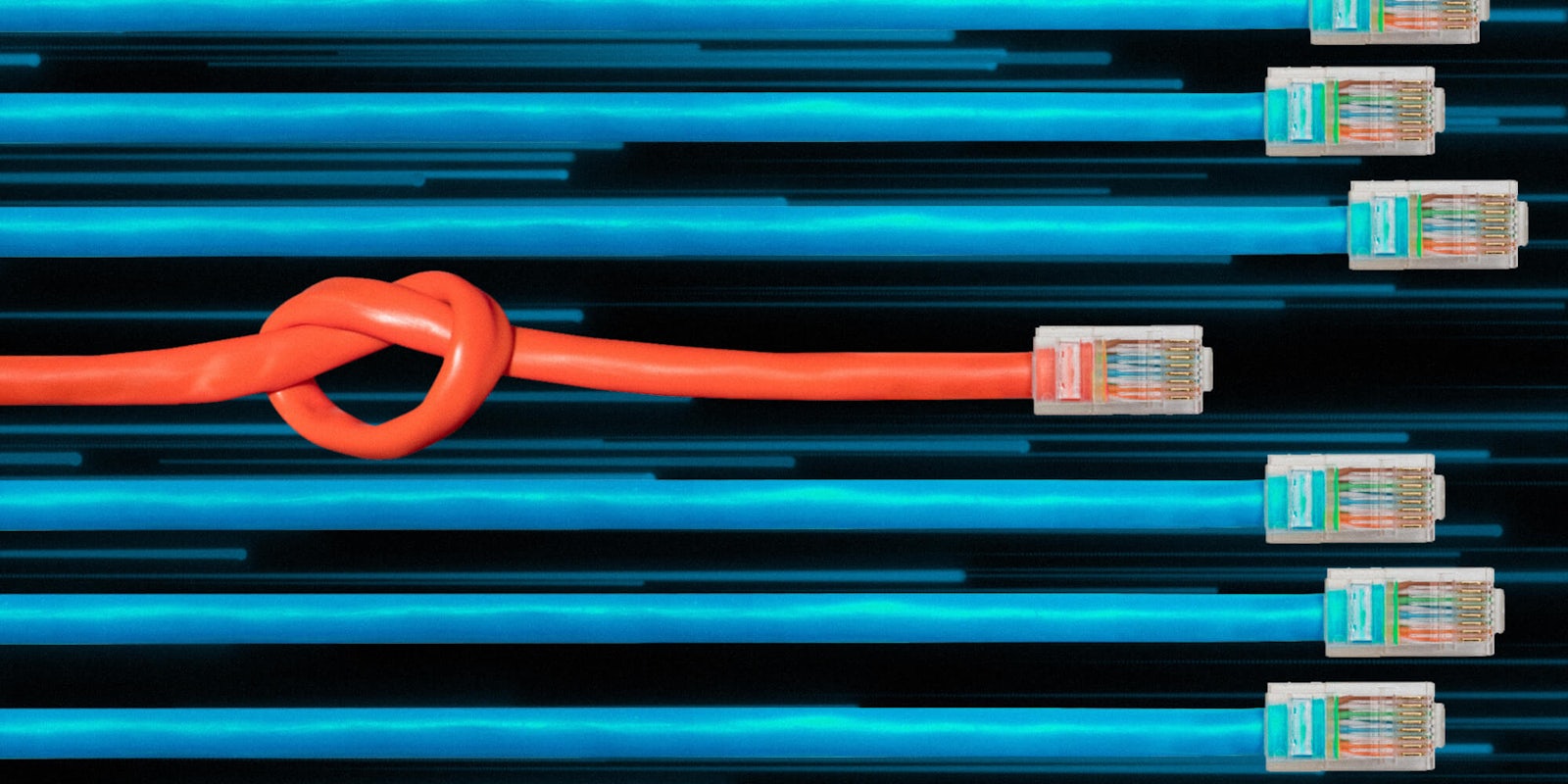

At it’s core, the arguments in favor of net neutrality rules center around nondiscrimination of content online.

While the “bright line” rules of not blocking, throttling, or having paid prioritization of content have generally received most of the attention in the debate, one issue, “zero-rating,” tends to get less.

The idea of zero-rating is fairly simple: an internet service provider (ISP) decides that certain services or content won’t count against data caps for a consumer.

However, that decision can be a slippery slope—as several advocacy groups have warned in the past and continue to do so as broadband policy makes its way into the political conversation.

Here’s everything you need to know about zero-rating, instances of zero-rating happening, and the criticisms of the practice.

What is zero rating?

Zero-rating is when an ISP does not count a specific app, suite of apps, or specific content against a consumers monthly data cap. Essentially, the practice makes certain data exempt, while other data would count against the cap.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation notes, oftentimes these zero-rating plans come from content providers who pay ISPs to apply the offering to their own content.

There have been several instances of ISPs offering products and services that don’t count against data caps (more on that later).

While on the surface such an arrangement may seem good for consumers, this set up creates a situation that could potentially lead to anti-competitiveness and an unfair playing field.

Many pro-net neutrality groups have voiced opposition to zero-rating plans for many of the same reasons they support open internet rules: to guard against the possibility of discrimination of content online.

Criticisms of zero-rating

Here’s an example of why zero-rating has raised alarms among digital rights groups:

Say internet provider XYZ launches a streaming service. They want their consumers to use that new service instead of Netflix and Hulu. To try and push that, they’ll make sure their streaming service won’t count against customers’ data caps, while Netflix and Hulu continue to do so.

It’s the same situation that has been envisioned by pro-net neutrality advocates with throttling of content and services.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, in 2017, said it “doesn’t flat-out oppose zero-rating” but that “it often has the consequence (intended or not) of giving ISPs unfair control over the content their customers access, and ultimately stifling competition.

When the ISP has sole control over what content sources are eligible for zero-rating, it becomes a de facto internet gatekeeper: its choices around free bandwidth can bias its customers’ internet usage toward certain sites and services. That can make it prohibitively difficult for new, innovative services to get off the ground. For example, entrepreneurs trying to promote a new video streaming site will face hurdles to widespread adoption of their service if users have unmetered access to existing competitors like YouTube and Netflix.

Similarly, Free Press’s Vice President of Policy and General Counsel Matt Wood said in 2016 that zero-rating give ISPs “the leverage to favor their own video products and services and dress up double-charging as a discount.”

More recently, a 2018 California net neutrality law that was hailed as the “gold standard” for states included zero-rating among other prohibitions like blocking, throttling, and paid prioritization. However, as the Verge noted at the time, the law does say that categories of apps—like all streaming apps—can be zero-rated, just not one specific app.

The law essentially makes zero-rating a level playing field if ISPs decide to use the practice.

The issue has even come up in presidential politics. During the 2020 primary, advocacy groups launched a petition for candidates to sign a pledge declaring they would restore net neutrality, reject telecom donations, and ban “harmful forms” of zero-rating.

As of late March, the petition had more than 230,000 signatures.

Instances of zero-rating apps

There have been several examples of ISPs deploying zero-rating tactics—and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) even pushed back against the issue right before net neutrality was repealed.

Most recently, a group of senators asked AT&T about exempting its new streaming service, HBO Max, from its customer’s data caps. AT&T told the Verge that the streaming service would be part of a “sponsored data” program where companies pay AT&T in order for services not to count toward data caps. Since HBO is owned by AT&T, HBO Max was essentially paying itself.

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), and Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) wrote a letter to AT&T in June, telling the company the zero-rating practice “appears to run contrary to the essential principle that in a free and open internet, service providers may not favor content in which they have a financial interest over competitors’ content.”

This isn’t the first time AT&T—and other ISPs—have been questioned about zero-rating practices.

The FCC wrote to major ISPs like AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, and T-Mobile in late 2015 essentially saying it was investigating whether their zero-rating services violated net neutrality rules.

The investigation ended after President Donald Trump’s administration ushered in a change of leadership at the agency, with current chairman Ajit Pai at the helm.

There are a number of other examples of zero-rating currently available.

T-Mobile’s “Binge On” service allows for people to watch a number of streaming services without it impacting their data caps.

Similarly, AT&T did not count DirectTV Now against its customer’s data cap.

In 2015, Comcast’s launched its own live streaming service that didn’t count against data caps, and in 2016 Verizon’s go90 service also didn’t count.

With the FCC dropping the investigations—thus showing a clear decision in thinking zero-rating is a fair practice—and net neutrality rules still repealed (which abdicated the agency’s authority over broadband) it’s likely you’ll see instances of zero-rating happening for the foreseeable future.

But as the net neutrality debate over the decades have shown: things change.

READ MORE: