In February, vlogger Myles Power was hit with multiple copyright infringement notices from YouTube threatening to delete his videos, take his pages offline, and bar him from publishing any new videos on the site.

His crime? Daring to critique a group of vitriolic AIDS denialists behind the misleading and inaccurate House of Numbers documentary.

With the help of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), Power’s videos have remained online, and Google, which owns YouTube, has issued a statement saying it will act “in accordance with law… [and] reinstate content in cases where there is clear fair use and we are confident that the material is not infringing.”

As a one-off, Power’s situation would be unremarkable. But that’s not the case. Hidden behind YouTube’s innocuous legalese is an irresponsible and potentially damaging copyright policy, one that is being systematically abused to silence criticism online.

Safe harbors

It was the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), enacted by the 105th United States Congress in 1998, that laid out the blueprint to how the distribution of copyrighted material is policed online. With the advent of the first websites that feature user-uploaded content, it became clear that new regulation was required, and website publishers could not be expected to be held criminally responsible for copyrighted material uploaded to their sites—so long as they did not encourage it and took reasonable steps to ensure its removal.

This exemption from prosecution or penalisation is known as “safe harbour” status. In order to be considered a “safe harbour,” a site must not have knowledge of the material, nor draw financial benefit from it (though in cases of ignorance, this becomes difficult to ascertain the truth of), and—crucially—must implement a takedown system that allows copyright holders to notify the site of infringing content.

None of this is controversial. That websites should take adequate precautions to ensure that they are not hosting copyrighted material illegally or provide rights holders with a system to notify them when copyright law is violated is not unreasonable.

Unfortunately, this is not what YouTube has done.

With more than 100 hours of video uploaded every hour to YouTube, it’s impossible for Google to adequately manage its own site content, and the system it has created for rights holders is full of loopholes that can be exploited by copyright holders and random users to take down videos.

Three strikes and you’re out!

YouTube functions using a three-strike policy. If a YouTuber’s account is flagged three times by rights holders as uploading unauthorised copyrighted material, and these complaints are upheld (there is an appeals process), then the account is shut down, and the user is permanently banned.

So what’s the problem? Don’t upload material without permission, don’t get banned. Surely that’s the end of the story? The issue is that Google’s shoot-first-ask-questions-later approach is ripe for abuse, and offers few real protections by way of fair use.

The vast majority of people who upload copyrighted material to YouTube (and other sharing sites) are not deliberate pirates, hosting films and albums in their entirety. Rather, they are sharing reviews, or parodies, or “transformative” reinterpretations, or myriad of other reuses that are unauthorised by the original rights holders but nonetheless protected under U.S. law by fair use.

Screenshot via YouTube Spotlight

YouTube certainly tries to adhere to the notion. Above is a screengrab from the company’s video primer on copyright law—as explained by Happy Tree Friends.

However, as YouTubers are finding again and again, YouTube’s policies are ripe for misuse, and they’re repeatedly abused by rights holders to take down videos despite clear fair use exemptions applying.

Endemic abuse

As we’ve seen, Myles Power risked having his account terminated for critiquing the dangerous AIDS denialist documentary House of Numbers, because in doing so, he included some clips of the documentary.

Due to the nature of YouTube’s DMCA notice system, the burden of proof falls on Power to prove himself not guilty, lest he lose his account and be banned from ever posting videos again. This is despite the fact that Google considers Power such an asset to the YouTube community it’s previously flown him across the Atlantic to take part in its “EDU guru” campaign.

Power’s experience is just the latest in a sorry stream of DMCA takedowns that are extremely tenuous and, when taken together, make a mockery of YouTube’s copyright policies. To give just a few examples:

- Back in 2007, Universal Music Group issued a DMCA takedown request against conservative video blogger Michele Malkin. She had had made a video podcast criticising Akon, including clips of him in the process. Universal proceeded with the takedown despite Malkin’s video quite clearly falling under the fair use exceptions, and with the EFF’s help, she managed to get her work reinstated. “It is impermissible and irresponsible for copyright holders to use the DMCA as a pretext to squelch criticism,” the EFF said in a statement. “Criticism and commentary are not only at the core of fair use, but vital to our traditions of free speech.”

- A 15-year old Australian boy was able to have more than 200 clips from TV show The Chaser’s War On Everything taken down from YouTube in 2007 by pretending to represent the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). The requests fly in the face of ABC’s content sharing policy of “get[ting] our content out there on as many platforms as possible,” but the website nonetheless immediately complied with the takedown requests, making no attempt to verify who the boy was before acting upon them.

- Prince’s lawyers in 2008 had dozens of fan videos of his Coachella cover of Radiohead’s “Creep” taken down in 2008. The only problem is—because it’s a cover—Prince has no rights to the song whatsoever. They remain with Radiohead, who immediately sought to have it unblocked: “it’s our song,” the band countered. Critics have accused Prince of having an “overzealous campaign to control all uses of work attached to his name, even at the cost of preventing legitimate fair uses.” YouTube’s policies are potentially making it easier for him to do so.

- In 2011, Universal had London grime artist Skepta’s new track taken down in a clear-cut, flagrant abuse of the system. Universal had no claim to Skepta’s song whatsoever. It simply wanted to license it for an Eminem song and didn’t want people associating the track with anyone else (in this case, the original artist and legitimate rights holder).

- Sega used the DMCA takedown system in 2012 to launch an assault on any and all footage of Shining Force, a 15-year-old Sega Megadrive game with a limited release outside of Japan. The assorted “Let’s Play” videos, reviews, and nostalgic retrospectives were allegedly targeted to avoid them “cluttering up” search results ahead of the launch of PSP title Shining Ark. Several channels were shut down as a result of these dubious DMCA notices, with some affected allegedly containing no in-game footage whatsoever.

- Colorado political hopeful Gordon Klingenschmitt abused the system last year to repeatedly take his critics’ YouTube channels offline, launching bogus DMCA notices the moment his opponents’ channels were found to be non-infringing in order to take them down once again. How did he manage this? Because YouTube has set the bar so low for the evidence required to back up DMCA notices that it might as well not exist.

- Last October, professional video games reviewer John Bain (a.k.a. TotalBiscuit) found himself on the receiving end of a DMCA takedown after posting a negative review of Day One: Garry’s Incident on his YouTube channel. That he had included clips of the game in the review was apparently sufficient grounds for a takedown notice to be served to him.

A climate of fear

It’s important to stress that reviewing games is TotalBiscuit’s livelihood. On YouTube, video views generate ad revenue, and these days top YouTube stars can easily pull in six-figure incomes.

As such, these rogue takedown requests could have a chilling effect on the professional review industry, and customers will suffer as a result. As TotalBiscuit points out, “critique makes this industry better,” and YouTube is now considered an authoritative source for information on new games and media, the first port of call for many video games fans searching for information on what to buy. When professional critics are threatened with losing their revenue stream simply for posting a bad review, who can blame them for shying away from controversial or just plain bad games? In turn, the consumers coming to YouTube for unbiased information could get an incomplete and misleading picture.

“Unless YouTube can protect its content partners from this kind of attack,” TotalBiscuit concludes, “the kind of people they want producing content for the site will be far too afraid of making it.”

As a business, YouTube’s interests are ultimately not synonymous with those of its community.

Yes, the appeal system is there if you believe your video falls under fair use exemptions, but it’s time-intensive and arguably ineffective. What’s worse, the process freezes earnings from AdSense, Google’s equally flawed revenue-sharing service.

While YouTube warns of “legal consequences” for submitting false claims, I found no evidence of anyone or any organisation significantly penalised at any point for submitting wilfully false claims. Those accused, meanwhile, are effectively guilty until proven innocent, even if no evidence as to their guilt is provided by the accuser.

The reason is simple: As a business, YouTube’s interests are ultimately not synonymous with those of its community. It has to protect its own interests and minimize potential legal concerns.

For a case in point as to the ferocity of many rights holders, look at the recent bizarre case concerning German royalty group GEMA. Having successfully forced Google to implement tools to block music that they hold the rights to, GEMA is once again taking Google to court—claiming the block messages shown in place of the videos “misrepresent the situation and damage GEMA’s reputation.”

When approached for comment, a YouTube spokesperson issued the following statement:

“When a copyright holder notifies us of a video that infringes their copyright, we remove the copyright promptly, as required by the DMCA. The DMCA also provides for a counter-notification process if a user believes a content owner has misidentified their video, and we reinstate content when the user prevails in that process. We also reinstate content in cases where we are confident that the content is not infringing.”

With the constant threat of legal action hanging overhead, it’s possible to understand—though not justify—Google’s rationale in implementing such restrictive policies.

Who’s really innocent?

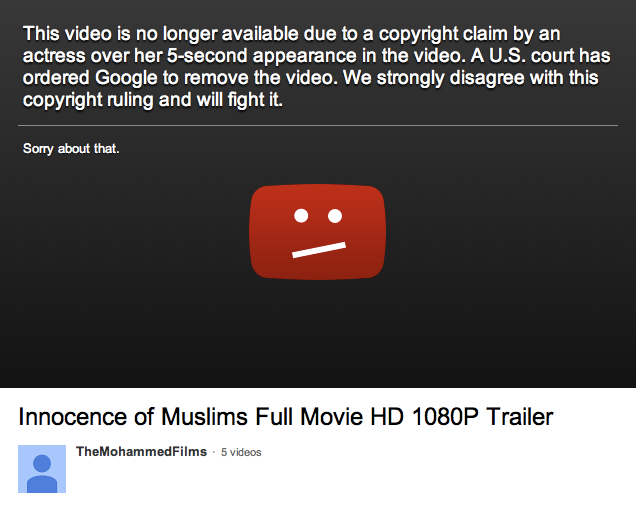

Now, however, the tables have turned slightly on YouTube. Unhappy with her five-second appearance in controversial anti-Muslim film Innocence of Muslims, actress Cindy Garcia took Google to court to have the video removed from YouTube—and won. Clearly bitter, Google swapped out the standard DMCA replacement message on the video with one of its own:

Screenshot via TheMohammedFilms/YouTube

Unfortunately, the hypocrisy of fighting so hard for “freedom of speech” while simultaneously upholding policies that are demonstrably curtailing it is sadly lost on Google.

Illustration by Rob Price