Last football season, Yahoo‘s Darren Burton did something he’d never done before: he commissioned a fantasy football league. That may not sound like a particularly impressive feat to you, but for Burton, navigating lists of players, stats, and scores is a unique challenge, because he is blind.

Burton is an accessibility specialist on Yahoo’s accessibility team, a four-man group of engineers and designers that make Yahoo’s family of apps accessible for everyone, including those with visual, audio, or physical impairments. So when Yahoo began making its fantasy service, full of numbers and real-time feeds, fully accessible to everyone, Burton didn’t want to just test it; he wanted to be the boss.

I briefly met Burton at Yahoo’s accessibility lab, a large room at the company’s Sunnyvale, Calif. headquarters where everyone from Yahoo employees to new graduates to startup founders to CEOs of international companies can peek inside the inner workings of Yahoo’s accessibility efforts and discover ways to improve their own services.

According to the World Health Organization, more than one billion people have some form of disability today. That’s one in seven people around the world who may look at technology as a way to make their lives more manageable.

Although companies are required by law to make their apps and services accessible to people with disabilities, it’s still widely overlooked, especially among early-stage companies who are trying to build and grow quickly. By taking a look at their apps at Yahoo’s lab, designers and engineers can see the holes in design and functionality that are limiting to people with physical or mental impairments.

As Mike Shebanek, senior director of Yahoo’s accessibility team explained, all new employees–or “Yahoos” for short–must go through an accessibility training workshop that includes a handful of slides and hands-on testing with gear the team has around the office. When he asks recent college graduates about how much they learned about making tech accessible in university programs, the answer is always the same: Nothing.

“You can come in with a computer science degree, an engineering degree, a software design degree, you probably won’t have heard of accessibility,” he said. “People are coming to work in this field not realizing the need to do this work, and how to do this work.”

In the lab, goggles, gloves, and screen readers show people what it’s like to use services with visual, audio, or physical impairments. For instance, I wore goggles to simulate color-blindness and viewed ads for clothing I thought was a completely different color than it truly was; leather gloves with the fingers sewn shut demonstrated in a very low-tech way what it’s like to use a computer with limited hand movement, like arthritis or missing digits.

I went through the same hour-long training new Yahoos go through, that included a presentation slide with the infamous “dress,” underscoring that the way people view and use technology is never quite as obvious as you think. The lab itself was somewhat underwhelming—not because accessibility isn’t important or interesting, but because making apps and services accessible means getting a lot of inconspicuous things right.

Shebanek’s experience in assistive tech spans decades, and he is partially responsible for what could be considered the best accessible tech out there—he was part of the team that built VoiceOver for the Mac, and then later the iPhone, at Apple.

“When personal computers came out, they didn’t have a lot of assistive technology. You had to go to a specialized company that provided specialized software training and it cost a lot of money to add this to the computer,” he said. “When mobile came along, it learned from that, and the big change was it now got integrated. Starting with the iPhone 3GS, and now Android, the assistive technology you used to have to get separately is just in there.”

Apple is widely regarded as one of the leaders in accessible technology. The American Foundation for the Blind awarded Apple the Helen Keller Achievement Award in 2015 for “breakthroughs in accessible technology.” And the company’s VoiceOver feature makes many apps automatically accessible to people with vision or other impairments.

However, developers have to build functionality into their apps; adding alt-text for VoiceOver will make it so the text doesn’t consist of repetitious commands. Alt-text is invisible captioning that screen readers dictate to the user when using different services.

In order for screen readers to know what each button or feature in an application does, developers must add text within the code that explains it. For instance, in the Yahoo Video Guide app, buttons for ratings, reviews, trailers, and GIF selection must be labeled. In the app, people can choose to watch movies based on “mood,” and engineers had to define what each GIF mood represented.

As Shebanek took me through demonstrations of the apps, there were some lingering issues. In the Video Guide app, for instance, the star, which a sighted person would recognize as “favorite” was read aloud as “button.” And even the Fantasy app had some minor hiccups when viewing player statistics.

Along with its family of apps including Fantasy Sports and Yahoo Esports, Yahoo, a struggling tech behemoth trying new ways to stay relevant, is improving video accessibility. It’s the first company to automatically add closed captioning to movie trailers and video produced by the New York Times, Shebanek said.

Many people are somewhat familiar with tech for the visually impaired, but there are numerous disabilities developers and designers must consider when building products. In order to raise awareness and help people in tech make products that appeal to diverse audiences, Global Accessibility Awareness Day on May 19 provides resources and promotes events and workshops around the world to get people thinking about technical inclusion.

An industry-wide effort

With the saturation of mobile, it’s becoming easier to make apps accessible to everyone, and the technology automatically lends itself to assisting those with physical or mental impairments. Tablets are popular for people with learning disabilities, and for some people with disorders like autism, iPads have become crucial communication tools.

Earlier this year, Apple launched a campaign coinciding with Autism Acceptance Month to raise awareness about autism and demonstrate the unique ways people are using iPads to communicate and learn. Two videos feature Dillan, an autistic student who uses his iPad to give him a “voice;” he even used it to speak at his middle school graduation.

Facebook, too, is innovating on mobile, and is perhaps further along with implementing accessible photos on a large scale than any other company.

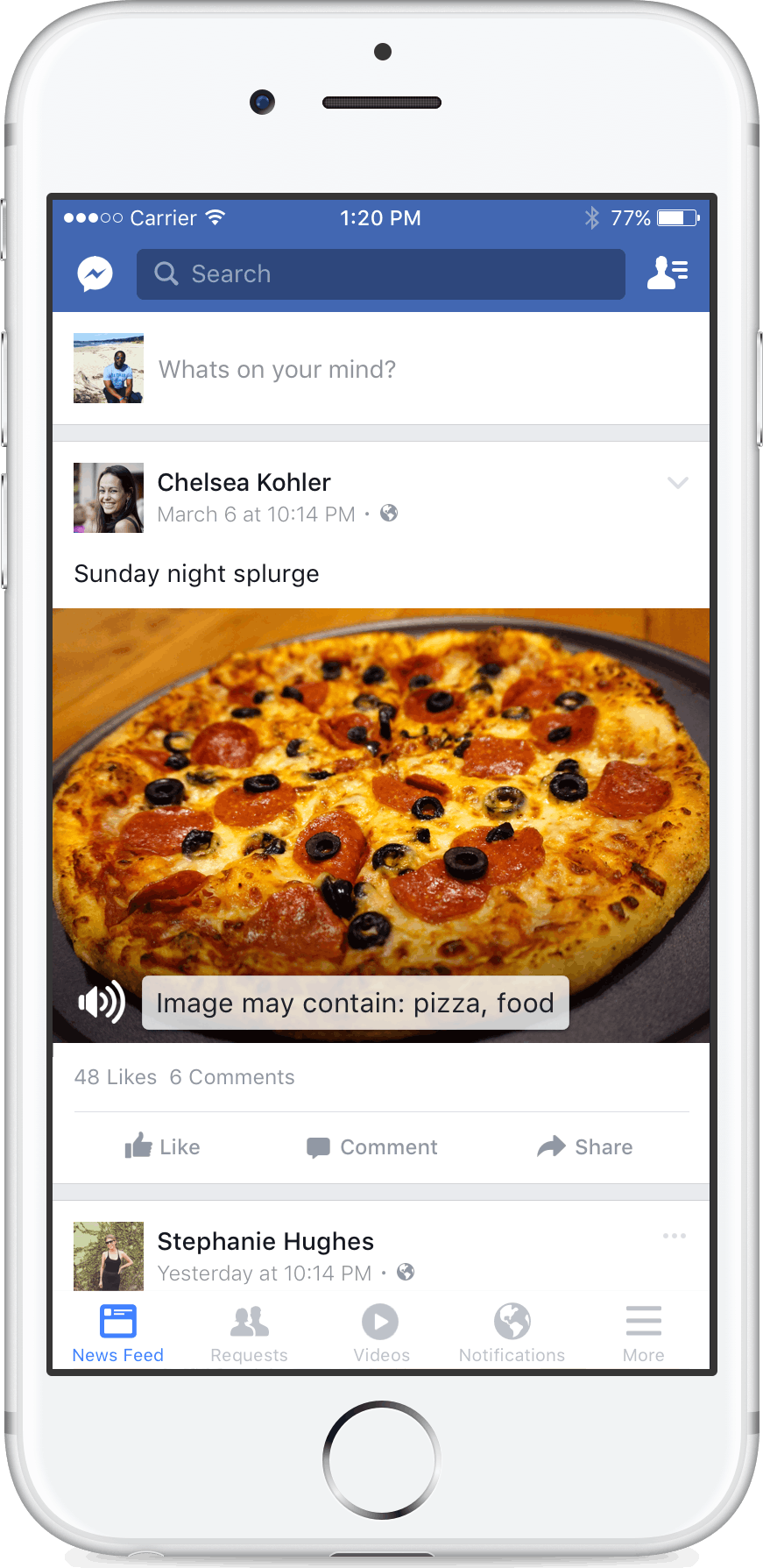

In April, Facebook launched automatic alt-text for iOS, software to recognize objects and scenes in photos and automatically caption them.

Now, when a visually-impaired individual is scrolling through their Facebook feed, the app will describe what photos could be, even without the help of friends captioning them. Screen readers might say something like: “This photo may contain a dog.”

Facebook trained its object recognition technology on millions of examples uploaded to Facebook and its suite of apps. Previously, screen readers would only be able to read the caption that a user provided. The company also uses facial and object recognition technology in its Moments app, tag suggestions, and is improving its artificial intelligence tools to improve photo search and object recognition.

“Automatic alternative text is the first step and focuses on object recognition, but in time we hope to include other technology like facial recognition, so that blind people have the same experience on Facebook that sighted people do,” Matt King, accessibility specialist at Facebook said in an email interview.

“Our goal isn’t to generate extremely long and detailed descriptions, but instead to provide enough of a description to enable blind users to ask the system for the additional details that they would like. We envision that some day, we’ll have developed a way for people to ‘interrogate’ photos in order to derive the information they believe most important.”

Facebook is currently limiting the number of concepts it recognizes to 100, so a sighted person scrolling through Facebook with VoiceOver activated might not feel as if the captions are very descriptive. But for someone with a visual impairment, it’s a huge improvement. The company plans to add more concepts over time. In an email, King shared some of the concepts the software currently recognizes:

Here are some of the concepts that can be identified by our system:

- Transportation words: Car, Boat, Airplane, Bicycle, Train, Road, Motorcycle, Bus

- Nature words: Outdoor, Mountain, Tree, Snow, Sky, Ocean, Water, Beach, Wave, Sun, Grass

- Sports words: Tennis, Swimming, Stadium, Basketball, Baseball, Golf

- Food words: Ice Cream, Sushi, Pizza, Dessert, Coffee

- Words that help describe someone’s appearance: Baby, Eyeglasses, Beard, Smiling, Jewelry, Shoes

- And, of course, Selfie!

Twitter is also making strides to better serve its visually impaired users. The company rolled out alt-text options for photos in March, letting users add their own alt-text to images so anyone can enjoy photos.

Progress on mobile is moving much faster than its personal computing predecessors, but as more platforms begin to crop up, developers and designers must begin thinking about how to make them accessible when there’s no real foundation or expectation yet.

The leapfrog from PCs to mobile was relatively straightforward, and people are still using things like Braille displays to pair with phones, mini versions of those for computers. But how do you make virtual reality, for example, accessible to someone who can’t see?

To help answer these kinds of questions and inspire the next generation of developers to build inclusive apps by default, Yahoo and partners from Google, Twitter, Microsoft, LinkedIn, Facebook, and other tech companies joined universities and nonprofits to create Teach Access, a group that aims to incorporate accessibility education into the classroom, and make these concepts mainstream. Yahoo hosted the kickoff meeting in April.

“While universities are creating experts, and experts help move forward, it’s the rank and file that do all the work. They’re coming in knowing nothing. How do we get to those people? How do we make this general knowledge?” Shebanek asked. The group compiled information and the basic key concepts and skills that are needed by average tech workers, and is now trying to figure out how to help universities implement it in their curriculum.

These companies are at the forefront of accessibility technology, and while the industry as a whole is still learning the ins and outs of what truly makes a product or platform “for everyone,” the fact that these questions are being asked means that eventually the solutions will be standard.