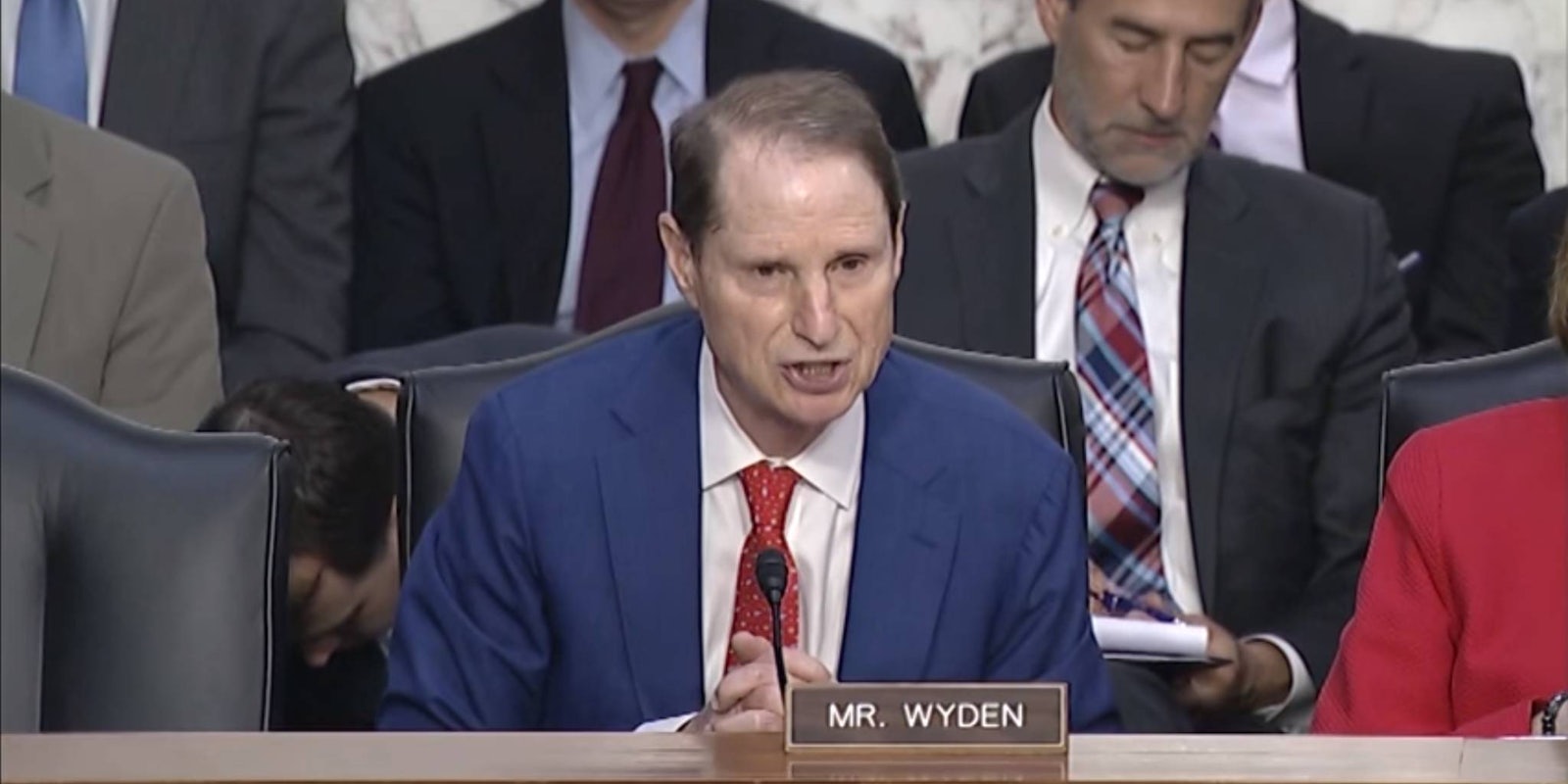

The head of the CIA and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) locked horns at a congressional hearing Thursday in a debate over the future of strong encryption in the United States and around the world.

Wyden and John Brennan, director of the Central Intelligence Agency, had a particularly vigorous disagreement over whether the U.S. was even capable of banning strong encryption given how global the technology has become.

“First of all, U.S. companies dominate the international market as far as encryption technologies that are available through these various apps and I think we will continue to dominate them,” Brennan said. He further argued that the idea that foreign companies could provide the same capabilities was “theoretical.”

Encryption has been a point of debate in the U.S. for several years, especially after Apple made it a default option to protect files on iPhones. It flared up following the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack when the technology, which scrambles computer code so effectively that only authorized users can access it, prevented the Federal Bureau of Investigation from opening the phone of one of the shooters.

However, encryption is widely used to protect everyday internet use, including ecommerce, messaging, and more. The technology is seen as crucial to protecting the cybersecurity of the American government, the country’s businesses, and individuals.

A vast consensus of technologists argue that requiring special access to encrypted technologies, known as “backdoors,” for the U.S. government would ultimately weaken the cybersecurity of Americans overall against hostile governments and other malicious actors.

A 2016 Harvard study also strongly disagrees with Brennan, concluding that America cannot ban effectively ban strong encryption and require backdoors because the technology is ultimately a global phenomenon.

“It is clearly inaccurate to say that foreign encryption is a ‘theoretical’ capability,” Wyden said in a follow up statement on Thursday. “Strong encryption technologies are available from foreign sources today—half of them of them are inexpensive and the other half are free. U.S. tech companies dominate this field today, but they are competing in a global marketplace. These products are used by consumers and businesses every single day to protect everything from bank records and business transactions to personal communications and other sensitive data.”

Wyden argued that requiring American companies to include backdoors for U.S government and law enforcement “would not stop terrorists from using strong encryption and it would undermine American competitiveness and Americans’ digital security at a time when the threat from foreign hackers and cyberattacks has never been greater.”

The Harvard study, titled “A Worldwide Survey of Encryption Products,” pointed to numerous technology companies that moved outside of the U.S. to avoid government interference as well as open-source software that is “jurisdictionally agile” and more capable of moving to countries, like the Netherlands, that have rejected backdoors.

International encryption products are on par with American technology, the study found, further undercutting the idea that the U.S. government could unilaterally force backdoors and effectively shut down strong encryption that places data beyond their reach.

“If U.S. products are all backdoored by law,” Bruce Schneier, Harvard researcher and an author on the report, told the Daily Dot, “I guarantee you stuff coming out of Finland is going to make a big deal of that.”