Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a fairly obscure—yet vitally important—law that has shaped the modern internet has suddenly been thrust into the political spotlight in recent months.

The law has been brought up by both 2020 presidential candidates, has been at the center of an executive order, and is a target in a number of bills in Congress. But tech advocates have warned that changing the law could have far-reaching consequences.

So what is Section 230 and why has it suddenly become one of the more hotly debated parts of tech policy in recent months?

What is Section 230?

Section 230 is part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. It was written by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and former Rep. Chris Cox (R-Calif.).

The section acts as a liability shield for all websites. Essentially, it shields websites from being held responsible for the content posted on it by its users.

The law is the reason comment sections on websites and forums can be robust, but it also is the reason users can upload their own videos to YouTube, or write reviews on Yelp, or post what they want on Twitter. There are some carveouts for egregious content.

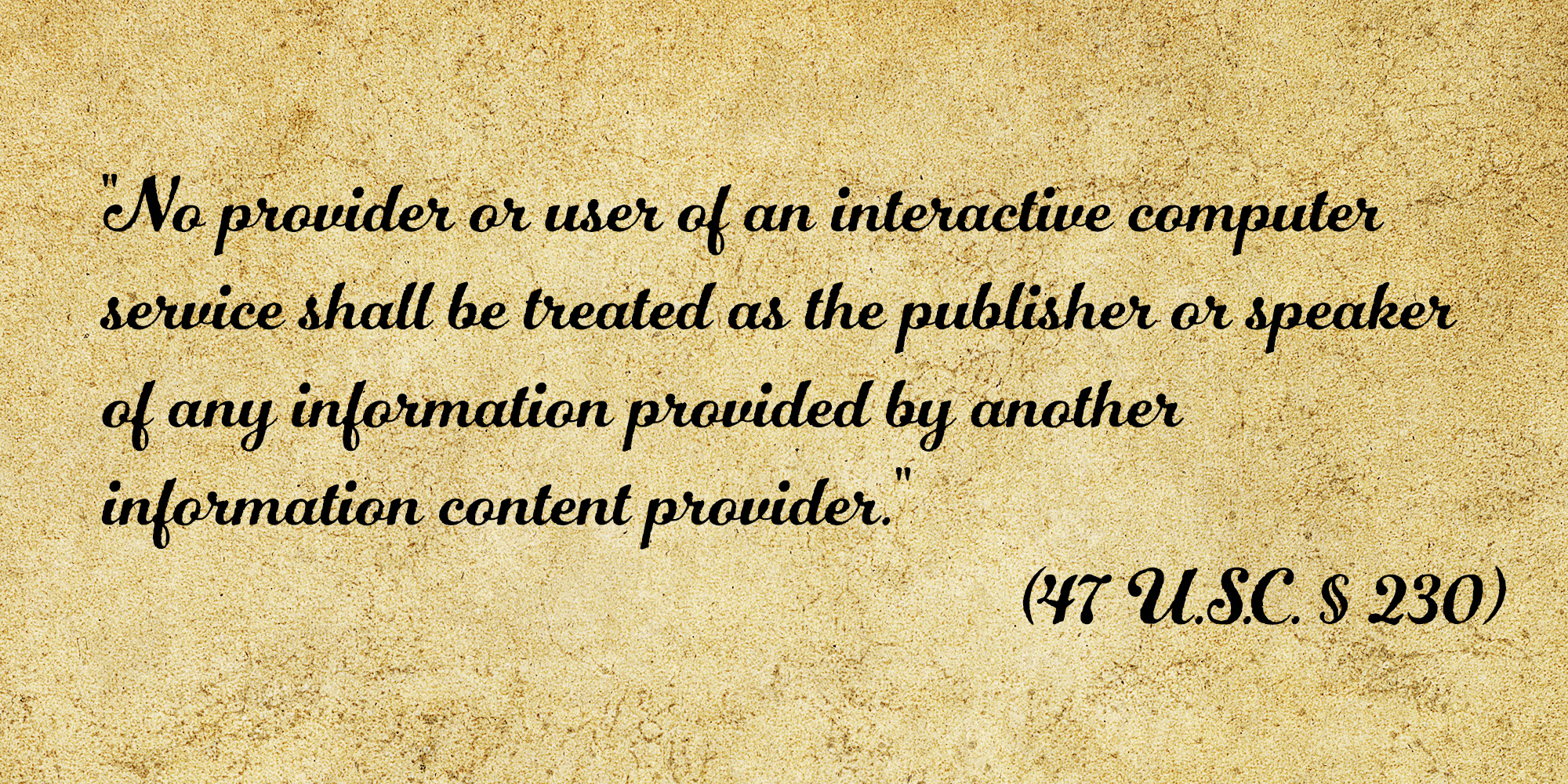

It specifically says:

"No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider."

It continues:

"No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of— (A) any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected; or (B) any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in paragraph."

That protection allows websites to host content uploaded by their users without fear of being held liable for what that content is. Without it, it's likely a website wouldn't host content, fearing that there was a possibility it could open itself up to massive lawsuits.

The section has a lot of backers, despite the recent criticisms from both sides of the aisle. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) calls it "one of the most valuable tools for protecting freedom of expression and innovation on the Internet."

Meanwhile, Jeff Kosseff, an assistant professor of cybersecurity law at the U.S. Naval Academy, named his book about the law The Twenty-Six Words That Created The Internet.

Kosseff spoke with CNN in May about the law and summed it up.

"What those words mean is basically that any online platform— whether its social media, a website, Wikipedia, Yelp—they are responsible for any content that they create. But unless one a few limited exceptions apply, they are not responsible for any posts, any videos, any images that their users post on the site," Kosseff said.

Who wants to change Section 230?

A laundry list of lawmakers seeking to change Section 230 runs from Congress all the way to the presidential level of politics.

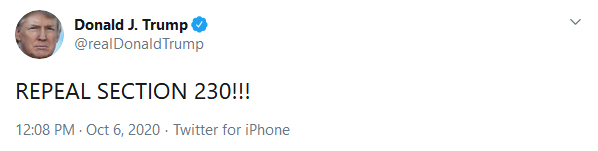

Both President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden have spoke about repealing, or revoking, Section 230.

Trump has already made moves to change the law. In May, the president signed a social media executive order that directed the executive branch to petition the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to "clarify the provisions" of Section 230.

The FCC accepted the petition for rulemaking and recently wrapped up collecting public comments on the issue. The comments prompted a wave of posts from both people who supported Trump's order and those who were fiercely opposed.

For instance, Reddit told the FCC that changes to the law would "change the very trajectory of the internet."

Trump's order makes it clear that it is in response to a perceived anti-conservative bias by social media companies, as it was signed shortly after his tweets were fact-checked.

Meanwhile, Biden's gripe with Section 230 seems to be about misinformation on platforms like Facebook, a company that he has taken direct aim at on the campaign trail.

The former vice president spoke with the New York Times in January and specifically said that Section 230 should be "revoked."

“It should be revoked because [Facebook] is not merely an internet company. It is propagating falsehoods they know to be false, and we should be setting standards not unlike the Europeans are doing relative to privacy,” Biden told the Times. “You guys still have editors. I’m sitting with them. Not a joke. There is no editorial impact at all on Facebook. None. None whatsoever. It’s irresponsible. It’s totally irresponsible.”

But its not just Trump and Biden who have expressed interest in using Section 230 as a crux for social media and big tech gripes. Congress has introduced 17 bills about the law this year as of early October, according to Tech Dirt.

The array of bills range from ones that have attracted a lot of controversy and chatter like the "EARN IT Act" to lesser known ones like the "Don’t Push My Buttons Act" which was introduced by Sen. John Kennedy (R-L.A.) in the Senate, and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii) and Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Arz.) in the House of Representatives.

Meanwhile, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) has called the section a "gift" for tech giants and that they were not "treating it with the respect that it deserves."

Unlike Trump and Biden, who have suggested repealing or revoking, the laws in Congress are largely focused on changing, poking holes in the law, or using it as a provision that's granted in return for doing something else.

Outside of Congress, the Justice Department and Attorney General William Barr have also advocated for Section 230 changes and even have offered Congress legislative framework for changes that it would like to see happen.

It seems (almost) everyone in Washington D.C. wants to meddle with Section 230.

Changing the law could have big consequences

But tech advocates have warned that changing Section 230 could have big implications.

For Trump, Section 230 has actually allowed him to post some of his more incendiary tweets.

In late May, Tim Wu, who coined the term net neutrality, pointed out that without the section's protections, Twitter would likely have been forced to take down some of Trump's "many defamatory posts."

"The White House doesn’t seem to realize that if they succeeded – if Twitter was actually liable for the speech of its users (if 230 was repealed) – they’d be forced to take down the many defamatory posts of Donald Trump — Section 230 is actually his best friend,” Wu tweeted.

The ACLU also pointed out that irony shortly after Trump signed the order.

"Ironically, Donald Trump is a big beneficiary of Section 230. If platforms were not immune under the law, then they would not risk the legal liability that could come with hosting Trump’s lies, defamation, and threats,” the organization tweeted.

But the implications go far beyond Trump's ability to use the internet. Changes to Section 230 would effect pretty much every internet user.

Reddit, in its public comment to the FCC opposing Trump's social media order, noted that changes to the law would threaten individual moderators of the site's subreddits to being open to liability.

"It is our view that the debate on Section 230 too often focuses solely on very large, centrally moderated platforms—and individual grievances with them—to the exclusion of smaller, differently organized websites that take an alternative approach," Reddit’s comment reads, adding: "However, the most important point that we offer, as we hope to make clear in this filing, is that with regard to Reddit and other community-moderated websites, Section 230 protects our individual users just as much as it does us. Their continued protection is crucial to the viability of community-based moderation online."

That kind of threat of liability would trickle down across the internet, some have argued.

The Center for Democracy and Technology, a 501(c)(3) that sued the Trump administration over his social media executive order, told the Daily Dot last month that if Section 230 was revoked, it would "lead many services to simply shut down."

"It would also make those remaining services less willing to remove objectionable content for fear that they would end up in litigation over that decision—the original Moderator’s Dilemma that Section 230 was designed to solve," Emma Llansó, the director of the Free Expression Project at the Center for Democracy & Technology, said. "An online ecosystem that features more concentration of power and less responsiveness to abusive content is not a world that any politician should endorse."

Despite the potential wide-spreading ramifications, Washington, D.C. seems dead set on changing this important internet law.