Anyone upset with the current state of politics has almost certainly complained about gerrymandering to you.

They’re not alone. Even former President Barack Obama called for the end of gerrymandering during a State of the Union speech. However, people fighting for more parity in districts just faced three major setback.

Several major cases that aimed to redefine political gerrymandering were punted by the Supreme Court in June, leaving the future of the controversial practice up-in-the air.

In mid-June, the Supreme Court dodged two cases, which argued against a Wisconsin redistricting map that they believed was a partisan gerrymander and a Maryland district Republicans disliked.

On June 25, the Supreme Court sent a case that centered around Republicans drawn congressional maps in North Carolina back to a lower court, the third decision in the past month that dodged the matter.

The lower court will decide whether those who brought the lawsuit have legal standing, the Washington Post reports.

At the same time, the Supreme Court ruled in Abbott v. Perez that three of four challenged districts in Texas were OK, but called one an “impermissible racial gerrymander,” BuzzFeed News reports. The lower court’s ruling, which had found the districts to be gerrymandered, relied too much on a “taint” from maps passed in 2011, according to Alito.

That case passed 5-4, with a dissent from Sonia Sotomayor, who wrote in her dissent that the districts were a direct attack on American democracy.

[This ruling] means that, after years of litigation and undeniable proof of intentional discrimination, minority voters in Texas—despite constituting a majority of the population within the State—will continue to be underrepresented in the political process. Those voters must return to the polls in 2018 and 2020 with the knowledge that their ability to exercise meaningfully their right to vote has been burdened by the manipulation of district lines specifically designed to target their communities and minimize their political will.

The Wisconsin case, Gill v. Whitford, was deemed to lack standing by the Supreme Court, according to reports. However, the Supreme Court found that they could continue arguing their cases in lower courts in the state.

Supreme Court dismisses Wisconsin partisan gerrymandering case for lack of standing

— SCOTUSblog (@SCOTUSblog) June 18, 2018

The plaintiffs in the case argued that Republicans drew a map that violated their constitutional rights. A decision by the Supreme Court was seen as a way to set limits on partisan gerrymandering. In another case, Benisek v. Lamone, the Supreme Court said a court’s ruling to not force a map to be redrawn was correct.

In Maryland partisan gerrymandering case, Supreme Court holds that district court did not abuse its discretion in denying preliminary injunction in this case, without deciding any questions on the merits

— SCOTUSblog (@SCOTUSblog) June 18, 2018

In the North Carolina case, Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court also asked the lower court to review if the plaintiffs had the proper standing to bring the case.

Here’s everything you need to know about gerrymandering.

What is gerrymandering?

Gerrymandering starts with the drawing of political districts—designated areas of voters—across the United States. Each member of the House of Representatives represents a single congressional district.

The number of representatives elected per state is based on the Census count of the state’s population. The idea seems simple enough—until partisan politics become involved.

The next census is scheduled to take place in 2020 under President Donald Trump’s watch. The process has already been criticized as being political, as the budget for the U.S. Census was slashed by the current administration. Critics fear this will lead to undercounting of communities of color, skewing the numbers that will be used when it comes time to reexamine political districts across the country.

Trump’s pick to lead the 2020 Census, Thomas Brunell, has no government experience and wrote a book that argued that competitive elections were bad for the country. In the book, he argued that the United States should “pack” districts with as many like-minded partisan voters as possible.

Gerrymandering is essentially a particular political party drawing district lines in a way that benefits their own party. State legislatures are generally in charge of creating the boundaries, but that is not always the case. More on that later.

How long has this been going on?

The term “gerrymandering” is nothing new. It’s named after Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who in 1810 redrew districts in Massachusetts to favor his own party. The term was added to Webster’s Dictionary in 1864, according to Smithsonian.com.

Why does gerrymandering matter?

Gerrymandering has very real political consequences. For instance, take the upcoming 2018 midterm elections.

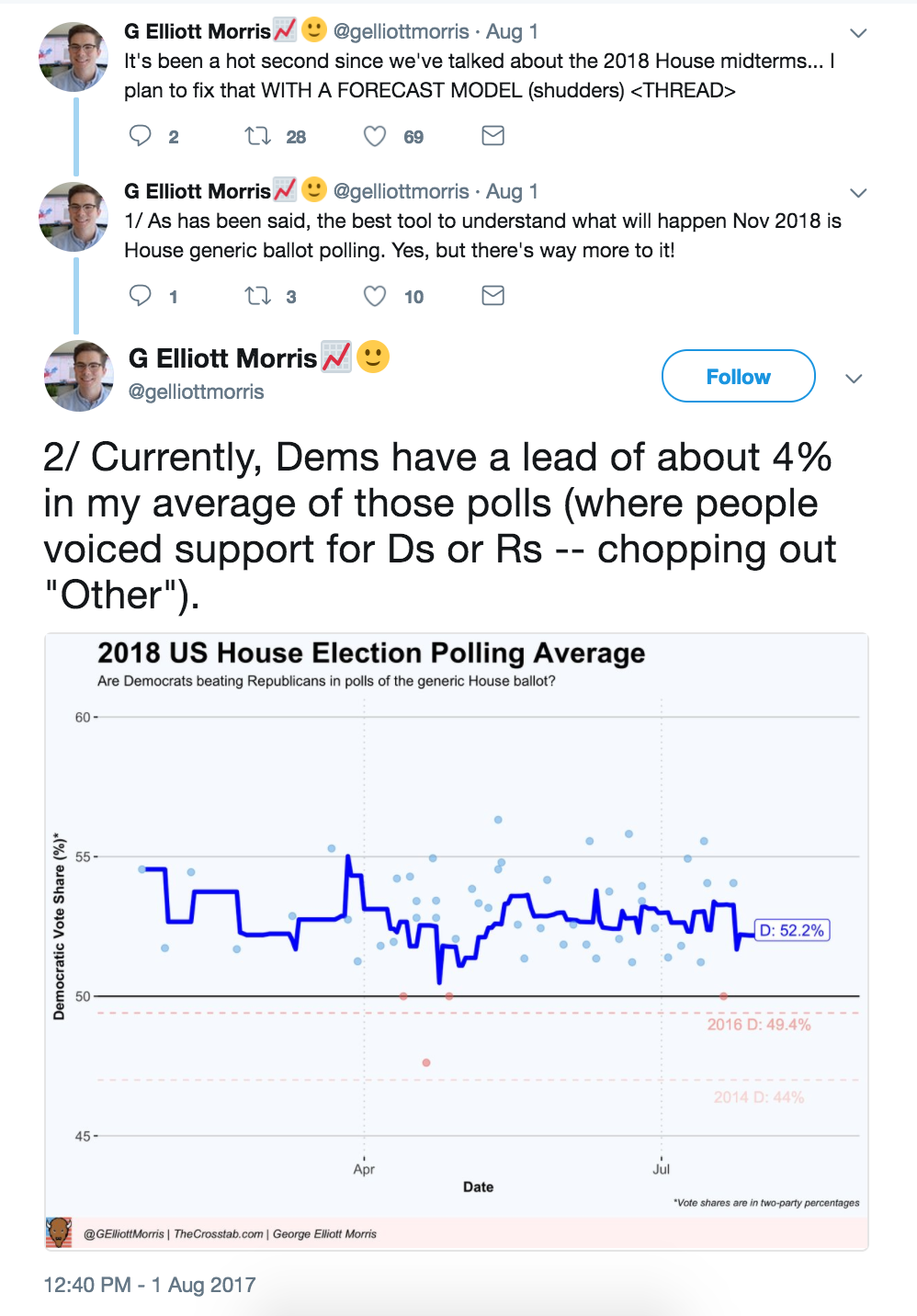

Decision Desk HQ released a forecast for how the 2018 midterm elections might shape out for the House of Representatives, where all 435 congressional districts are up for grabs.

Trend lines are currently projecting Democrats to get more votes in the midterms than Republicans due to plummeting poll numbers for both President Donald Trump and Congress as a whole, which is currently controlled by Republicans.

One estimate by the Brennan Center for Justice found that 16 or 17 current Republican seats in the House of Representatives are believed to be the result of gerrymandering. However, both major political parties have used the practice to their advantage in the past.

READ MORE:

- Trump impeachment: Here are the odds Trump leaves office early

- Who’s going to challenge Trump in 2020? Here are 9 super-early contenders

- Untangling antifa, the controversial protest group at war with the alt-right

As Decision Desk HQ points out, however, the gerrymandered districts across the United States would result in Democrats receiving 54 percent of the total vote, but only 206 seats in the House, compared to Republicans, who would gain 229 seats with less than half of the overall vote.

While it’s difficult to blame all of this on gerrymandering—Democrats tend to live in clusters, or large urban centers, which leaves other districts open to Republican lawmakers—it certainly has a hand in creating a situation where the majority of the nation votes one way, but a different result ends up in Congress.

What are some of the more brazen examples of gerrymandering?

There are quite a few districts in the United States that you’d be hard-pressed to figure out how they came to be.

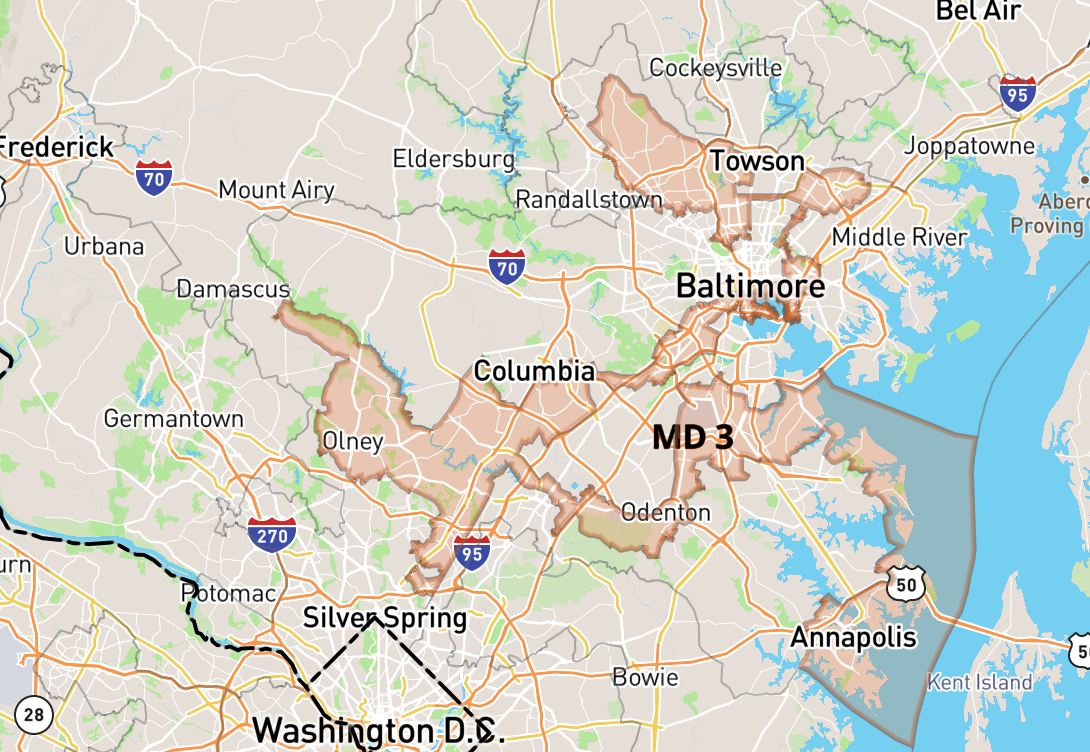

For example, Maryland’s districts, which were drawn by Democrats, are quite wild. Maryland’s 3rd Congressional District snakes along the state’s coast, into the heart of the state and even stretches into the northern part of the state, sometimes with small areas of land linking them together. It roughly looks like a backward “S.”

Meanwhile, North Carolina’s districts, drawn by Republicans, were equally as egregious. However, the Supreme Court struck down districts in the state, arguing that lawmakers violated the Constitution by relying on race to draw the districts. Similar cases have occurred in Alabama and Virginia.

The Supreme Court made two major decisions in June to sidestep political gerrymandering. In October, it heard arguments in Gill v. Whitford, a case that argued Republicans in Wisconsin drew politically charged district maps.

The Court decided against ruling on the case, saying that the whole state map could not be challenged but that individual districts could make arguments in the lower courts.

“Americans do not like gerrymandering. They see its mischief, and absent a legal remedy, their sense of powerlessness and discouragement has increased, deepening the crisis of confidence in our democracy,” the brief from Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) read. “Partisan gerrymandering has become a tool for powerful interests to distort the democratic process.”

In December, the Supreme Court agreed to add a second partisan gerrymandering case, Benisek v. Lamone, to its docket. Unlike the gerrymandering case brought to the court last year in regards to Wisconsin’s state maps, the new case examined a single district in Maryland that Republicans argue was politically gerrymandered.

The court also ruled similarly in the Maryland case, saying a lower court was correct in not forcing the state redraw its map.

Meanwhile, in North Carolina, a federal court similarly ruled that its congressional districts were drawn to ensure “domination of the state’s congressional delegation” and ordered the state’s general assembly to redraw maps.

The Supreme Court ruled that the case would need to go back to a lower court.

In Abbott v. Perez, Justice Samuel Alito wrote in a 5-4 ruling that people challenging districts needed to “overcome the presumption of legislative good faith.” The ruling tossed out a lower courts ruling which invalidated the districts.

If you still need convincing about just how winding some of the boundaries are, Slate created a timed-puzzle game that shows you districts for each state and how oddly shaped they can be. Check it out here.

Are there alternatives to gerrymandering?

Yes! While most district boundaries are drawn by state legislatures, some states have taken different approaches.

For example, in Arizona, the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission is tasked with creating districts and is a non-partisan and independent group. This takes away the obvious political motivation parties have for drawing boundaries in ways that benefit them.

On its website, the Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission says its goal is to “redraw Arizona’s congressional and legislative districts to reflect the results of the most recent census,” and make sure that districts are “roughly equal” in population.