The election of President Donald Trump has seen a surge in activity from “antifa,” a radical collection of protestors whose confrontational tactics have spurred controversy, violence, and confusion across the United States.

The resurgence of extremist far-left groups committed to violently putting down a far-right, energized by Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric, has polarized the electorate. Some believe that violent neo-Nazi gangs and the trolling “alt-right”—a political faction defined by pro-white, nationalistic ideologies—have met their match. Others see the violence as a tragic and spiraling abandonment of civility in an era already defined by hyper-partisanship.

The conflict reached a dangerous new precedent in Charlottesville, Virginia, on Aug 12, when an alleged member of a white supremacist march drove his car through a crowd of counterprotesters killing a 32-year-old woman, Heather Heyer, and injuring some 20 others.

Since Charlottesville, antifa has fully entered the mainstream—primarily in the form of wall-to-wall negative coverage of the moment on right-wing news outlets. Even The Daily Show got in on the action, with host Trevor Noah calling the group “vegan ISIS.”

As Republicans and Democrats alike came out in an unequivocal condemnation of the act, Trump leveled partial blame at the “alt-left”—a made up and misleading term, but one most right-wing commentator understand to mean the anti-fascist left as well as groups like Black Lives Matter.

Here’s what you really need to know about antifa—and why you’ll likely be seeing more of the group in the coming months and years.

What is antifa?

Antifa is a loose and decentralized network of mainly leftist groups working to directly confront and resist the rise of fascism and racism.

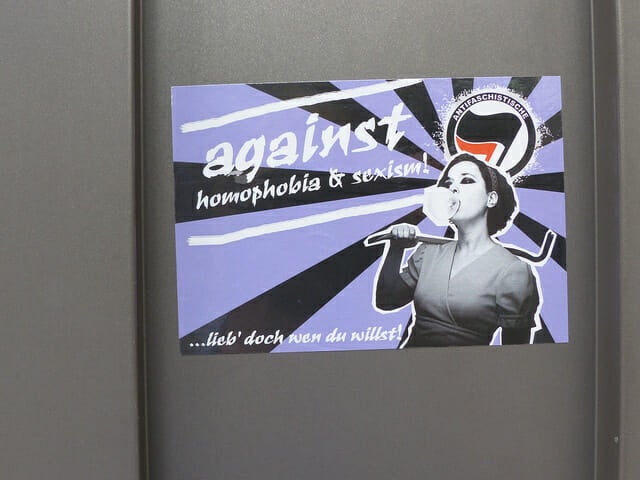

There is no leader or hierarchical structure in establishing new groups, so a self-started and local anti-fascist organization will self-identify with other antifa-affiliated groups through commitment in opposing sexism, racism, and classism. The network of protesters promotes the sharing of information between local chapters with the aim of defeating what they see as the primary evils of contemporary society.

The movement has gained notoriety for strongly advocating for the use of violent, direct confrontation and property destruction as a means of resistance. Some antifa activists justify it as a reflection of the violence enacted on minority groups by far-right gangs. But violence perpetuates violence and often buries the overall message.

Many American liberals refuse to support antifa and view violence as counter-productive, while those in the alt-right seize on the conflict, branding antifa as domestic terrorists and oppressive actors.

Right-leaning media outlets like Fox News will also often paint the activities of antifa and other organized demonstrations with the same brush, portraying peaceful protesters as violent thugs with no respect for the law—as seen in the NRA’s recent viral ad. The reality is not so black and white.

The visibility of antifa has been notable since Trump’s Inauguration Day, when demonstrations in Washington, D.C., turned violent, resulting in protesters and even journalists being caught up in mass arrests and charged with felony rioting. That same day, a viral video circulated across the internet showing a masked protester punching white nationalist and alt-right personality Richard Spencer in the face. The video became a cathartic meme for those on the left. The meme also became a hot talking point, raising widespread debate over the morality of violence against those who promote inherently violent ideologies.

Still, members of anti-fascist groups were showing up across the country to alt-right events and planned demonstrations in opposition. Organized and militant, antifa’s tactics of direct confrontation rose out of the shadows and into the national spotlight.

In early February, a student Republican organization at the University of California, Berkeley was set to host alt-right provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos. The event, however, was derailed when a large demonstration, attracting over 1,500 student protesters, erupted into violence after a small cell of anti-fascists showed up. Utilizing black bloc tactics (more on this later), this “group of about 150 masked agitators,” as the university described it, set fires, smashed windows, and threw fireworks at police officers, who struggled to contain the chaos.

The university slammed the “apparently organized violent attack and destruction of property” in a public statement published shortly afterward. This was an important early moment for the reinvigorated antifa movement of the Trump era. In the eyes of some, black bloc tactics had succeeded—organizers were forced to shut down the event “out of concern for public safety”—but antifa had caused an estimated $100,000 in damage to public and private property.

Since then, antifa has appeared in black bloc at rallies across the country. The most notable appearance since Berkely occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia, in mid-August, where antifa activists clashed with white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and white nationalists who congregated in the small college town to oppose the removal of a statue of Confederate leader Robert E. Lee from a town park.

Wait—what’s black bloc?

Often confused to be a reference to a specific political group, traditional black bloc is actually a protest tactic by which protesters tend to dress fully in black clothing and cover their faces. There are many occasions where black blockers will engage in a peaceful protest and merely cover up to avoid being identified and arrested. However, black bloc is also designed to allow demonstrators to engage in those who oppose them directly, as they see fit.

Each activist group utilizing black bloc tactics will act differently based on their own ethics. Under anonymity, some will continue to commit to non-violence, but others seize the opportunity to smash windows and cars or assault their opponents.

Is antifa a new phenomenon?

No. The movement, which has roots in Europe, traces back to the 1920s, with the emergence of far-right nationalist movements and fascism in countries across the continent.

In Germany, where the Weimar government was collapsing, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party was stepping into the power vacuum. With his own paramilitary gang violently roaming the streets, Hitler promised prosperity for Germany and a scapegoat in the form of the nation’s Jewish population—if only the people would give him the power to throw off the establishment criminals that had negotiated the country’s World War I surrender.

Leftists united in common cause to engage with what they believed to be a threat—fascism. Initially, the Red Front Fighters’ League was formed by communists, but soon, the movement grew to include a diverse group of those ideologically opposed to the right: anarchists, progressives, and socialists. By 1932, the German Communist Party had given it the name antifaschistische Aktion, from which the abbreviated antifa derives its name. Anti-fascists of the era regularly clashed in the streets with far-right gangs.

READ MORE:

- What is socialism, really?

- Here are all the ‘fake news’ sites to watch out for on Facebook

- The best political fact-checking sites on the internet

- The 13 best political podcasts to keep you informed

When the Nazis did seize power in Germany, however, the movement was quickly abolished along with political opposition of any kind—in word or in action. While anti-fascists who continued to resist faced death under the regime, their movement and directly confrontational tactics carried on, albeit underground.

In Spain, international brigades assembled to assist in the civil war fight against dictator Francisco Franco. In England, Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists were attacked in the streets by an antifa organization that was created by Jewish World War II veterans and members of the London’s Irish community, whose area Mosley wanted to march through. Although Mosley’s fascists had official permission to march, even the police could not offer passage because of the tens of thousands of demonstrators who showed up to throw bricks and build barricades.

Throughout Europe in the 20th century, wherever fascism raised its flag, the anti-fascists mobilized. Black bloc came about sometime during the 1980s in Germany. Many cite the 1,500-strong black bloc in 1986 that defended a squat in Hamburg as the first.

The American incarnation seen at Berkeley can be traced back to the early 1980s when it rose up in opposition to white power and emergent neo-fascist groups.

Back then, the Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP) of southern California and Minneapolis Baldies organized to thwart neo-Nazi skinhead gangs. Eventually, many of the anti-fascist organizations joined together under the name Anti-Racist Action (ARA) in 1988. The ARA worked in opposition to white supremacist gangs and the Ku Klux Klan.

Although the ARA maintained a low profile through the late 1990s and 2000s, it was reimagined as the Torch Antifa Network ahead of the 2016 presidential election. Trump’s presidency and style of extreme populist politics, a blend of nationalism and inflammatory rhetoric, energized far-right organizations, which in turn has galvanized antifa.

Antifa and the internet-native alt-right

Antifa is now seeing a surge of support and condemnation across the country, with affiliated chapters appearing in almost every major U.S. city. Instrumental to the movement’s growth has been its commitment to social media. Anti-fascists have been finding one another on Facebook or Twitter by city and collectively banding together on websites like Reddit.

“As an empirical measure, our Twitter followers have almost quadrupled from the beginning of this year,” organizers for NYC Antifa told the Nation in January. “[N]ew groups are popping up everywhere, and we are fielding requests from all over the country about how to get involved.”

Various antifa chapters operate dedicated news websites like Anti-fascist News and It’s Going Down, which report on antifa activities and closely monitor key individuals on the far-right, not unlike the alternative media outlets that serve alt-right communities.

In recent years, however, the internet has become the playground of the alt-right and, as a result, has become a new front line for the two groups. Traditional antifa black bloc tactics are of little use in the digital sphere, and the far-left has had to adopt new strategies in this age of digital battle.

While independent leftist blogs have sought to dox—to expose targets’ identities and whereabouts—of white supremacists in the past, alt-right sympathizers on 4chan and Reddit have made it their mission to scan videos and image from rallies where antifa activists are present to dox their enemies back. In the age of crowdsourced investigation, the stakes have escalated.

In May, BuzzFeed News revealed that Trump supporters had been quietly assembling a document containing the names, addresses, social media profiles, and phone numbers of thousands of suspected antifa members. Trolls, likewise, have created fake Twitter accounts to mock and discredit the antifa movement—beyond the negative press that comes with burning cars and smashing Starbucks.

Internet games of cat and mouse can get messy, and in return, antifa activists have doxxed members of the far- and alt-right as well as journalists they perceive as providing them with a platform.

It’s in towns and cities that antifa, by its historic mission, hopes to make its presence most felt—whether by stomping those they perceive as fascists or radically aligning with vulnerable people they believe need their help. The movement is still committed to street activism. NYC Antifa even tells followers that to win the “propaganda war” they’ll need to utilize graffiti and posters—in contrast to the meme wars that the alt-right wages across the internet.

Like their alt-right counterparts, antifa is not a singular entity but a diverse network of factions ostensibly committed to similar ends. As such, it also expresses itself with the diversity of the radical grassroots organizations that are directly or indirectly represented within it. These groups are often aligned with broader far-left political causes and ideologies.

After Trump’s election victory was announced in November, the blog NYC Antifa released a statement calling for solidarity and organization against “increased deportations, the registration of Muslims, bans on abortion and birth control, attacks on LGBTQ people, anti-Semitic populism, and the newfound electoral coalition of U.S. White Nationalism.”

Currently, groups associated with antifa employ several strategies of resistance beyond the fighting that makes headlines. In New York, the Rapid Response Network and New Sanctuary Movement work to protect undocumented immigrants from Immigration and Customs Enforcement. To support those in communities that suffer harassment and prejudiced attacks, neighborhood antifa activists offer training.

Other antifa elements just want to punch Nazis and wreak havoc.

Whether you see them as allies or enemies, antifa is a symptom of and catalyst for the extreme political divide within Trump’s America. This culture war is only beginning—online and in the nation’s cities. If the rise of antifa is anything to go by, the division is actually widening and, for some, so is the disagreement over what democracy should look like.

Antifa news

Aug. 26, 2017: An antifa activist was shot in the crotch with a tear-gas canister during a protest against President Donald Trump. The man, later identified as 29-year-old Joshua Cobin of Arizona, outed himself in an ‘Ask Me Anything’ thread on Reddit, resulting in his arrest.

Aug. 28, 2017: A protest in Berkeley, California, turned violent during a clash between antifa activists and right-wing protesters. Police arrested more than a dozen people.

Sept. 4, 2017: An investigation by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Journalism found that organizers of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, specifically told fellow attendees to wear polo shirts and khakis—rather than, say, white hoods—as a way to hide their racist beliefs.

Sept. 28, 2017: Pranksters on Tumblr mocked antifa by jokingly claiming that “ANTIFA” stands for “Activism, Networking, Training, International Outreach, Finance and Accounts payable.” Laughter ensued.

Oct. 2, 2017: Following the deadly mass shooting Las Vegas, which left 59 people dead and more than 500 injured, far-right voices online claimed the shooter was an antifa activist. At the time, police had released little information on the suspected shooter, Stephen Paddock, whom they later said was a 64-year-old avid gambler. Authorities made no connection between antifa and Paddock.

Oct. 30, 2017: Twitter suspended a popular user, Krang T. Nelson, after they made a joke about antifa activists beheading “all white parents and small business owners in the town square” on the day of an anti-Trump protest. Many complained about Twitter’s haphazard rule enforcement, which left Nelson suspended while unnumbered pro-Nazi accounts remained online.

Oct. 31, 2017: Far-right personality Mike Cernovich, an outspoken opponent of antifa, attempted to claim that antifa activists held a sign defending pedophilia at a protest in New York City. Reports later revealed that the sign was planted by trolls who hoped to paint antifa in a negative light.

Nov. 6, 2017: Repeating the tactic used after the Las Vegas shooting, far-right voices online attempted to link a gunman who killed 26 people at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, on Nov. 5 to antifa. Police had made no such link and had not released a motive at the time of the far-right rumors.

April 4, 2018: Al Jazeera filmed a documentary on the rise of antifa in the U.S. since the inauguration of Trump, spending time with an antifa cell in Portland, Oregon.

The filmmakers describe the different roles that individuals within the movement take on, both online and offline. However, the decentralized and leaderless nature of antifa means that not every cell will organize in this way.

Antifa researchers, identified as hackers within the film, work to expose the identities of individuals on the far-right and publicize where they live or work. They do this by scanning images taken at demonstrations of those in attendance and have successfully exposed where white supremacists have appeared alongside far-right demonstrators,

Street medics and street fighters are involved in more physically confrontational tactics, showing up wherever the far-right does. The film begins featuring one activist, calling himself Hex, who was shot during a heated exchange outside a Milo Yiannopoulos speaking event.

Antifa’s more violent tactics are depicted as at odds with the traditionally non-violent student and left-wing movements associated historically with the civil rights struggle and Black Lives Matter. However, this apparent tension seems to dissipate on the frontlines. In Charlottesville, antifa are shown defending non-violent faith-based groups from attacks by neo-Nazis—something which one minister in attendance expresses gratitude for.

Parallel to antifa, the film features Trump supporter Joey Gibson and his alt-right Patriot Prayer group, who are clear that they attend protests hoping to bait antifa and provoke them to violence. Gibson is shown attempting that in Berkeley, California, where he is pushed and forced to leave a demonstration by antifa.

While Gibson depicts the incident as difficult for him to revisit, an anonymous antifa medic shown the same footage says the fairly typical tactic of protecting a “zone” as a success in making the right-wing provocateurs leave.

“Big fucking deal,” the masked activist laughs. “They’re fascists. They should leave.”

The film ends with Hex’s recovery from the shooting. Hex describes his belief in restorative justice in choosing not to testify against the woman that shot him and refusal to participate in a process that will imprison another person—seeing the state itself as inherently fascist in nature. Although part of antifa and sympathetic to its tactics, he expresses his desire to de-escalate violence within society entirely.

Watch the full film below:

April 10, 2018: Homeland Security-run centers across the country have been intensely monitoring antifa, according to documents acquired via FOIA by MuckRock, and consider the left-wing radicals and not white supremacists as “the greatest threat to public safety.”

One DHS report, released on Aug. 11, one day before the clash at Charlottesville, describes antifa as the “principal driver” of violence at rallies where white supremacist groups had also been present. In internal educational keynote slides, Northern California Regional Intelligence Center blames antifa for initiating the altercations in almost every instance.

MuckRock describes how other documents in the 1,800 page FOIA haul appear to downplay the lethal threat from white supremacist groups, although does include intel on violent groups on the far-right. Antifa, however, appears throughout as a central concern in law enforcement briefings and operational information across the country.

Editor’s note: This article is regularly updated for relevance.