Suzanne Dikker, a cognitive neuroscientist at NYU and Utrecht University, cautioned the crowd gathered at Williamsburg’s Cantina Royal last night that her “NeuroTango” experiment could prove disappointing.

She had previously used EEG devices to scan the brainwaves of the artist Marina Abramović and another subject as they maintained silent eye contact à la her popular performance piece “The Artist Is Present,” picking up only fleeting moments of synchronicity, those moments when the two minds’ electrical impulses are in phase and equally intense.

But as host and moderator Graciela Flores explained in her introduction, tango provides a unique experimental platform. The seductive, surprisingly free-form Argentine dance is “all about connectedness, mental and physical,” she explained, a wordless, bodily communication—most people even shut their eyes. “It’s a question of how two people can move as one.” She drew a tantalizing analogy that spoke to the cognitive mysteries at work: “Tango dancers talk about the high.” Indeed, before the evening was over, one dancer, John Osburn, spoke of being “lost in a tango daze.” (Osburn danced with Laura Real; Nan Min and Jack Hanley formed a second pair.)

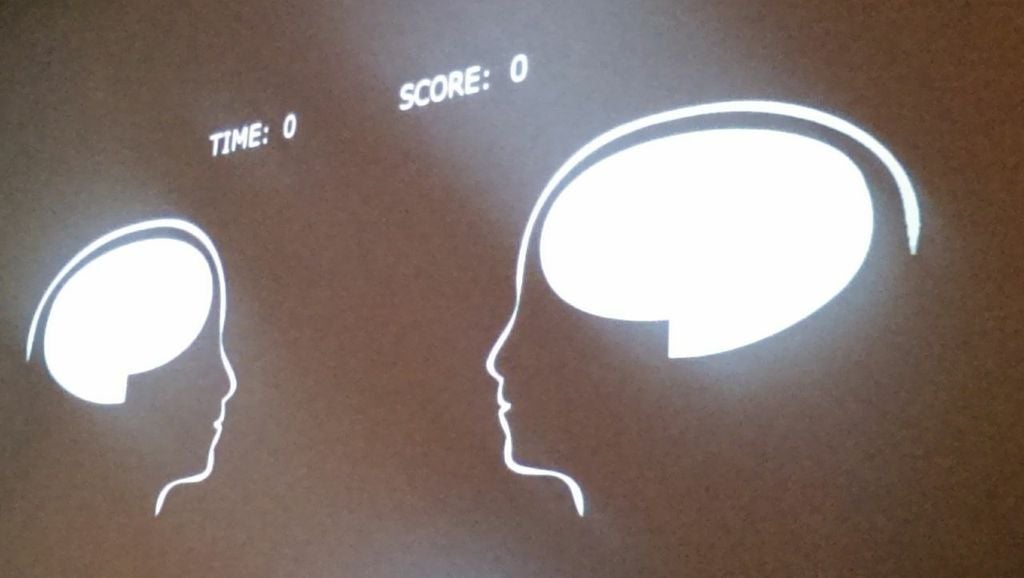

There were some technical difficulties to contend with, but eventually the four veteran dancers took to the floor with black, spidery sensor-helmets strapped to their heads. Because the actual EEG readouts, transmitting what Dikker likened to biological radio signals, are so confused and jumbled on screen, she opted for a more dynamic display that succinctly characterized the flood of data pouring in: each partner was represented by the cross-section of a head, and the better the dancers’ brains mimicked each other’s patterns, the more the two heads would overlap. The more their neural activity lined up, the higher the total “score.”

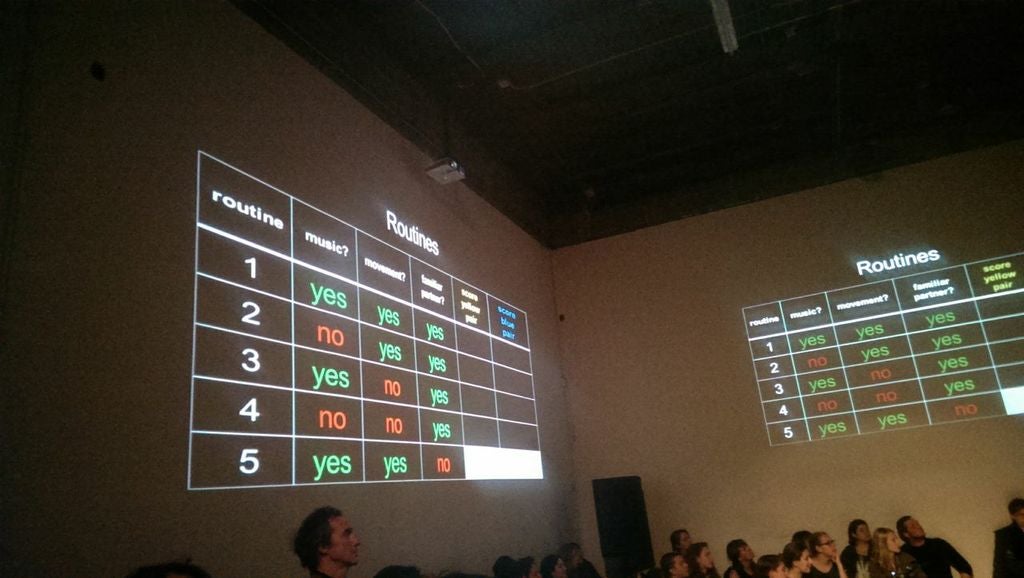

After a few minutes of normal tango, a few variables were introduced. The next dance was done entirely without music, the performers simply moving and sliding about the floor to some imagined tune. Next, they stood still while tango music played, effectively “dancing in their heads.” Finally, they swapped partners to see how a sense of unfamiliarity affected the outcome. (Dikker had previously noted the human brain’s talent for rhythmic, predictive, and adaptive responses.)

In the first instance, the “blue” pair synchronized “suspiciously well,” Dikker said—she even feared the equipment was malfunctioning at one point. The yellow pair’s icons more resembled, as one middle-aged Brooklyn man skeptical of this “junk science” had it, “me and my first wife going at it.”

Throughout the subsequent variations, Jack Hanley, one of the blue dancers, proved to be almost constantly simpatico with whomever he danced with. One woman in the audience—a healthy mix of scientists and artists attended—noted that in Argentine tango, the woman is meant to be submissive and let the man lead, wondering if Hanley or the two female dancers were especially adept at transmitting certain vibes.

Hanley said he kept his steps simple, then addressed the gender/sexuality dynamic: “I’m also gay. Dancing with a beautiful woman is wonderful, though I would bet my brain is doing something different when I go out dancing with a hot guy.”

Tellingly, Dikker noted, the dancers synchronized least when they were forced to stand still and imagine their movements—even when they had to dance sans music, they did better than when simply hearing the same song and maintaining physical contact. Pressed on what we could deduce from what we’d seen projected on the walls, Dikker was hesitant: “Not much,” she admitted. “We often see similar brainwaves in response to shared environmental stimuli.” At best, we could surmise that the tango requires a heightened sensitivity to external cues. As the experiment and lecture gave way to a full-blown tango party, it seemed that some people were more satisfied with the mystery. “We’re doing to dance until they kick us out,” Flores declared.