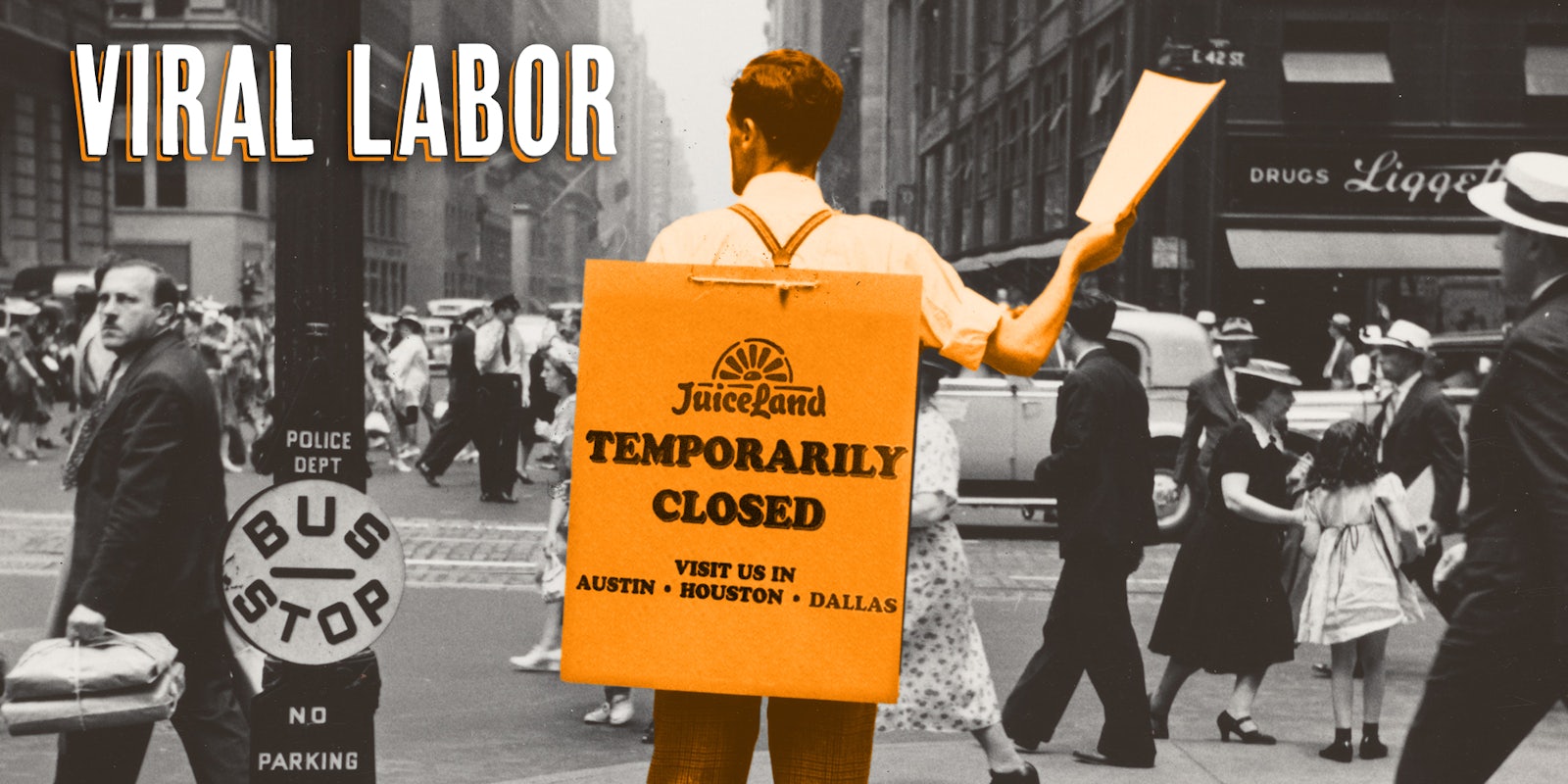

Labor organizing no longer solely looks like street-sweeping protests or public rallies. At least, those methods can’t work alone. Today, labor movements are shared on Instagram, Craigslist, and other online platforms.

Amid negotiations for an ongoing strike of its production warehouse and storefront workers, Texas-based smoothie company JuiceLand halted all cooperation with the strikers. When the production workers shared a statement to the strikers’ Instagram account, @juicelandworkersrights, calling on their higher-ups to admit the company’s faults, the executives drew the line.

“What we see is the opportunity for JuiceLand to put their ethics over money by becoming a leader in this movement for fair and sustainable workers’ rights for all,” the statement reads. “This starts with taking ownership for their part in the upholding of these systems.”

JuiceLand, a company founded in 2001 that boasts fresh smoothies, healthy eats, and a “fun” work environment, now has 35 storefronts across Austin, Houston, and Dallas. Its Austin-based production workers began striking May 14, after expressing their concerns about hostile working conditions and being forced to work beyond their scheduled work hours. Workers said they had an unproductive meeting mediated by the human resources department, so they walked out.

The production workers called up the storefronts to let them know they were striking, with some of the shop workers striking in solidarity, which closed down nine shops by the end of the weekend. From there, shop workers shared their own demands, complaining about the $8 per hour base pay and the racism and sexism some said they faced in the work environment. The strikers formed their Instagram account, which allowed them to communicate directly with the public, and chronicled their negotiations with the executive team at JuiceLand as they happened.

While the strikers’ bold strategy of online organizing brought the movement right to the public, it didn’t come without its risks. The post on May 20 from production workers led the executives to cancel the meeting they had scheduled the next morning.

“After we sent that out, I think by 8 o’clock that night, they had emailed us and said that they canceled the meeting because, ‘It’s clear that we have an agenda,’” one striker told the Daily Dot. “Which, it is clear. We’ve always had an agenda: Fix the actual issues instead of glossing over them.”

That’s where the negotiations stopped and the hostility began, the strikers said. Some of the strikers received cease-and-desists citing defamation from upper management for posts made on the account. JuiceLand executives haven’t met with the strikers since canceling the meeting. Soon after, they sent emails to its striking employees on June 3 notifying them that their positions had been either already permanently filled or soon would be. The company hired strikebreakers, also known as scabs, to replace them, and soon a full-fledged attempt to bury the strike began, the strikers said.

JuiceLand declined the Daily Dot’s request for comment.

The JuiceLand strikers used the momentum they gained on social media to build collective power. Though negotiations have halted for the moment, the workers are looking at other ways of holding the company accountable—and their Instagram account remains an accessible tool for them to reach other workers, their community, and JuiceLand’s clientele.

The JuiceLand strike is representative of modern-day labor organizing. Instead of organizing street-sweeping protests, labor movements are shared on Instagram (or at most, exist in tandem with physical protests). Social media and technology have provided workers with new avenues of gaining power, exhibited by both the JuiceLand strikers and Rideshare Drivers United, a national organization of Uber and Lyft drivers founded in Los Angeles in 2017.

As Erin Hatton, an associate professor at the University of Buffalo’s Department of Sociology, told the Daily Dot, traditional “capital L” labor unions have been slow to adapt to the internet and social media. But newfound labor organizers have taken digital organizing by the reins.

Accessibility of digital spaces

Traditional means of labor organizing are difficult. While taking up physical space is powerful, Hatton noted that it can be dangerous for workers and hard to access—which is what makes digital spaces so appealing.

“The barriers to physical organizing are one of the many reasons why unions have been declining,” Hatton said. “It’s extremely difficult to organize workers for so many reasons, not least of which is just the economic realities of their lives, the fear of being fired because if they’re not working there, they need to be working somewhere else to feed their family.”

Mo, a Rideshare Drivers United volunteer who is helping to jumpstart the organization in Austin, said low pay and long hours add to the challenge.

“For a large majority of us, we don’t have the time to spend for causes other than supporting ourselves and helping our family, because we have to be on the road,” he said. “You have to be out in the field, rain or shine, snow or whatever. You have to keep driving.”

Mo has been a ride-hail driver for seven years, and he says the conditions have only gotten worse. Uber slashed mileage pay rates from $0.80 to $0.60 in 2019, while prices have appeared to simultaneously increase for riders. Both Uber and Lyft have failed to provide proper support for damages and operational expenses to their employees, who are legally classified as independent contractors. Drivers are also not provided health benefits.

Mo found Rideshare Drivers United through Craigslist and is helping to spearhead the movement in Austin, where it is just beginning.

“I thought it was a scam,” he said with a chuckle, “but I just put my name down and I thought, ‘Well, however bad it is, let’s just see where this goes.’”

Like Mo, ride-hail drivers across the nation are learning about the organization and their demands through the internet. In a 2019 study, Brian Dolber, an assistant professor at California State University San Marcos and volunteer with Drivers United, found that pairing social media with traditional means of organizing was instrumental in modern-day labor organizing, particularly for workers who lack the water-cooler chat that could lead to union organizing.

Recruiting atomized workers

For gig workers like ride-hail drivers, who are classified as independent contractors, worker solidarity can be hard to foster, as they lack a traditional shared workspace like an office or a factory. Hatton said because these workers are atomized, organizing is all the more complicated, which is where the benefits of digital recruitment come in.

App developer Ivan Pardo joined Rideshare Drivers United as a volunteer in 2017, building them a platform to send encrypted texts to drivers, through which the organization collected survey data on the issues most important to drivers.

This helped form the Drivers’ Bill of Rights, which demands fair pay, transparency from apps on fare breakdown for both drivers and customers, recognition of the organization from both Uber and Lyft, and a cap on the number of active ride-hail vehicles to slow carbon emissions and prevent excessive traffic.

In addition to text technology, the team also created an app for drivers to communicate with each other, especially ahead of national rallies or strikes. But the prime factor in growing the organization has been targeted Facebook posts, which they promote through the social media website to reach drivers. The study found social media advertising to be a low-cost way for early-stage labor organizations to grow their numbers, with the group being able to gain new members at only $0.73 per person by 2019.

Sharing worker experiences

While the JuiceLand striker’s Instagram account became a space for direct communication with the public on where negotiations stood, it also operated as an anonymous line for workers to share their work experiences—with fewer threats to their livelihood.

Hatton emphasized that digital spaces offer workers new avenues to find patterns in their experiences and, in turn, solidarity. An anonymous platform provides a relatively safe space for workers to make those connections.

“Being recognized for one’s hardship is incredibly important on an individual level,” Hatton said. “But that sharing of stories, hearing of workplace experiences of the common workplace is the foundation of worker organizing. […] The internet provides this great platform to do so anonymously because workers are under a lot of pressure, coercive pressure specifically, to not speak up, not pushback, to not give voice to those problems that they’re experiencing, especially when the working conditions are dangerous or are full of harassment or racism and discrimination.”

The JuiceLand strikers recognized this pattern after sharing a couple of worker experiences. They still have a large number of unpublished direct messages from workers who felt compelled to speak out after seeing others do the same.

“When we put those stories out there more came in, because people were finally comfortable speaking up and saying what their problems were and what their experiences have been,” one of the organizers said. “[…] I’m glad it’s been able to help people in that way.”

Who controls the narrative

JuiceLand’s executives have also taken their own measures to try to control the narrative, the strikers said, including prohibiting comments on certain posts from JuiceLand’s main account and deleting negative comments on others.

“No one can publicly leave a comment about how shitty they’ve been to the JuiceLand strikers, and how essentially they fired them by permanently replacing them,” they said, “and they’re just trying to control the conversation there, silencing us and our supporters, or doing the best that they can.”

However, the strikers noted that they actively utilized social media in order to contact the same type of audience as JuiceLand’s young, hip clientele. Hatton agreed that social media can, in some way, level the playing field of communication.

“The internet has been co-opted by corporate interests so much that they’re kind of reclaiming apps and social media technology for worker power, which is exciting,” Hatton said. “I think we haven’t seen the end of it, and we also haven’t seen it at its full potential.”

Though they remain on strike, the workers have slowed their postings on social media as they continue to work on holding JuiceLand accountable. Despite challenges that have risen from communicating their stories and updates publicly, the strikers urge other workers to do the same, as it was an important part of building solidarity across the board.

“It may seem impossible to get these issues out there, get your story out, or any stories or experiences out and with this, clearly, we were able to do it,” one of the JuiceLand strikers said. “We were able to make this bigger than we thought we would make it honestly.”