The problem with a lot of personally and socially beneficial things is that they’re kind of a hassle. Take exercise, for example. Exercising is a great way to stay healthy, but blocking off an hour each day to get all tired and sweaty isn’t always feasible. That’s why building exercise into your daily routine is such a great idea. Biking to work instead of driving kills two birds with one stone.

That same concept can be applied to a task that’s literally the opposite of exercising: crowdsourced data entry.

Crowdsourcing platforms like Wikipedia and Github are among the most important sites on the Internet, but they require a level of sustained time commitment that only a select few are willing to make.

A team of computer scientists at U.C. Santa Cruz and Stanford recently banded together to figure out how to get more people involved in crowdsourcing. Their solution? Build it into something we already do dozens of times a day—unlocking our smartphone phones.

In a paper presented at the prestigious ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems held earlier this year in Toronto, the researchers outlined an idea called twitch crowdsourcing, which gives users who have the requisite smartphone app with a simple task that can be completed in a second or two every time the phone is unlocked.

The concept is relatively similar to reCAPTCHA, a system requiring users to look at pictures of distorted text and enter the words contained therein. Not only does reCAPTCHA prevent automated bots from accessing restricted areas of websites, but also helps digitize scanned books.

The Twitch app, which is available for free download in the Google Play app store, currently boasts three different tasks, each of which could be easily put to use toward a larger, beneficial goal. ?We were concerned about ensuring that the tasks were fast and simple,” explained the study’s lead author, Arjan Vaish. ?But we also wanted to make sure that each of the tasks served a larger purpose. Something that made a bigger impact.”

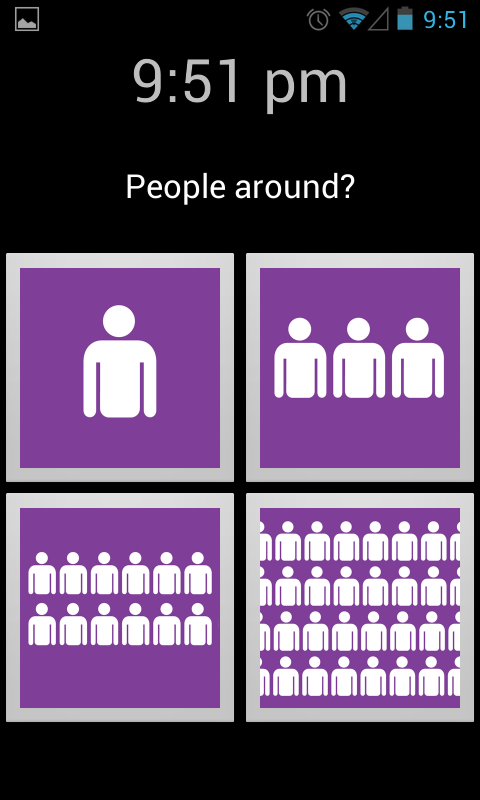

The first task is an instant census where users report basic facts about themselves and the world around them—what are they are currently doing, how many other people are nearby, their current energy level, etc. Since each rating is geotagged with the user’s location, the study’s authors envision it could be used to ?help create a human-centered equivalent of Google Street View, where a use could browse a typical crowd activity in an area.”

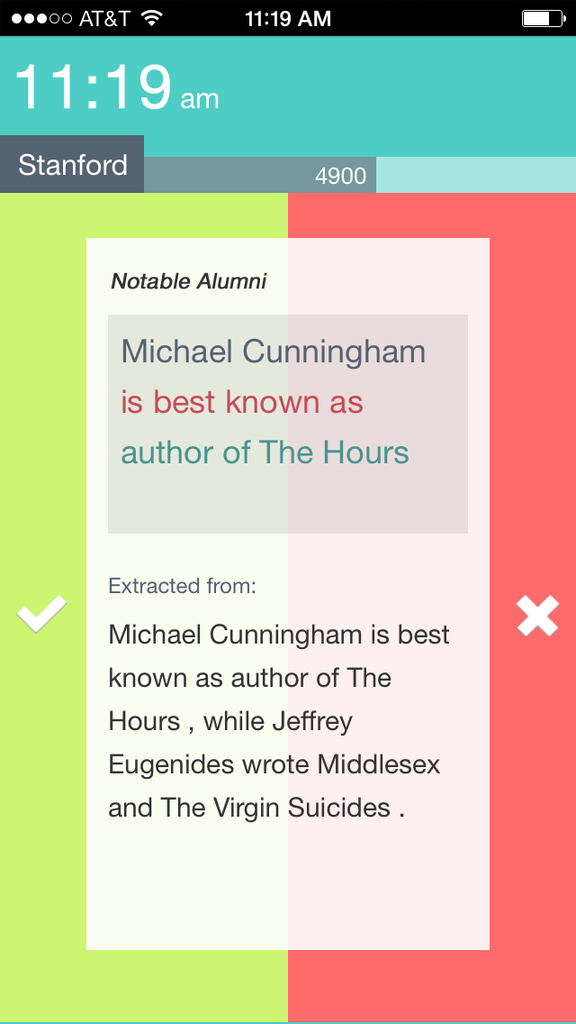

The second involves picking between two stock photos to determine which one is a better representation of the idea being expressed. The third is rating the quality of short, algorithmically generated summaries of longer pieces of Web content. This is supposed to help make human-created data understandable by machines.

This task is particularly important because it allows search engines to return more robust results, and large volumes of human feedback is crucial. The paper lays out an example:

Search engines no longer only return documents—they now aim to return direct answers. However, despite massive undertakings such as the Google Knowledge Graph, Bing Satori, and Freebase, much of the knowledge on the Web remains unstructured and unavailable for interactive applications. For example, searching for ‘Weird Al Yankovic born ’ in a search engine such as Google returns a direct result ‘1959’ drawn from the knowledge base; however, searching for the equally relevant ‘Weird Al Yankovic first song,’ ‘Weird Al Yankovic band members,’ or ‘Weird Al Yankovic bestselling album’ returns a long string of documents but no direct answer, even though the answers are readily available on the performer’s Wikipedia page.

While the initial build of the app only has a few options for tasks for users to complete every time they unlock their phones, the possibilities of what could be done with the data are virtually limitless.

Viash posited a few other examples, such as using the platform for a tutoring app teaching things like grammar and spelling, where users would have to answer a simple grammar question every time they opened their phones. He also suggested that Twitch could be leveraged to help the visually impaired interpret the world around them by letting them take pictures of objects or images on their smartphones and then have people around the world use Twitch to identify those objects.

While Viash noted that his team has made a concerted effort to make the tasks in the test phase noncommercial, he has been approached by private companies (including a noted multinational publishing house) interested in monetizing this creation.

It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where companies would direct micro-payments to Twitch users for answering survey questions or organizing large datasets on a piecemeal basis.

None of this would work if Twitch users found the process significantly more annoying than standard unlock screens. To test if this was the case, the study’s authors publicly deployed the app and tracked how the 82 users who downloaded the program used it over the course of one month.

They found that about half of the people who downloaded the app kept it on their systems for longer than a single day and the average duration of use was the full month. Twitch, and all of its potential, isn’t any more onerous than how we currently unlock our phones. But with Twitch, we could give the tedious movement a purpose. Beyond, you know, getting us to Candy Crush.

Photo via Twitch Crowdsourcing