President Donald Trump’s temporary travel ban is set to return this week, and with it, a lot of questions—and a host of problems you may have never considered.

Nothing serves the goals of social engineers as well as times of uncertainty. Social engineers are cybercriminals who invest in human error rather than technical flaws in systems, “The current situation in the U.S is a fruitful soil for black hats and gray hats and their social engineering activities,” says Boris Kuharić, cofounder of project nullbeat, a virtual security software.

Social engineering involves capitalizing on strong emotions such as fear and anxiety to force targets to commit mistakes such as giving away sensitive information or execute malicious applications on their devices.

And at present, there are a lot of people across the U.S. and beyond its borders who have reason to feel vulnerable and make hasty decisions, thus becoming attractive targets for cybercriminals and online fraudsters. “The situation caused by recent events eases the process of getting personal or confidential information and data,” Kuharić says.

“There is a lot of anxiety in the U.S. now over immigration policies and social engineers often target groups of people stressed over a particular situation as they are often desperately seeking a solution,” says Bill Bullock, CEO of encrypted email service SecureMyEmail.

Who are the potential attackers?

“In the current climate of immigration concern, it’s possible for a fraudulent company to prey on the needs of those originating from the countries currently targeted by the immigration ban,” says Edward Robles, CEO of Qondado, a Puerto Rico based cybersecurity company focused on solving authentication and transaction security problems.

According to Robles, the fear and anxiety surrounding the travel ban creates a fertile ground for fake visa expediting or approval services. “The nature of the immigration process itself is one that requires sharing of official documents and identification,” Robles says. “A malicious actor could not only defraud a concerned person or their loved ones of funds but also gain access to critical information that would allow them to steal an identity and/or create accounts in their names.”

Aside from financial criminals, this particular situation is also favorable for oppressive regimes. A three-year research by Amnesty International technologist Claudio Guarnieri and the independent security researcher Collin Anderson presented at Black Hat Security Conference last year shed light on how the Iranian government used social engineering tactics to target exiles, dissidents, and activists.

What does an attack look like?

Social engineers’ favored method of attack is phishing emails—legitimate-looking letters, ostensibly coming from credible and authoritative sources that lure recipients into downloading malicious content, visiting infected sites or revealing sensitive information. “Attackers trick their victims by manipulating the sender’s identity,” says Kuharić. “The sender’s identity is one of two critical factors to establish trust with the receiver in social engineering attacks. The second factor is the content of the email or text message, which has to be appealing to receiver.”

“It’s basic psychology,” Bullock adds. “If the hackers add a target’s personal information, usually gathered from social networks and online forums, they can engage in something called ‘spear phishing,’ which specifically targets a victim and exponentially increases the target’s level of confidence that the email is legitimate.”

“Spearphishing emails could leave one particularly vulnerable in that a message claiming to be from an attorney or immigration official or service could push someone to a site where personal information or payment is requested in return for immigration assistance,” Robles says. “An individual could be very sensitive to the topic and therefore let their guard down and ‘wish’ or ‘hope’ for the kind of help supposedly being offered only to find themselves defrauded of their identity or funds.”

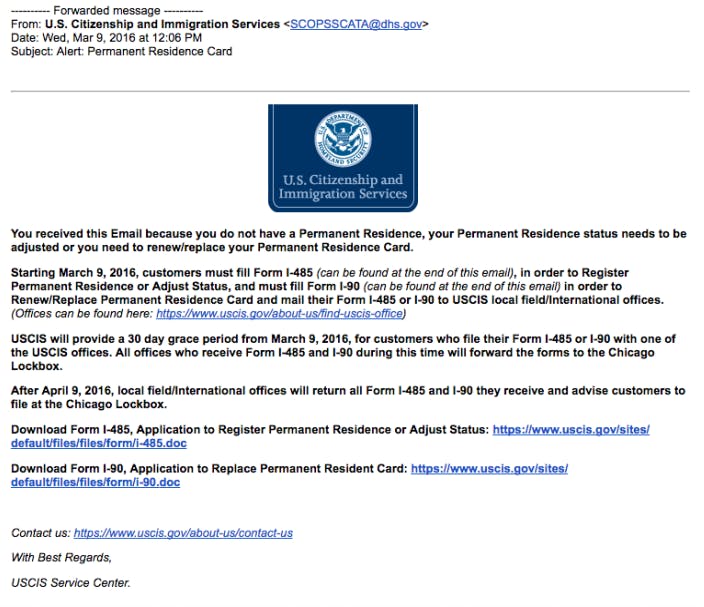

In their research, Anderson and Guarnieri came upon several emails where the attackers had impersonated the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, informing the recipient, “You received this email because you do not have a Permanent Residence, your Permanent Residence Status needs to be adjusted or you need to renew/replace your Permanent Residence Card,” and containing links to relevant forms.

Now more than ever, such emails might look convincing to potential targets of social engineering attacks. “A sense of urgency is created which could cause someone to share personal information out of fear,” Robles says.

Attackers might also leverage social media are also a potential attack vector to make their attacks look more authentic.

“Use of social networks will likely increase, not only to gather information to make fake emails seem more legitimate but also as a platform for attack in and of itself,” says Bullock. “The emails could contain highly specific information gathered from social networks and look very official and legitimate with bogus case numbers, spoofed websites, and the like. The victim then clicks on a link, downloads a file, and/or provides further personal information and they’re in a world of hurt.”

How to protect yourself

There are specific ways that you can detect and prevent phishing and spearphishing attacks.

“Never share personal or financial information on social media, email or in response to a phone call,” Robles says. He also stresses that government entities or related processes rarely engage an individual via email or by phone and usually use postal mail. “Know for certain who you are speaking to or communicating with and validate their intent and their organization by looking up official phone numbers and/or communication protocol. Ask for a number to return the call and confirm the information with the information you find online.”

“Is the email too good to be true and asking for personal information?” Bullock says. “Does it contain misspelled words or use poor grammar?” These are some of the questions you should ask yourself before placing trust in the sender of an email.

Bullock also mentions additional measures such as making sure the “reply to” matches the “from” field and hovering over any links to make sure they match the organization. “Of course, this won’t protect you from the really targeted ones,” he reminds. “So, overall, you should click on nothing and go old school and call the actual group or person or go through their official website in the case of an organization.”

Beyond emails, you should engage in basic cyber-hygiene, often-overlooked measures that can fend off most attacks, such as keeping your operating system and antivirus software up-to-date, using strong passwords and multifactor authentication on your online accounts, and encrypting your data. A defense strategy founded on sound judgment and best security practices can make it harder for hackers to reach their goal.

Ben Dickson is a software engineer and the founder of TechTalks. Follow his tweets at @bendee983 and his updates on Facebook.