The year is 2014. Freedom in Turkey is in active decay.

Seeking to further consolidate his power after over a decade in office, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declares he will “eradicate” social media services like Twitter after users link him to corruption.

“I don’t care what the international community says,” Erdoğan says at a campaign rally. “Everyone will witness the power of the Turkish Republic.”

That display of raw state power was met with anti-censorship graffiti that’s since become iconic. Armed with spray paint and technical know-how, dissidents painted buildings with instructions on how to circumvent Turkey’s Twitter ban alongside the words, “let your bird sing.”

For a certain kind of world class cybersecurity professional—a job that can virtually guarantee a high salary no matter what kind of work you do—there are at least two ways to react to this kind of clash spilling over from cyberspace into the streets and back again: join the establishment or help fight back.

An entire industry of mercenaries do the work of oppressive governments for pay—whether it be hacking, censorship, deep surveillance, or all of the above wrapped into a single lucrative contract. Just last week, a company called NSO was caught doing the highly profitable work of spying on human rights activists on behalf of the United Arab Emirates with brutally sophisticated and expensive never-before-seen hacks against Apple’s iPhone.

For that breed, events like the Turkish clashes are a market opportunity to sell to governments making aggressive moves online.

For another type, Erdoğan’s display of “power” was a moral opportunity to build new tools allowing more people to beat censorship around the world.

When he saw the graffiti in Istanbul, Joshua Lund made a choice.

“It’s hard to say how many users it has. But I get the impression that it’s helping people. I find that really satisfying.”

Lund first found a free and open cyberspace as a child at his local library.

He’d park himself at the Gopher terminal—old tech heralded on occasion as a manifestation of the purity of the early internet—that let him have conversations with other people around the world, dialing up to online bulletin board systems (BBS) and diving into an increasingly connected world.

“The promise of the internet as something that can connect people across vast differences and expose people to new ideas is really important to me because that was so exciting to me growing up,” Lund says.

“Even before the World Wide Web, and especially after the World Wide Web, connecting to a BBS and downloading an mp3 that you couldn’t even buy in the United States was a pretty mind blowing idea to me.”

News of Turkey’s government blocking social media—specifically painting crosshairs on Twitter users’ free speech—hit hard in headlines in a world at a time when the public had begun to take a deeper and more concerned interest in internet censorship and surveillance. The world watched in real time as a country deeply intertwined with the West plainly tried to kill millions of connections they found displeasing. It sparked a shockwave of discontent.

“There was something that really hit me in a visceral way about that,” Lund explained, “because that’s not the way that internet should work. Because that’s not the way the internet worked for me growing up. It was a way to really freely exchange ideas and learn more about the world.”

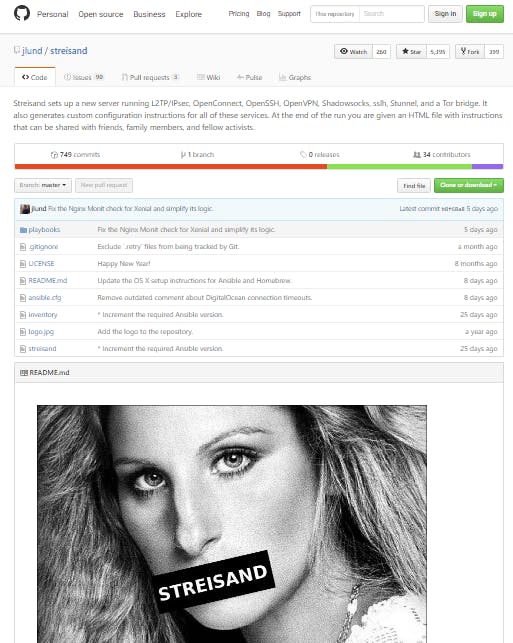

Starting with photos spreading of the anti-censorship “bird song” graffiti, the Turkish trouble led directly to Lund spending his off-hours working on and then launching a free software project called Streisand.

Streisand is named for the American pop star, Barbra Streisand, whose name is now synonymous with the unintended consequences of censorship: The information you try to destroy often becomes known far more widely after a censorship attempt than it would if you did nothing.

Streisand sprints to help users set up a virtual private network (VPN) with more than half-a-dozen powerful and transparent privacy tools that can help beat the diverse and always changing ecosystem of censorship that exists from Beijing and Astana to Istanbul, or—more pedestrian but also more common—from schools to airport Wi-Fi.

“It sets up a wide variety of VPN software, which gives you flexibility when you encounter different things and hopefully find something that works,” Lund explained. “The point is to take a bunch of stuff that was really difficult to set up manually by hand and package it all together in a way that provides you with a lot of flexibility with the diverse range of networks you encounter in the real world.”

The unintended consequences of Turkey’s major and sustained move toward internet censorship—Turkey’s government under Erdoğan, now president, has shut off social media in the country at least six times already this year—is the creation of a sophisticated anti-censorship project that’s now being used around the world.

Without the former NSA contractor Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations and Turkey’s social media crackdown acting as the dual catalysts, Streisand wouldn’t exist at all.

Streisand targets two groups of users: The technically proficient who can set up their own server in a few minutes with a couple of bucks, and the rest of us who simply want to use a trusted VPN server to protect their internet traffic.

“The other use case I was interested in hitting was someone who is technically proficient being able to really quickly start these servers up and share the instructions with friends, family members, and fellow activists,” Lund says. “So you can take the instructions you’re left with at the end of the setup process and give those to any number of people who can use those instructions to connect to the server and start routing their traffic through it.”

“This is an example of a package that can allow anyone to get around most types” of control, says Joseph Lorenzo Hall, the Chief Technology Officer at the Center for Democracy and Technology.

“That’s the kind of stuff—it’s not usable by ‘normal people,’ so to speak—but if you have any technical ability, it’s a freaking revelation,” Hall adds. “That’s the kind of stuff we’re going to have to develop more of: Things with no business involvement, so there’s no one to get legal jurisdiction over to force them to do stuff, and using secure open-source software that’s easy to build and cheap to replicate.”

Using Streisand—where everything is open-source, the server is isolated, and the operator can be known personally to the user—means one can avoid commercial VPN services, which tend to operate on the basis of big promises—internet traffic private from all—but little transparency and verification of the security reality on which they operate.

“The promise of the internet as something that can connect people across vast differences and expose people to new ideas is really important to me.”

Streisand is not a marquee project. It’s had a slow but steady path toward its users since the day it was launched in mid-2014. It’s relied in large part on the kind of quiet and deliberate game of whispers that so often moves powerful privacy tools into the hands of people who need them. In countries like China that so thoroughly monitor and censor social media, it’s these trusted one-to-one messages that effectively spread anti-censorship software.

“It’s hard to say how many users it has,” Lund says of Streisand. There is no tracking in the software by design, so there is no precise way for him to know who is using his hard work. “But I get the impression that it’s helping people. I find that really satisfying.”

Success stories from China—a notorious theater of censorship that was at the front of Lund’s mind when he launched Streisand—suggest that the sharing model is in play. In Shanghai, one user reported a server with over 1 TB of data per day running clear through the Great Firewall.

“That felt really good because the server that this one user had set up was helping probably hundreds of people,” Lund says.

https://twitter.com/stijlist/status/768334993336700928

If the specters of Turkey and China inspired Stresiand, a strong Westward creep of internet surveillance and control is pushing Lund’s work now. Recent momentum toward bulk data collection and control in the U.K. as well as officials in Germany and France pushing to poke holes in strong encryption has privacy activists wondering what will happen in the United States next.

“I want to do everything I can,” Lund says, “to make sure the line doesn’t keep moving.”