The issue of stop-and-frisk was an unexpected focal point of the presidential debate on Monday. Donald Trump and moderator Lester Holt sparred over the constitutionality and success of the controversial policing strategy.

In response to a question posed to both candidates about healing the racial divide, Trump called for a return to “law and order,” a promise he’s repeated several times on the campaign trail. Trump then discussed violence—not race relations—in inner cities, focusing on Chicago instead of Charlotte, Baton Rouge, or any of the other cities impacted by police violence in recent years. Trump proposed bringing back the practice of stop-and-frisk to Chicago.

Here are Trump’s comments about stop-and-frisk from Monday:

We have a situation where we have our inner cities, African- Americans, Hispanics are living in hell because it’s so dangerous. You walk down the street, you get shot.

In Chicago, they’ve had thousands of shootings, thousands since January 1st. Thousands of shootings. And I’m saying, where is this? Is this a war-torn country? What are we doing? And we have to stop the violence. We have to bring back law and order.

In a place like Chicago, where thousands of people have been killed, thousands over the last number of years, in fact, almost 4,000 have been killed since Barack Obama became president, over — almost 4,000 people in Chicago have been killed. We have to bring back law and order.

Now, whether or not in a place like Chicago you do stop-and-frisk, which worked very well, Mayor Giuliani is here, worked very well in New York. It brought the crime rate way down. But you take the gun away from criminals that shouldn’t be having it.

We have gangs roaming the street. And in many cases, they’re illegally here, illegal immigrants. And they have guns. And they shoot people. And we have to be very strong. And we have to be very vigilant.

We have to be — we have to know what we’re doing. Right now, our police, in many cases, are afraid to do anything. We have to protect our inner cities, because African-American communities are being decimated by crime, decimated.

Holt then countered that stop-and-frisk was actually ruled as unconstitutional in New York City, contrary to Trump’s statement that it “worked very well.” Trump then insisted that Holt was wrong.

Here’s the full exchange:

HOLT: Your two — your two minutes expired, but I do want to follow up. Stop-and-frisk was ruled unconstitutional in New York, because it largely singled out black and Hispanic young men.

TRUMP: No, you’re wrong. It went before a judge, who was a very against-police judge. It was taken away from her. And our mayor, our new mayor, refused to go forward with the case. They would have won an appeal. If you look at it, throughout the country, there are many places where it’s allowed.

HOLT: The argument is that it’s a form of racial profiling.

TRUMP: No, the argument is that we have to take the guns away from these people that have them and they are bad people that shouldn’t have them.These are felons. These are people that are bad people that shouldn’t be — when you have 3,000 shootings in Chicago from January 1st, when you have 4,000 people killed in Chicago by guns, from the beginning of the presidency of Barack Obama, his hometown, you have to have stop-and-frisk.

So who’s right? Let’s set the record straight on stop-and-frisk. Here are six myths about stop-and-frisk, debunked.

Myth 1: Stop-and-frisk is unconstitutional

It’s true that the Fourth Amendment protects Americans from unreasonable stop and seizures by law enforcement without a warrant. But if police officers have reason to believe that you’re armed and dangerous, the Supreme Court found they are constitutionally within their right to “stop-and-frisk” or pat you down. The Supreme Court ruled that the practice of stop-and-frisk was constitutional in a 1968 decision known as Terry v. Ohio.

According to the ACLU, the Terry decision set a precedent that allowed officers to interrogate and frisk suspicious individuals without probable cause for an arrest. There’s one caveat, though: Police must articulate a reasonable basis for the stop.

“Stop-and-frisk, when applied according to the Supreme Court rulings, is constitutional,” said Professor David Weisburd, the director of the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy at George Mason University, in an email to the Daily Dot. “The problem is that you cannot use stop-and-frisk as a method of crime control unless you are only stopping people who meet the constitutional threshold.”

Meeting the constitutional standard was something New York City’s police officers simply weren’t doing. In 2013, a ruling by Judge Shira A. Scheindlin of Federal District Court in Manhattan found that NYPD officers had been systematically stopping innocent people without cause for years. The NYPD was also stopping young black and Hispanic men in highly disproportionate numbers. A 2008 statistical study of nearly 4.5 million stops in New York City showed that 83 percent of the people stopped were black or Hispanic, according to the New York Times.

So not only did the NYPD’s approach to stop-and-frisk ignore constitutional protections against unreasonable search and seizure, it also ignored the 14th amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Myth 2: Stop-and-frisk “worked very well” in New York City

The NYPD’s increased practice of stop-and-frisk over the Bloomberg administration was widely reviled by the city’s residents and the target of three federal lawsuits.

The New York Times interviewed 100 people in 2012 about their experiences being stop-and-frisked. Some people spoke about being talked to like they were “ignorant” or “an animal.” Others reported more polite interactions. Many felt like they were stopped by police for no reason outside their race. The incidents had a lasting impression on the individual’s trust of the police force.

“They’ll ask, ‘Where are you headed?’ When you’re African-American, you have to have a definite destination. Everyone else can just say, ‘Mind your own business,’” Al Blount, a minister from a church in Harlem, told the Times.

One reader wrote to the Times: “I’m a high school teacher in a poor section of the Bronx (Tremont), and nearly all of my male students have been stopped and frisked at some point.”

New York City first began collecting extensive data on stop-and-frisk, which included specifying the reason each person stopped as well as their age and race, in 2002. At the same time, a public safety initiative by newly minted Mayor Michael C. Bloomberg put an emphasis on stop-and-frisk. The end-result? According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, annual stops rose from 97,296 incidents in 2002 to 685, 724 stops in 2011.

Of all the people stopped by the NYPD between 2003 and 2013, roughly 10 percent were white, according to the ACLU. Roughly 41 percent of those stopped were young black and Hispanic men, who accounted for 4.1 percent of the city’s population. Nearly nine out of 10 encounters of those encounters with young black and Hispanic men stopped were found innocent. Furthermore, stop-and-frisk incidents involving minorities were more likely to involve the use of force.

Of the nearly 2.5 million frisks conducted by NYPD over the decade of 2003-2013, only 2 percent ended in finding an actual weapon.

Myth 3: Stop-and-frisk went before a judge in New York City, but the case was thrown out

After Judge Scheindlin ruled in a class-action lawsuit that the NYPD’s use of stop-and-frisk had violated the Constitution and resulted in “indirect racial profiling,” things quickly got ugly.

Mayor Bloomberg accused Scheindlin of being biased against police and claimed Scheindlin had encouraged plaintiffs to steer the case, known as Floyd v. City of New York, into her courtroom.

But Bloomberg’s tactics didn’t work. A federal appeals court in November 2013 denied a request from the city’s lawyers to overturn Scheindlin’s ruling. Mayor Bill de Blasio, who campaigned on a promise to put an end to stop-and-frisk, took office in January 2014 and agreed to withdraw the city’s appeal of the stop-and-frisk case and accept the reforms proposed by Scheindlin.

“We’re here today to turn the page on one of the most divisive problems in our city,” Mr. de Blasio said at a news conference following the announcement, according to the Times. “We believe in ending the overuse of stop-and-frisk that has unfairly targeted young African-American and Latino men.”

Myth 4: Stop-and-frisk brought crime down in New York City

“That is a very hard-to-answer question,” said Professor David Weisburd, who has led studies of stop-and-frisk incidents in New York City and their impact on crime, in an email to the Daily Dot.

Crime in New York City is very concentrated, according to Weisburd. Just 5 percent of New York City’s streets produce 50 percent of the city’s crime. Not surprisingly, stop-and-frisk incidents were largely delegated to high-crime areas.

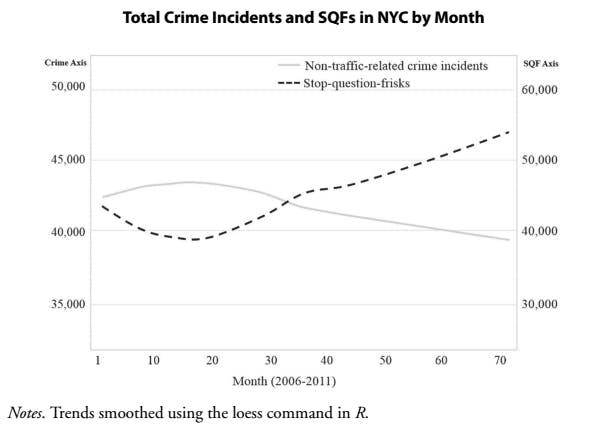

Weisburd and his team looked at the total number of crimes and stop-and-frisk incidents in New York City per month between the years 2006 through 2011. They found that as the number of frisks increased, the number of crime incidents decreased.

Weisburd said that while the findings showed that stop-and-frisk did have a deterrent impact on crime in New York City, the overall impact was not large—probably in the range of a decline of 2 percent during the peak of stop-and-frisk in New York City.

“The public and some commentators are looking for a simple answer to the stop-and-frisk question,” Weisburd wrote. “They want it to be either all good or all bad. The problem is, is that there is reason to believe that stop-and-frisk incidents do deter crime. Focused on very high-crime violent streets, there is also experimental evidence that stops reduce crime levels.”

But Weisburd added that the gains of stop-and-frisk don’t negate the fact that it’s an intrusive policing approach and can negatively impact the lives of the people stopped and their communities.

“My own take on this is that we should simply acknowledge that SQFs reduce crime,” he said. “At the same time, there may be other ‘softer’ tactics that can have similar impacts when focused on the small number of streets in the city that are crime hots spots.”

Cutting back dramatically on stop-and-frisk hasn’t affected crime in New York City. In fact, there were 131 more murders at the peak of stop-and-frisk in September 2011, when stop-and-frisk was at its peak, the New York Police Department tweeted out in a statement.

The NYPD just sent out this fact check to city residents on yesterday’s presidential debate pic.twitter.com/FNyRcEYUS5

— Oliver Darcy (@oliverdarcy) September 27, 2016

Myth 5: Chicago does not practice stop-and-frisk

Virtually every police force in America practices some form of stop-and-frisk. Former New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton told The New Yorker that stop-and-frisk was an essential police tool.

“Stop-and-frisk is such a basic tool of policing. It’s one of the most fundamental practices in American policing. If cops are not doing stop-and-frisk, they are not doing their jobs,” Bratton said.

But numerous reports of racial discrimination and abuse has lead to many cities scaling back their efforts. Reforms against racial profiling in the use of stop-and-frisk are being implemented in Boston; Newark, New Jersey; Cleveland; and Minneapolis.

More cities are taking a page from New York City’s book and collecting racial data on stop-and-frisk incidents. Philadelphia, which settled a class-action lawsuit over its stop-and-frisk practices in 2011, revealed that more than a third of its stops last year were made without reasonable suspicion. A total of 69 percent of stops in Philadelphia in 2015 were of black residents.

Stop-and-frisk incidents fell by 80 percent in Chicago in 2016, following a new policy that requires police to fill out a two-page report after each incident. Meanwhile, the murder rate in Chicago is up by 50 percent this year. The city recorded its 500th murder following a spate of gun violence over Labor Day weekend that ended in 13 deaths. Chicago Police superintendent Eddie Johnson said the surge in murders in Chicago are due to an increase in gang violence and weak gun laws.

Chicago police say there’s no reason to believe the decrease of stop-and-frisk incidents is linked to the surge in murders, at least for now.

Myth 6: Murder in the U.S. is on the rise

It’s true that murders in the United States jumped by 10.8 percent in 2015, according to statistics released this month by the FBI. That’s the largest spike in the murder rate since 1971. But such a statistic is misleading, considering that the number of murders in 2014 was historically low. There were an estimated 14,164 people murdered in the United States 2014, the lowest in nearly five decades.

“If you think about it, murder rates have been driven so low, in a sense, the only way to go is up,” explained Dr. James Fox, a criminology professor at Northeastern University to Vice. “The lower you get, the more likely you are to get a rebound.”

2015 saw a dramatic spike in the number of murders across 35 major cities due to gang and gun violence. Cities like Milwaukee, St. Louis, Baltimore, New Orleans, and Chicago topped the list of murders. Meanwhile, a total of 344 homicides in Baltimore made 2015 the deadliest year in its history. There were an estimated 15,696 murders nationwide in 2015, which is roughly the same as 2009.

The murder rate is projected to increase by 13 percent in 2016, according to experts at the Brennan Center for Justice. More than half of that uptick is due to an increase in violence in Chicago, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. According to the Brennan Center, however, there’s little evidence to suggest that the dramatic increase in murders in those cities foreshadow a larger trend nationwide.

These serious increases seem to be localized, rather than part of a national pandemic, suggesting that community conditions remain the major factor. Notably, these three cities all seem to have falling populations, higher poverty rates, and higher unemployment than the national average. This implies that economic deterioration of these cities could be a contributor to murder increases.

The murder rates in New York City and Los Angeles are still at historic lows.