With 3G fading into a distant memory, consumer devices finally have two feet planted firmly in 4G territory. What was once a carrier buzzword, sometimes sold as a fib, is now de rigeur for smartphones and tablets… but what’s next?

What is 5G?

Like 3G and 4G before it, 5G is a set of mobile standards. Basically that means that 5G technology will be defined as anything that falls within those parameters, which mostly pertain to speed. For example, LTE is the most common flavor of 4G mobile connection, though a competing standard known as WiMAX and HSPA+ were also (arguably) categorized as 4G, though are now considered mostly precursors to true 4G LTE networks.

With the rise of video sites like YouTube, and other multimedia-heavy social platforms, data consumption has grown exponentially. Part of the challenge of 5G networks will be to balance voracious data consumption with network limits, battery life, and the cost of providing such a service to begin with.

According to the 5G Innovation Centre, a group headquartered at the University of Surrey that specializes in mobile networks, “[5G] will need to offer far greater capacity and be faster, more energy-efficient and more cost-effective than anything that has gone before.

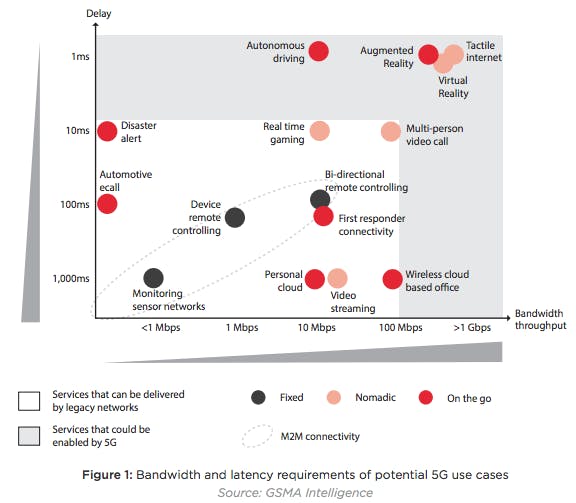

In the future, many applications—from advanced gaming to driverless cars—will require much shorter network response times to enable very rapid reactions.”

What will we use it for?

Striking that balance will have potentially huge implications in the Internet of Things—the term coined for everything from smarthomes to self-driving cars and ingestible sensors. Once everything is connected, we’re going to expect all of our devices—not just our smartphones and computers—to communicate immediately and fluidly. As more devices flicker online, the burden on wireless networks to shoulder all of that device chatter will reach unprecedented new heights. As companies like Google and Facebook are racing to enable global Internet connectivity, markets in the developed world have pushed into use cases we couldn’t have dreamed up five years ago. The rise of virtual reality, persistent virtual worlds requiring persistent connections, is one example.

As described by the 5G Innovation Centre, the key to 5G will be cleverly optimizing network connections to make use of the tech that’s out there, balancing patterns in user behavior—peak use times when everyone streams a Netflix premiere, for example—with the resources available. That challenge isn’t new, but it’s something anything in the running to be called a 5G network will need to tackle.

Ericsson, a mobile company that’s already been flexing its 5G muscle, is shooting to have such a system ready by 2020. In a lab test last year, Ericsson hit the 5 gigabits per second (Gbps) mark, though lab conditions are generally far closer to ideal than real-life tests.

For comparison, a typical 4G LTE speed on Verizon hovers around 33 megabits per second (Mbps) in late 2014. For a sense of how quickly our expectations for mobile data speed shot up, in 2013, 4G LTE download speeds in New York City averaged just 6.7 Mbps—and it probably felt pretty fast back then, too.

According to Ericsson, 5G networks will need to hit 10 Gbps peak speeds, with 100 Mbps speeds as a reachable goal in most non-rural settings. Due to the high stakes nature of the devices that will be cruising along on future mobile networks—think traffic lights, front door locks, and biotechnology—networks should aim to reduce latency to less than 1 millisecond (ms).

Latency refers to the amount of delay time it takes for a device to communicate to a network and it’s the real-world confounding variable that makes the sort of ideal speeds mobile companies can achieve in a lab setting mostly impossible in a real world settings full of literal and figurative barriers between devices and mobile networks. According to Ericsson:

“…. 5G will also provide wireless connectivity for a wide range of new applications and use cases, including wearables, smart homes, traffic safety/control, and critical infrastructure and industry applications, as well as for very-high-speed media delivery.

In contrast to earlier generations, 5G wireless access should not be seen as a specific radioaccess technology. Rather, it is an overall wireless-access solution addressing the demands and requirements of mobile communication beyond 2020.”

How far off is it?

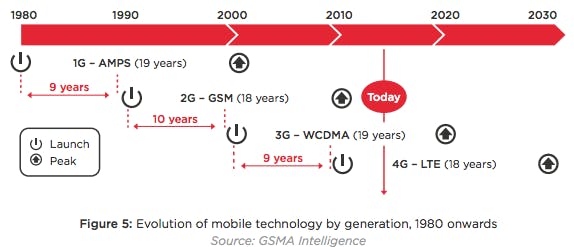

There isn’t a whole lot yet set in stone about 5G, but 2020 is the common target date for the advent of 5G. Still, 4G is alive and well, and won’t even hit peak saturation until after that date, according to a mobile report by GSMA Intelligence.

How fast is it?

Really fast, though how fast is still a matter of debate. While some 5G consortiums propose a peak speed of 10 gigabits per second, groups like the EU are more focused around the way that 5G might allow devices to remain “continuously connected in challenging situations like train journeys [and] very dense or sparsely populated areas.”

According to GSMA Intelligence, some proposed guidelines include:

1-10Gbps connections to end points in the field (i.e. not theoretical maximum)

• 1 millisecond end-to-end round trip delay (latency)

• 1000x bandwidth per unit area

• 10-100x number of connected devices

• (Perception of) 99.999 percent availability

• (Perception of) 100 percent coverage

• 90% reduction in network energy usage

• Up to ten year battery life for low power, machine-type devices

Still, it’s worth emphasizing just how many groups are proposing differing sets of standards right now. The E.U., 5G Public Private Partnership (5GPPP), Next Generation Mobile Networks Alliance (NGMN), and the 5G Innovation Centre—not to mention individual mobile companies like Samsung, Ericsson, and Nokia—all have different ideas about what 5G might look and function like.

What are the challenges?

For one, defining what 5G means at all. A number of groups cobbled together from mobile industry players are working toward a definition of 5G, but for a standard to really be set, they’ll have to all agree. We saw this all hashed out with 4G, which began as a marketing lie (remember the debates over HSPA+ and that little “4G” symbol popping up on not-so-4G iPhones?) and worked its way into the robust, prevalent mobile network standard known as LTE.

Beyond setting a standard to begin with, the challenges are everything that afflicts today’s 3G and 4G connections, multiplied by next generation expectations of speed and the low latency that’s necessary to enable a true Internet of Things.

Right now, to hit 5G-like speeds in lab settings, Nokia is employing “highly directional antennas” that focus a beam in order to maximize its potential speed. But this sort of cheat has its own set of problems: A device moving around has a harder time maintaining a connection with this sort of narrow, focused connection.

The industry may have a solid five years to work these kinks out, but considering the scope of what we’re setting up a 5G standard to describe, it better hurry up.

Illustration by Max Fleishman