In a sense, absurdly-tweeting Senator Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) was right: the Cybersecurity Act of 2012 (CSA), which the Senate voted down yet again Wednesday, is “a little bit like the movie Groundhog Day.”

In other words, it’s the second time that the CSA was defeated in the Senate. Meant to address the U.S.’s reportedly dire need for stronger protection from cyber attacks, its provisions still give privacy advocates a number of concerns. It even lost a backer since the last vote in August. Now at 51-47, it was far from the 60 votes necessary to pass.

It was the same old arguments from both the CSA’s supporters and detractors. Supporters of the bill, like Susan Collins (R-Maine), compared cyber attacks on American infrastructure to a “cyber 9/11” and “digital Pearl Harbor.”

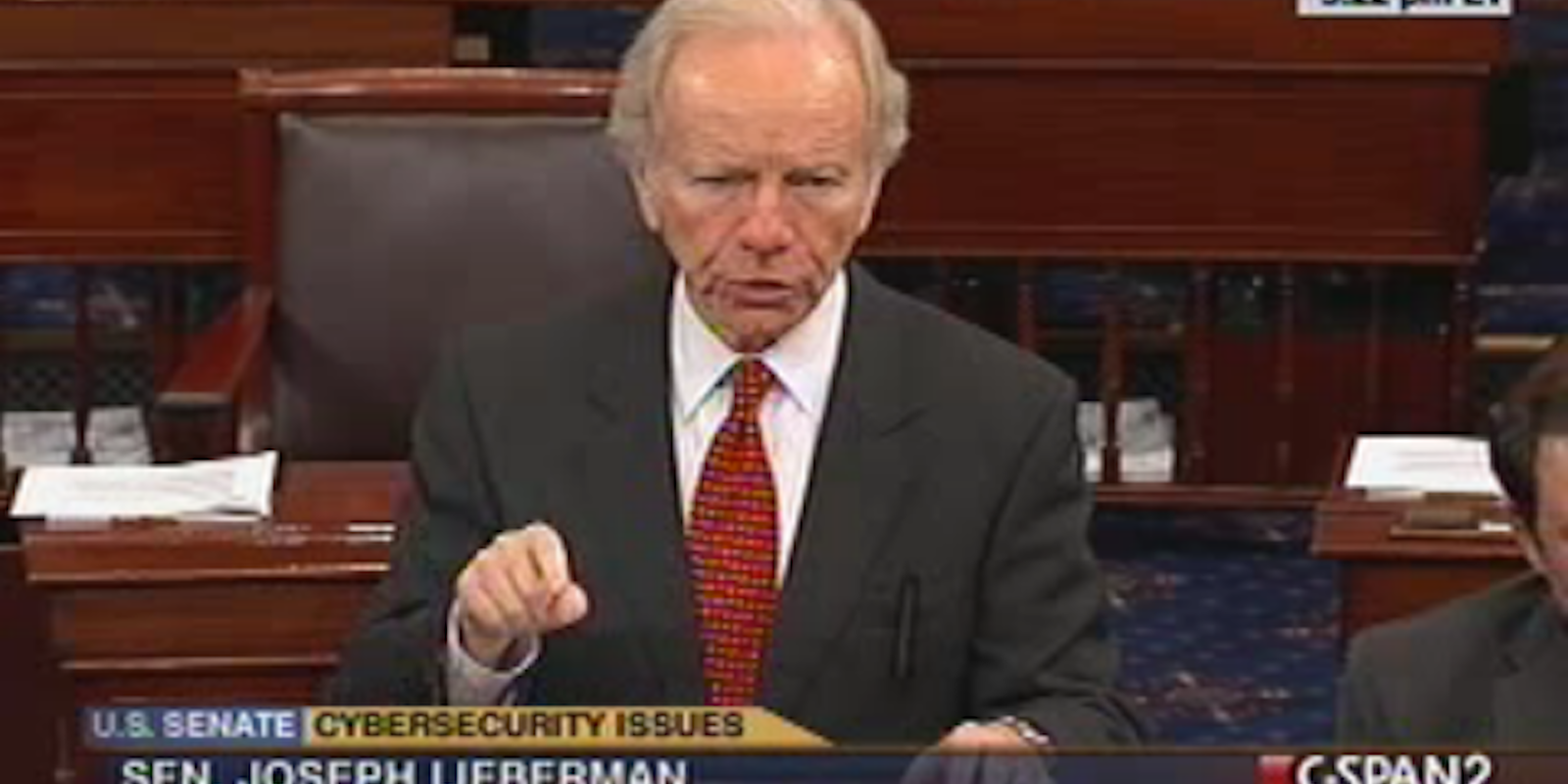

Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.), who authored the bill, said, “our cyber enemies are at the gates. They’ve broken through the gates.”

Meanwhile, opponents like Grassley decried it, largely for not being the Cyber Intelligence Security Protection Act (CISPA), which would make it easier for government agencies to access any network that’s under attack. The drawback to that plan, for privacy advocates, is that citizens’ private files are then in the government’s possession.

President Obama has repeatedly threatened to issue an executive order on cybersecurity if Congress doesn’t agree on one, which now seems to clearly be the case.

“What an unfortunate thing,” said Senate majority leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.). “Cybersecurity is dead for this Congress.”

That might be a good thing, or at least the lesser of two evils, when it comes to protecting your privacy, though. While every proposed cybersecurity bill has rankled advocates to some degree or another, Obama’s executive order, which is based on the CSA, is said to contain at least some privacy protections.

Specifically, the executive order would (in its current form, which is subject to change) make a clear distinction between what counts as critical infrastructure—power grids, railroad systems—and social networking, like Facebook and Google search history. Tougher controls can apply to the former while leaving the latter alone. At least one senator with a history of Internet advocacy, Ron Wyden (D-Oreg.), has a history of pushing for such a distinction, and, as the CSA never actually made it, voted against the CSA both times.

Image via C-Span