U.S. and European negotiators are racing to complete a data-sharing agreement that American businesses say is crucial to their overseas operations. But in the wake of the court ruling that struck down the old agreement, no one knows how to solve the pressing privacy concerns at the heart of the debate.

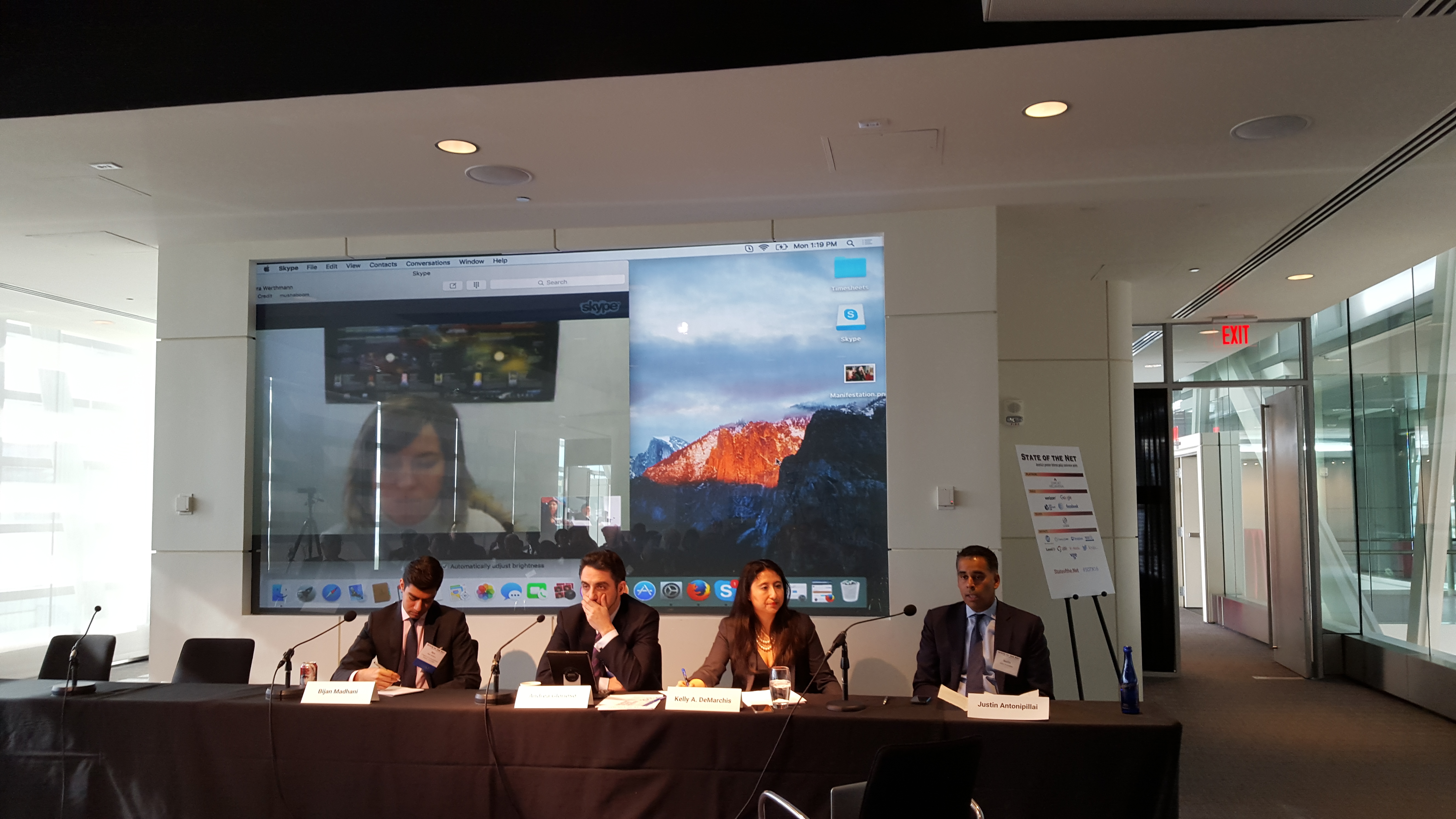

Negotiations over a new “Safe Harbor” deal—which would let American companies transfer European citizens’ data to and from their U.S. servers—prompted conversation, speculation, and no small amount of anxiety at the Internet Education Foundation’s annual State of the Net conference on Monday in Washington, D.C.

Attendees heard first from Max Schrems, the Austrian man whose lawsuit challenging Facebook‘s U.S. storage of his personal data led the European Court of Justice to invalidate the first Safe Harbor agreement. The 15-year-old deal had allowed American companies to “self-certify” that their handling of user data met European regulators’ stringent privacy standards. But the ECJ ruled that, because U.S. companies were subject to the far-reaching mass surveillance programs revealed by Edward Snowden, they could not credibly claim to be keeping user data private and secure.

The U.S. Department of Commerce and the European Commission are hard at work on a new Safe Harbor deal, but privacy advocates, including Schrems, aren’t sure how it can possibly survive ECJ scrutiny without fundamentally reforming U.S. surveillance practices. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) requires “electronic communications service providers” to comply with many of the programs that Snowden revealed. Because FISA is not likely to change any time soon, Schrems said, “I don’t really see a solution.”

Google, Facebook, and other companies that store user communications have pressured the Commerce Department to quickly reach a deal that will preserve their ability to “self-certify” compliance with E.U. privacy standards. The data-protection regulators of many European nations have warned that they will begin to enforce their stringent privacy rules at the beginning of February. Without a new Safe Harbor, U.S. companies’ routine business operations could expose them to fines and other penalties under those rules.

At a panel discussion on Monday, Justin Antonipillai, the Department of Commerce’s deputy general counsel and a member of the U.S. negotiating team, expressed confidence that the two sides would reach an agreement. But he noted, “Time is not on our side.”

One of the key issues in the negotiations is how E.U. citizens will be able to challenge the American government over its handling of their private data. Antonipillai, who called the Obama administration’s latest proposal “one of our best offers,” added that any deal would have to acknowledge the role that the Federal Trade Commission plays in enforcing consumer-protection laws in the U.S.

In his response, Andrea Glorioso, a member of the E.U. delegation in Washington that is negotiating the deal, offered an indication of why this issue remains tricky for two sides with dramatically different regulatory structures.

While Glorioso said he had “deep respect” for the FTC‘s work, he noted that the commission’s status as an independent agency complicated things. Because the president cannot order the FTC to take up a particular complaint, European officials are not content to let the commission serve as the only cop on the beat. They want to be able to exert pressure on the White House to take their citizens’ complaints seriously.

Glorioso said that negotiators were considering how the U.S. government could redress Europeans’ complaints outside of the FTC, possibly through the Commerce Department, but he emphasized that the E.U. delegation has “not asked for legislative changes” to the way the U.S. handles such complaints.

Both Schrems and members of the panel that followed his talk agreed that the new Safe Harbor deal could not and would not resolve the broader debate over the proper extent of government surveillance.

Schrems said that he wanted to see the European Court of Human Rights settle the issue eventually; the privacy of citizens’ personal data is considered a fundamental right in Europe. The high courts of E.U. member states will have to address that matter first, though. In the meantime, Glorioso called the larger surveillance debate “a conversation that needs to happen.”

Photos by Eric Geller