A group of Russian youth loyal to President Vladimir Putin has found a new mission: discover and report online “gay propaganda” to the government.

Russia has severely cracked down on homosexuality in recent years, and openly gay citizens face physical danger. The situation is amplified by the so-called “blacklist law” of 2013, which empowers the state watchdog, Roskomnadzor, to censor content that allegedly promotes self-harm, drug use, or even gay behavior among people under 18. All it takes is a formal request, and Roskomnadzor is compelled to investigate. If it finds a claim has merit, it can take its subject to court.

Enter the Young Guard. Founded in 2005 as part of Putin’s “United Russia” party, the pro-Kremlin movement aims to unite Russian youth and involve more people into the social-political life of the country—in other words, to engage young voters, especially those who live in the country’s more remote regions.

A spinoff group, called the Media Guard, has honed in on a niche purpose: using the Internet to fight homosexuality.

In recent years, however, a spinoff group, called the Media Guard, has honed in on a niche purpose: using the Internet to fight homosexuality.

That direction crystallized in 2014, with Media Guard youngsters’ war against an LGBT support movement called Children-404. Named after the iconic “not found” Internet error message, the movement’s name nods to the idea that the Russian government pretends young LGBT citizens don’t exist. Children-404 exists as a website and as communities on Facebook and its Russian equivalent, VKontakte (VK), which give Russian LGBT youth places to vent and anonymously get help from psychologists and lawyers.

In December, Roskomnadzor commissioned psychological scientist Lidya Matveeva to study Children-404. The results were dire for the group: Her report referred to homosexuality as a “sin” and a “pathology,” and she used the Bible as a literary reference. Citing Matveeva’s findings, Roskomnadzor sued Children-404 founder Elena Klimova, saying she broke Russia’s law against promoting homosexual attitudes to children. Klimova lost, then lost her subsequent appeal, though she’s trying to appeal again. She claims collusion between Roskomnadzor and the Young Guard, saying her court appearances drew angry protesters from the Young Guard, though her court dates should have been secret.

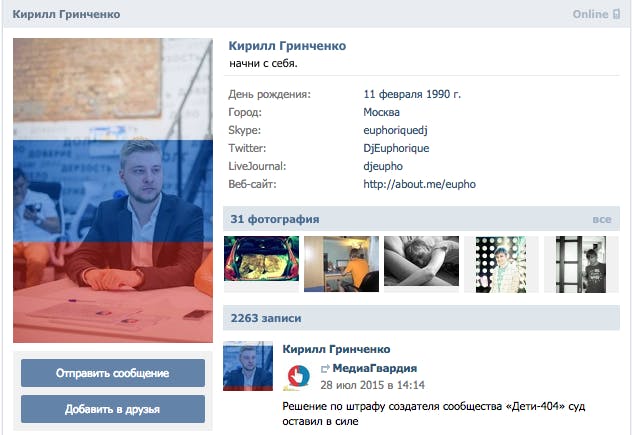

In July, anticipating Kilmova’s appeal trial, the Media Guard started collecting petition signatures on Avaaz.org to block Children-404’s VK presence, hoping to eventually present the full list to Russia’s Prosecutor General. About two weeks later, when it had reached around 5,000 signatures, organization spokesman Kirill Grinchenko bragged of its growing popularity, saying that “Each of [the signatories] made his contribution to the protection of minors from LGBT propaganda.” When some questioned whether all the names on the petition were legitimate, Grinchenko dismissed the conspiracy as “not true,” though Avaaz deleted the petition the next day.

On July 28, Roskomnadzor called the Media Guard’s ranking member as a witness against Kilmova and used the group’s complaints as evidence. Kilmova got a ?50,000 ($820) fine.

But the kids had already moved on to other targets. A month earlier, Bryansk senator Mikhail Marchenko had suggested that Roskomnadzor could “send recommendations to social networks on how they must work in Russia.”

Marchenko was concerned primarily with emoji, the little faces users make with punctuation marks. “These emoticons with non-traditional sexual orientation are visible to all users of social networks, most of which are minors. But the propaganda of homosexuality is prohibited both by law and by traditional values that exist in our country,” Marchenko said.

The Media Guard had their next target.

Visitors to the Media Guard VK page now see members embroiled in an investigation of whether emojis can constitute homosexual propaganda. They’re particularly critical of Apple’s same-sex parents kissing emoji, introduced in April. It could run afoul of a law prohibiting any information denying family values, promoting non-traditional sexual relationships, and forming disrespect for parents and other family members.

There isn’t yet legal precedent, even in Russia, for prosecuting technology companies for promoting a gay agenda through emojis. But that seems to be where the country is headed.

Illustration by Jason Reed