To capture the spirit of a bygone Web, Rooms, Facebook’s newest app, erects an Escherian stairwell. Descending into its particular, labyrinthine abyss, in short order you will encounter two of the most inevitable virtual populations around: 1) people who want to have sex and 2) people who are unhappy.

Like most hot new social apps, Rooms serves one of those groups well and throws the other to the wolves—guess which is which.

Lonely Rooms

Beyond a tiny cluster of initial built-in Rooms, all of the app’s virtual communities are user-generated. They’re totally random; from Slopestyle (it’s a snowboarding thing) to a Room that “showcases photographs of cool shoes in cool places” to Gay Videos (NSFW) to Debate 90’s NBA. So far, most are for niche interests (often really, really niche interests).

Top 10 Rooms – Number 3 – Depression Support #depressionsupport #rooms #roomsapp #facebookrooms #toptenrooms pic.twitter.com/thLgJnrDvV

— Facebook Rooms (@FacebookRooms) November 4, 2014

Rooms lead developer Josh Miller has been tweeting the QR codes of Rooms communities as he encounters them, promoting the Depression Support room shortly after Rooms launched. The Rooms blog promoted it too, in a top 10 list with this commentary:

Although we’ve seen many people use Rooms to discover new people who share their interests, sports, or hobbies, we’ve seen others use it to build “support rooms”—safe spaces for discussing sensitive topics.

In this room, almost 200 people are seeking advice, trading stories, and finding support among others who suffer from illnesses like depression and bipolar disorder.

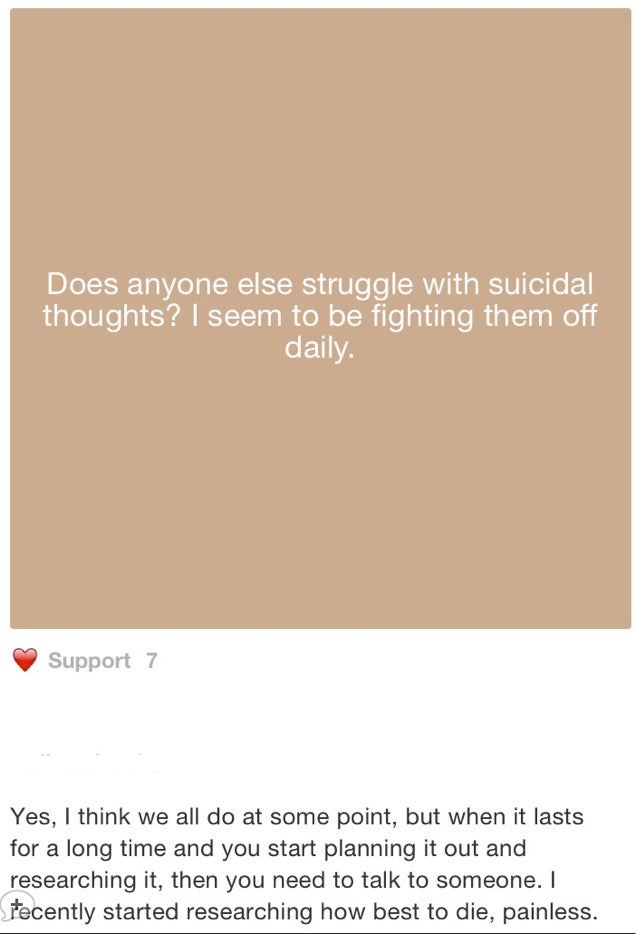

The problem is that pseudo-anonymous social apps like Miller’s don’t have any idea how to handle mental health. In theory, users help themselves by sharing their dark thoughts and help each other by brightening things up with empathy. Unfortunately, mental illness—even depression, which is pretty well understood—doesn’t work like that.

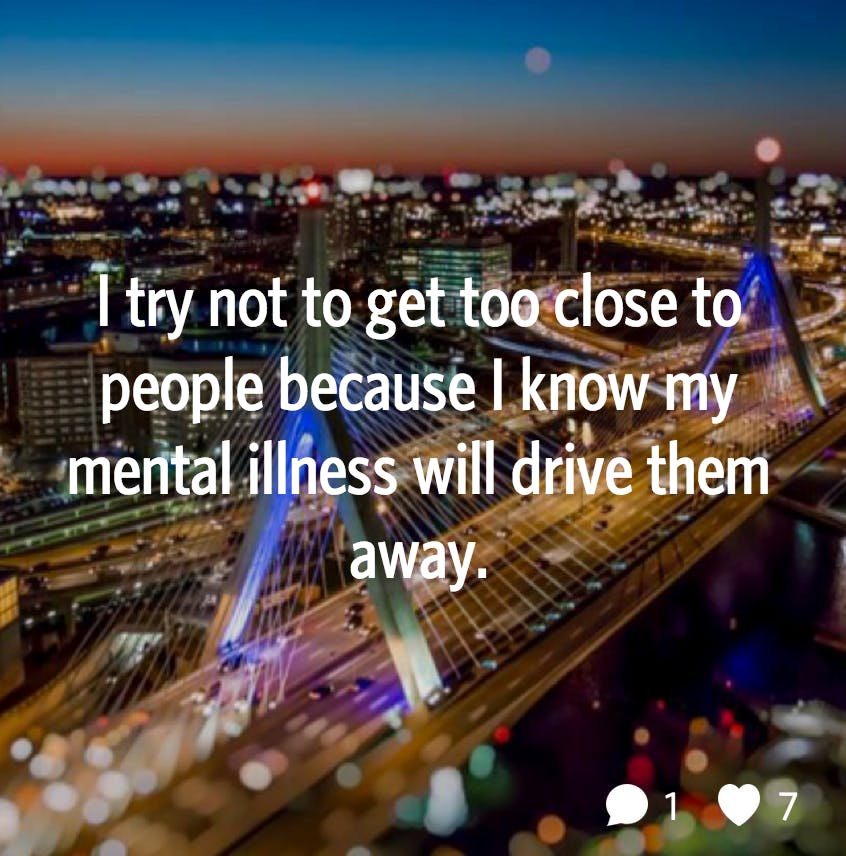

In the in-no-way official Depression Support room, user reluctantmom posted a notecard that reads “suicide doesn’t take away the pain, it gives it to someone else.” The post has nine hearts—rooms all have custom emoji versions of the like button—and two comments. Moderator redheadrocker responded, darkly, “That’s what kept me from doing it, my kids.” User Sergeant posts “Anyone here with combat PTSD?” (Apparently not.) In a Room called Mental Health Forum (19 members), a post invites members to share their triggers—“Some may be more common than you’d expect!”

The conversations fracture off when two like minds find one another. “Depression Support” boasts 227 members. A newer mental health themed Room called “OCD Support” is 14 members strong. A Room dedicated to “Removing the Stigma” of mental illness has seven members and five posts, four of which are meme-like images repeating the name of the room. “OCD Support” also links to “Struggling New Moms,” “Anxiety Disorders,” and “Depression Support.”

Rooms splinter off of one another endlessly. If the definition of insanity were “doing the same thing again and again expecting different results” (it’s not), the experience of searching for meaning, Room through Room, approaches something like that.

If you’re new to Rooms, “Depression Support” and its ilk sound like an official resource of some kind. But the well intentioned user-created forum was actually created by a young woman who appears to be trying to make sense of a close friend’s recent suicide. When it comes to serious mental illness, the blind can’t be left to lead the blind.

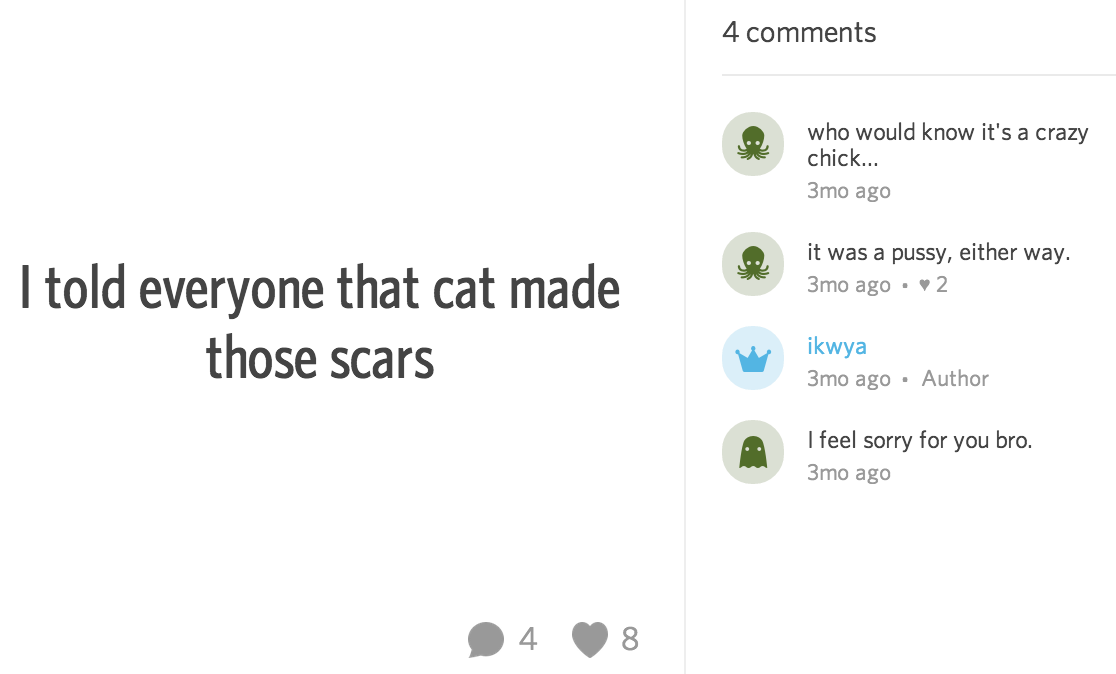

It might seem counterintuitive, but not everyone who suffers from mental illness benefits from the kind of community anonymous apps provide. In fact, when it comes to things like self harm and eating disorders (remember “pro-ana” sites?), casual sharing can incite competition and prove downright destructive.

Whisper to the rescue

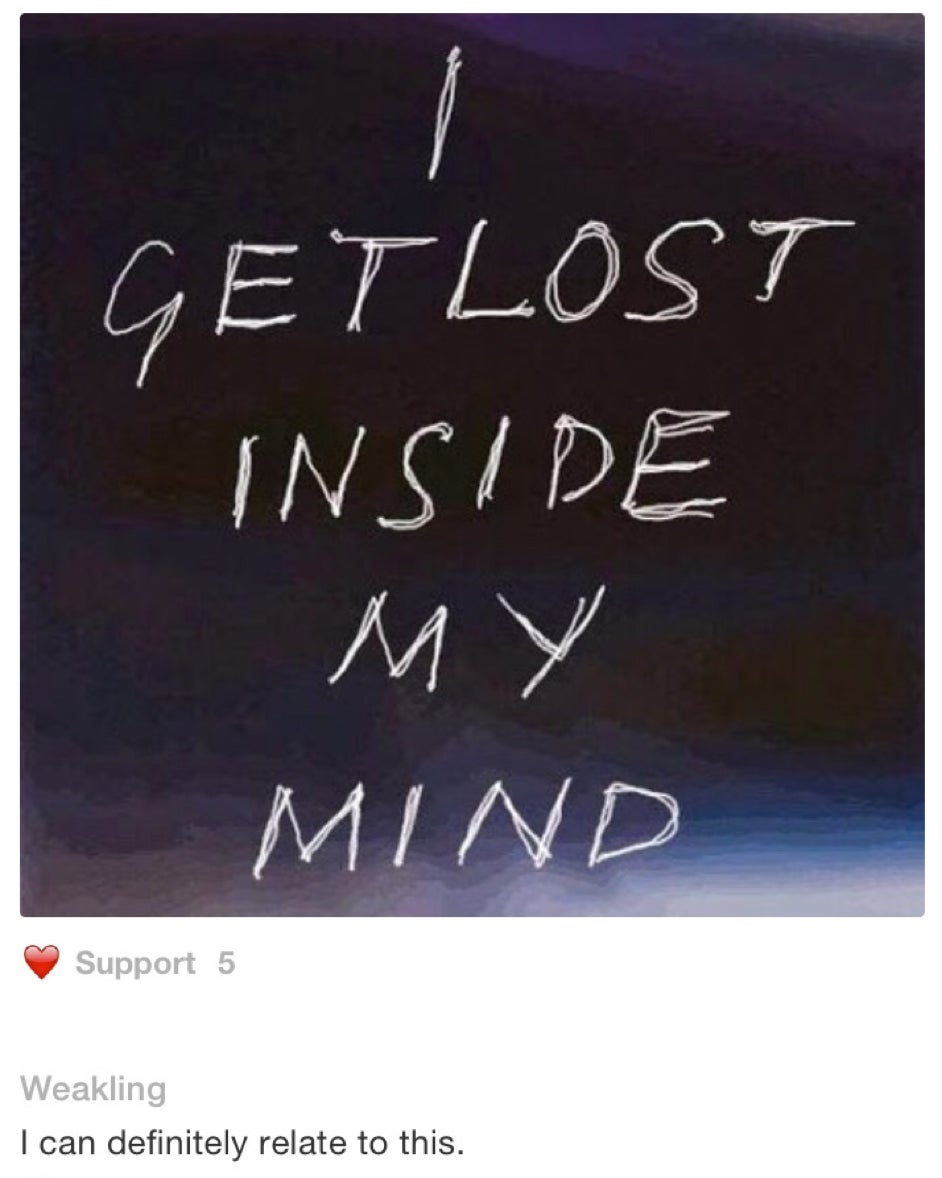

The same kind of dark stuff that pops up in the loose collection of nascent mental illness Rooms is commonplace on Whisper or Secret, where every other post is a straightforward gesture of loneliness if not a soul-crushing confession of some kind.

But if you want to kill yourself, never fear! Whisper cofounder Michael Heyward is here to boldly shoulder (and monetize) the burden of all that anonymous loneliness:

There’s an excess inventory of loneliness. The kid crying at night afraid to come out of the closet to his parents. Soldiers from Afghanistan with PTSD afraid of fireworks… I wanted to create a place that can show them they are not alone.

It’s not unusual for the tech community, steeped in hubris, to think it’s the first to any idea, but really? In reality, those places Heyward is talking about already exist and they’re curated by trained social workers, therapists, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Social apps with their eyes fixed on aggressive growth, venture capital, and all of Silicon Valley’s other shortcuts to a cash-glutted exit can’t cure PTSD, depression, or anything else. Nor is it appropriate for them to pretend to try.

Again, there is no scientific support that virtually hanging out with other depressed, anxious, or traumatized people on an anonymous app does anything consistently good. The bad, like sharing self harm techniques and triggers, is a widely observed and well documented phenomenon.

Whisper brags that it has referred more than 40,000 users to suicide hotlines, which is a good thing, though not one we can infer much from without more insight about the referral process and the kinds of posts that result in those referrals. Suicide, though tragic, isn’t by any means the only way to express the acute loneliness Heyward expressed concern about. Keeping people from killing themselves is good, but it’s a pretty low bar. Why not figure out how to make people happier?

Determined to sleep well at night, Whisper cofounders Heyward and Brad Brooks launched YourVoice, a website dedicated to its loneliest users. YourVoice is directed by Brooks’s wife, a licensed marriage and family therapist who espouses some new agey sounding insight about the “healing power in expressing your thoughts and feelings.”

On the staff page, no other practicioners with relevant licenses are listed, but big photos depict the Whisper cofounders next to two filmmakers. Roughly a third of the site is dedicated to curated, self congratulatory stuff like this:

YourVoice is difficult to navigate and at first just looks like a confessional video platform. To get to the stuff that actually helps people—hotlines, links to existing mental health resources—you’ll need to discover a hidden sidebar and click around a few times. Unlike anonymous social apps, the nonprofit organizations that YourVoice links to struggle to fund their important missions. Whisper’s $1 million feel good project is a hollow gesture that drummed up blindly positive press—and a pretty expensive one at that.

Secretly sad?

Secret is similarly delusional about its own exaggerated role in the well being of its users:

“We created Secret because we believe anonymity empowers people to share their deepest thoughts and to have honest conversations that can’t happen anywhere else.” A set of community guidelines discourages users from being horrible to one another—”Don’t bully, harass, threaten, demean, encourage self-harm, or promote any type of criminal activity.”

Unsurprisingly, Secret users are still totally horrible to one another.

Anonymish apps need to stick to knitting, nail art, and obscure music sub-genres. As cyber-harassment escalates on semi-anonymous platforms like Twitter and Tumblr, no one can seem to strike the right balance, creating new problems without addressing existing ones that aren’t lucrative.

If any of these social apps really wanted to help people suffering from depression, eating disorders, and other mental health epidemics, they’d at least build an easier way to connect users to specialists who can actually effect positive change. Have you ever tried to find a therapist online? Clogged with SEO-optimized junk sites, the process is arguably even worse now than it was 10 years ago. Organizations like the Trevor Project, which specialized in crisis intervention in the LGBT youth community, can reach users through social media, but the burden remains on them.

Social networks for people struggling with mental health exist already, but they weren’t built by Silicon Valley—they are staffed full time by volunteers answering hotlines and trained professionals matching treatment to symptom. When it comes to mental health, the tech community needs to sit down, shut up, and listen to the people who actually know how to help.

Photo via Valentina Costi (CC BY 2.0) | Photo via ryan melaugh (CC BY 2.0) | Photo via Benjamin Watson (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed