When the personal information of students and employees at Fairfax County Public Schools showed up on the dark web in October 2020, the Virginia school district had been in a standoff with hackers for nearly a month.

Even with help from the FBI, Virginia State Police, and a hired cybersecurity firm, the district admitted it couldn’t stop the hacker group known as Maze from making employees’ social security numbers available to the public.

But details of how the attack happened, and how much it ultimately cost taxpayers, are shrouded in secrecy. Fairfax County Public Schools has ignored a public records request the Daily Dot sent nearly two months ago, as well as over half a dozen phone calls and emails about the unacknowledged request, which it is required by law to respond to.

The documents in the Daily Dot’s request, which include emails, insurance policies, cybersecurity handbooks, and procurement contracts, could illuminate how hackers were able to penetrate the district’s systems and how much taxpayers have paid to recover from the attack.

Fairfax County isn’t the only district to keep these details hidden. Across the country, taxpayers have been left in the dark about how much school districts are paying after being hit by cyberattacks and ransomware.

The Daily Dot submitted public records requests to 15 school districts across the country that were hit by recent cyberattacks, including the one in Fairfax. But after over a month of negotiations, only six districts have agreed to disclose how much they paid to recover from the attacks.

Three districts have claimed statutory exemptions to withhold all or nearly all their records, and the rest aside from Fairfax have provided nothing more than an acknowledgment of the Daily Dot’s request.

More than 830 schools have been hit by ransomware this year, according to the cybersecurity firm Emsisoft, and the FBI warns that these attacks are on the rise. From the rural Deep South to the suburbs of Los Angeles, hackers are hitting school districts across the country indiscriminately.

In 2020, 84 incidents disrupted learning 1,681 individual schools, colleges and universities. Stolen info relating to kids and/or teachers was posted online in 22 cases.https://t.co/NmVd2dZv3F

— Brett Callow (@BrettCallow) July 28, 2021

But the numbers could be much higher because there’s no nationwide requirement that schools report ransomware attacks. Most states don’t have reporting requirements either, and the ones that do don’t enforce the mandates or won’t release the information, research by the cybersecurity firm Recorded Future shows.

“We don’t have a lot of transparency into these attacks, and I’m concerned about that because we can’t solve the problem without that transparency,” said Allan Liska, an intelligence analyst at Recorded Future, who led the research effort.

The only way out of this situation, Liska said, is to require schools to share the details of cybersecurity breaches so the public can see why the attacks were able to happen.

That information should already be accessible through Freedom of Information requests sent by journalists, but schools have been unwilling to put their problems on display, despite being legally obligated to do so.

“That’s a simple first action that I think everybody can agree on, that you should have to report a ransomware attack if you’re a school,” Liska said. “It’s taxpayer dollars—even if the insurance pays for it, it’s taxpayer dollars to pay for that insurance policy.”

Cyberattacks can force districts to cancel school for days at a time. They can put students and employees at risk of identity theft if hackers publish stolen data. And these criminal endeavors can carry seven-figure price tags that have to be paid for with public funds.

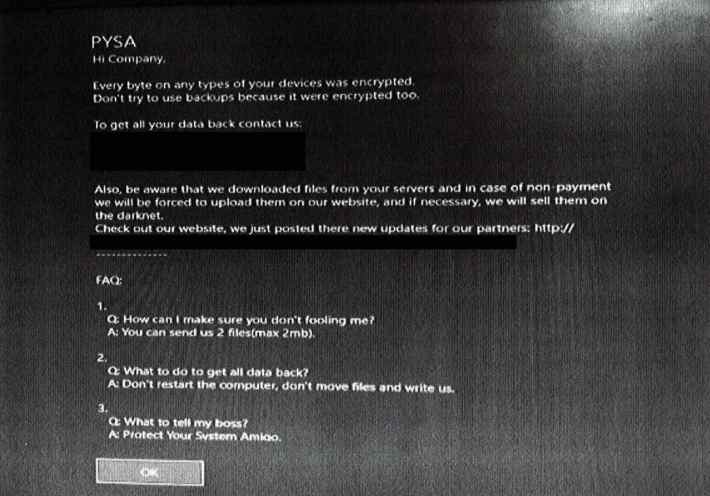

When hackers using PYSA ransomware attacked Haverhill Public Schools in Massachusetts earlier this year, they encrypted parts of the district’s computer system, disrupting email and phone service and forcing the district to cancel school.

The hackers then demanded a ransom to decrypt the data, threatening to leak sensitive information on the dark web if the district didn’t pay up.

“[B]e aware that we downloaded files from your servers and in case of non-payment we will be forced to upload them on our website, and if necessary, we will sell them on the darknet,” reads the ransom note, obtained by the Daily Dot.

The district brought students back to school the next day, but it hasn’t said whether it paid a ransom and it denied multiple requests to provide more information about the attack.

The only record the Daily Dot could obtain on the attack was a two-page police report from the Haverhill Police Department, which came with a screenshot of the ransom note attached.

For school districts that did provide information to the Daily Dot, the cost ranged from exactly $0 for the Vicksburg-Warren School District in Mississippi—it claimed they did not have any documentation of extra costs—to nearly $1.3 million for Baltimore County Public Schools.

For other schools, the public is woefully under-informed about a problem affecting students and teachers at big urban districts and small rural ones alike.

Districts can face six-figure costs for fixing computer systems, recovering data, and getting help from firms that specialize in negotiation with hackers—and that’s separate from any ransom they might pay.

Even districts with cybersecurity insurance might have to shell out tens of thousands of dollars out-of-pocket before reaching their deductible.

Although Clark County School District in Nevada disclosed that it paid up to its $100,000 insurance deductible for a ransomware attack last fall, it wouldn’t say where the money went, only that it did not pay a ransom.

The emails the Nevada district provided to the Daily Dot were heavily redacted, sometimes to the point of unintelligibility. This secrecy is only legal because Nevada public records law allows agencies to withhold virtually any record relating to cybersecurity breaches.

Several districts also claimed legal exemptions from public records law for attorney-client privilege—one district’s lawyer told the Daily Dot that any email the district’s attorneys were copied on would be confidential.

Some schools the Daily Dot reached out to have withheld all or nearly all their records, claiming that releasing them would threaten the security of their computer systems, even though the Daily Dot agreed to reduce the scope of the requests to only include top-line figures with sensitive information redacted.

Adam Marshall, a senior staff attorney at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, said it’s important for districts to be transparent about issues as serious as ransomware attacks.

“Government agencies should be welcoming public involvement and public scrutiny of this, and other matters of public concern, and they should be providing the information that makes robust and informed discussions possible,” Marshall said.

All 50 states have laws requiring government agencies, including public schools, to make their records public upon request. These laws are a vital way for taxpayers to make sure their government is working for them, Marshall added.

“You can ask questions of public officials, but at the end of the day the proof is in the pudding,” he said. “It’s in the docs.”

Politicians on the national level are beginning to catch up to cybersecurity threats. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rep. Deborah Ross (D-N.C.) recently introduced a bill that would require victims of ransomware attacks to disclose ransom payments to the Department of Homeland Security.

But that law would not cover costly ransomware attacks in which government agencies refused to pay the ransom, and there’s no guarantee that the federal government would make its data public.

Meanwhile Liska, the cybersecurity analyst, is disappointed by the lack of action on the local level. Last year he went to a webinar hosted by three local Virginia lawmakers, where he asked them how they planned to protect governments and schools from ransomware attacks.

“I got blank stares,” Liska said. “Local politicians in particular need to be extremely worried about ransomware, and they don’t even know what it is.”

And if they do know, they aren't sharing.