Following revelations of the U.S. government’s widespread digital surveillance programs thanks to leaks by former National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden, a lot of people around the world suddenly decided they wanted better security on their email. Problem was, the technology out there was far too complicated for most people to use.

In fact, the complexity of implementing PGP, the most popular email encryption protocol, nearly stopped the Snowden leaks from coming out in the first place. When Snowden initially contacted journalist Glenn Greenwald, and said he would only pass along his information if Gleenwald installed PGP, Greenwald gave up because it was so hard.

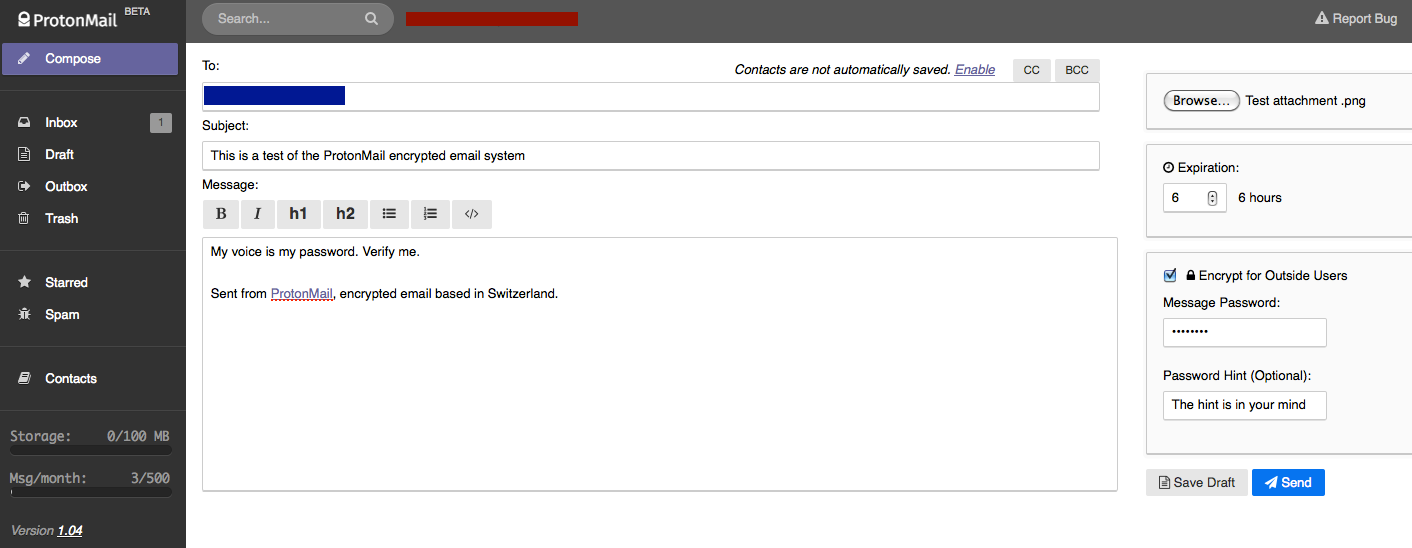

Earlier this year, a group of engineers at European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)—the same place that employed Tim Berners-Lee when he created the World Wide Web—decided to make sending private emails both secure and easy to use. Their solution: ProtonMail, a secure email system that’s fully encrypted end-to-end and just as easy to use as mass-market product like Gmail.

ProtonMail has proved so popular with the public that not only is there a long waiting list to sign up for new accounts, but a just-completed fundraising campaign on IndieGoGo was the most successful software product campaign in the crowdfunding site’s history.

The ProtonMail team set an initial goal of the month-long campaign at $100,000. That was shattered in three days. Two days later, they had doubled that amount. By end of July, ProtonMail had raised over half a million dollars.

“ProtonMail was created to give people around the world their privacy back. Raising money from the community was a very natural choice given our mission,” ProtonMail co-founder Andy Yen said in a statement.

In the middle of the campaign, the fundraising experienced a temporary setback that ultimately proved hugely beneficial. Shortly after the campaign launched, Paypal stopped processing donations to ProtonMail apparently due to concerns that creating an email system the government couldn’t gain access to was illegal.

As it turns out, it’s not illegal to make a email system intentionally beyod Uncle Sam’s grasp. After a public outcry, PayPal relented and reauthorized donations, saying the blockage was caused by a technical glitch.

The stoppage brought outsize attention to the project, and an influx of new donations flowed in, often in the form of Bitcoin form, which doesn’t require a third-party processor, such as PayPal, in order to digitally transfer assets from person to another.

ProtonMail has used the money from its fundraising drive to pay for redesigning much of its code, so the platform can support a larger number of users. There’s still a waiting list for people to sign up for new accounts, but Yen told the Daily Dot he hoped to have the queue cleared out within a month or two.

This significant reworking of the system’s guts is a primary reason why ProtonMail hasn’t opened up its source code to the public—something the company initially pledged to make a priority. Its failure to do so has drawn some pointed criticism because open-sourcing code for outside vetting is seen as way for developers to prove their creations are truly secure—or to publicly fix any problems that inevitably crop up.

?Our currently plan is to open source shortly after ProtonMail comes out of beta,” Yen said. ?There is also a large overhead that comes with maintaining an opensource project that we feel would slow down development at this stage.”

The company has also used the money to work on developing a mobile app. Yen noted that, at first, ProtonMail was skeptical about allowing an email service designed to be as secure as possible to be sold on app marketplaces, which could potentially expose it to the installation of secret backdoors without the developers’ knowledge.

?At the end of the day, we don’t really know a lot of what happens on these mobile devices,” he said. ?However, like it or not, mobile is now a big part of our everyday lives, and a mobile app is something a lot of our users have asked for. As a result, we have decided to build a mobile app.”

Yen added that ProtonMail will also make the app available outside of the app store environment when it is possible to do so.

Virtually all email services use some kind of encryption to prevent eavesdropping, but ProtonMail’s security is based around two additional security features. The first is that the company is based in Switzerland, a country that’s famous for giving extreme deference to corporate privacy rights. It’s rare for Swiss authorities to demand Internet companies turn over data about their users, Yen said, and that sort of thing only occurs a few times per year.

Even so, a recent court ruling against Microsoft, lent credence to the possibility that U.S. authorities can force companies to turn over data held on servers located overseas. Fortunately for users, however, ProtonMail is set up such that its management doesn’t have access to the private encryption keys required to turn the contents of users’ mailboxes from garbled gibberish into readable information. Even if a law enforcement or intelligence agency obtained a court order requiring ProtonMail to turn over information about one of its users’ data, the company likely wouldn’t be able to give officials anything worthwhile.

?Honestly, we are not surprised that a U.S. judge would rule in this fashion with regards to an U.S. company. Subpoenas can always be served anywhere in the world,” Yen said. ?What ProtonMail is doing differently is that we simply do not have the users data in unencrypted form. So while this ruling … is unfortunate for privacy rights in the states, it does not materially impact ProtonMail’s ability to protect user data.”

Photo Perspecsys Photos/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)