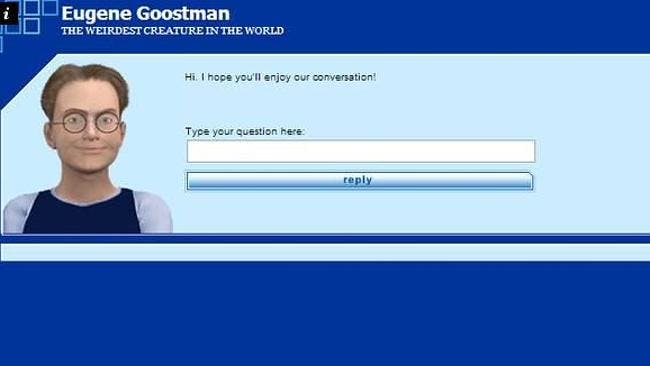

It’s happened: A computer has convinced us that it’s a human. At yesterday’s Turing Test competition, “Eugene Goostman” convinced judges that “he” was a 13 year-old-boy, when in reality Eugene is a computer program developed by a team of Russian developers.

The Turing Test was introduced by famed mathematician Alan Turing, when he asked, “Can machines think?” The experiment developed around this question judges whether a computer program can be mistaken for a human more than 30 percent of the time during a five-minute keyboard conversation. If so, it passes the test. Until now, it’s never happened.

But “Eugene” succeeded. However, the win comes with a small asterisk: Others claim to have passed the Turing Test.

In the University of Reading’s press release about “Eugene’s” win, these alleged victories were addressed:

Some will claim that the Test has already been passed. The words Turing Test have been applied to similar competitions around the world. However this event involved the most simultaneous comparison tests than ever before, was independently verified and, crucially, the conversations were unrestricted. A true Turing Test does not set the questions or topics prior to the conversations. We are therefore proud to declare that Alan Turing’s Test was passed for the first time on Saturday.

But what were these supposedly faulty wins? Well in 2011, a system called Cleverbot was reported to have passed the test. The software was presented at the Techniche festival and was reported to be 59.3 percent human, while the actual humans came in at 63.3 percent human. A quote attributed to “one of the humans at the event” remarked, “It was mesmerizing to watch a bot chatting just like a human, and people finding it so hard to determine.”

Cleverbot has a smartphone app if you want to try chatting with it.

One of the earlier claims of passing the test was developed back in 1989 by Dr. Mark Humphreys. Humphreys’ program was an “Eliza” chat bot, meaning it played the role of therapist to the chatting human’s patient. Traditionally, Eliza bots are sympathetic; Humphreys made his crude, aggressive, patronizing, and rude. The program evolved, eventually being named MGonz, and, and there have been many suggestions it passed the Turing Test, though nothing was ever made conclusive. In fact, in his conclusion, Humphreys entirely dismisses the importance of the Turing Test:

I have no problem with the concept of a machine being intelligent. Indeed, such already exist, for we are examples of such. Indeed, there is no evidence that there has ever existed an intelligence that is not a machine. And there is no reason why the principles behind how we work cannot be abstracted into an artificial system. My problem is with the Turing Test, not with AI.

In 2012, it was suggested that software designed for a bot tournament had passed the Turing Test. The UT^2 program competed against humans in a video game, convincing their opponents they were human as well. Of course, the traditional Turing Test wasn’t being administered here, though it was argued UT^2’s incredible ability to fool humans and appear human in its interactions give it such status.

Eugene’s win will likely only reignite debate over the purpose and conceit of the Turing Test, as well as how we measure the capability of AI technology. But clearly the winner here is famed technologist Ray Kurzweil, who totally won $20,000 on this bet.

H/T The Verge | Photo via Saad Faruque/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)