In the months since former National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden revealed how the spy agency snoops on the world’s data, millions around the world are suddenly worried about the security of their digital footprints. In an age where super-powerful, always-connected computer tag along in our pocket, is anything private anymore?

Luckily, there is an entire industry dedicated to ensuring every drop of your data is as secure as possible. And while many of the companies might be legitimately concerned about the little guy, the fact is the industry is booming—and it’s thanks largely to Snowden.

Take Abine, the makers of DoNotTrackMe, a popular browser add-on that blocks tracking programs secretly running in the background of many websites. On the Friday following the first wave of NSA revelations, Abine saw a nearly 100 percent increase in downloads over the week before.

“People were looking to take action and one of the easiest things they could do was install a tracker blocker,” explained Sarah Downey, an attorney and privacy analyst who has been with the Boston-based firm since 2010. “People just wanted to be able to do something to protect themselves.”

Downey noted that this growth has been sustained in the ensuing months. Recently the product surged in downloads, passing 10 million.

That success was endemic for companies throughout the industry. TunnelBear, which makes virtual private network (VPN) software that masks IP address so you can surf the web without being tracked, doubled its total number of users in the past six months. The majority of that growth came in the wake of the NSA revelations.

Then there’s DuckDuckGo.

Started by Gabriel Weinberg in 2008 as a reaction to what he saw as Google’s creeping infringement on personal privacy, the upstart search engine doesn’t track users or modify search results based on prior history. It both encrypts all of its information and, when possible, directs users to encrypted versions of sites rather than unencrypted ones.

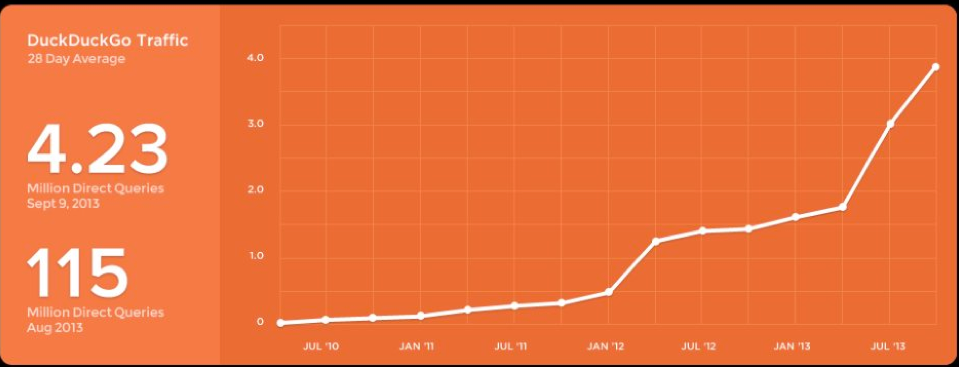

As the chart below shows, Snowden’s talking to the press may have been bad news for the NSA’s reputation, but it was very good news for DuckDuckGo:

Just before the NSA revelations, DuckDuckGo was doing just over 1.7 million search queries per day. By the end of that month, the search engine was approaching 2.7 million. By mid-September, the company was on the verge of cracking 4 million.

People aren’t just switching to more privacy-minded services. They’re also using technology different. TunnelBear co-founder Ryan Dochuk noted that, prior to Snowden, the vast majority of the people who used his company’s VPN software would only connect for a few hours, typically while they were using the unsecured WiFi at a cafe, and then log off.

“Now people are turning it on and leaving it,” he said. “People want to browse privately 24/7.”

As a result, the company is reconfiguring the way its product works. Most VPN software has to be configured specifically to work with each application that connects to the Internet. And there’s typically a lag of up to a minute while it connects.

TunelBear’s new program, which launched earlier this month, automatically starts the instant a computer turns on and runs silently in the background, essentially turning the the VPN’s anonymization into an automatic, unconscious process.

What’s really interesting here is that, even though the threat of government snooping is what’s driving a lot of Internet users to download online privacy products, many can’t actually prevent it.

“Even though we saw big spikes in installs after NSA revelations, we’re not NSA-proof,” Downey admits of Abine’s DoNotTrackMe program. “Pretty much no one is.”

Michael Angelo, tech advisor for the United States Department of Commerce, agrees. A veteran with more than 30 years of experience in the cyber-security industry, Angelo was recently inducted into the Information Systems Security Association Hall of Fame. And he says there’s no perfect online privacy system.

“Most people in the engineering world understand that if you’ve got the money of a government, it’s not a good story for privacy,” Angelo says. “Most people today don’t realize there really is no privacy anymore”—especially in a world where the digital detritus of our lives is increasingly scattered around corners of cyberspace that might not necessarily have the tightest security.

Even so, as Downey explains, “you can’t entirely go off the radar, but you can blur the picture a bit.”

Keeping as much user data encrypted as possible isn’t a perfect solution—after all, according to some reports, the government can unscramble much of the encryption currently in wide use. So one of the most effective ways privacy-minded companies have discovered to protect users is to not colelct data in the first. You can’t give the NSA what it wants if you never collect it.

“There’s only one way to truly protect the user: protect them from ourselves first and then from everyone else second,” said David Gorodyansky, the CEO of AnchorFree, a consumer VPN service similar to TunnelBear, and one of the 40 highest trafficked networks on web.

AnchorFree gets requests from the government for information about it users on a regular basis.

“Sometimes we get an info request and we’d really like to help because the people they’re looking for are really bad guys, but we honestly couldn’t because we just don’t collect that data,” Gorodansky explained.

Encrypted mobile voice and messaging system Seecrypt employs a similar strategy. If a law enforcement agency issues a subpoena on one of its users, at most the company can hand over confirmation that the user connected to its system. All the ancillary data, such as who the user called and how long the call lasted, would remain out of reach—”shredded” by the system as soon as the call is completed.

Even so, Seecrypt can’t avoid logging all user information—almost no company can. So Seecrypt moved its headquarters offshore. It calls the Cayman Islands home, while its servers reside in Sweden—a country Boulter calls “neutral” in terms of its willingness to fork over data hosted by private companies when foreign governments come calling. All those barriers turn filing a subpoena

All of this intentional obfuscation can’t help but raise a troubling question: Isn’t promoting products that could be easily used by criminals—the drug dealers, terrorists and child pornographers that tend to cluster in the darker corners of the web—the functional equivalent of aiding and abetting those criminals?

“Could we have criminals using the app? Yes, that’s a possibility,” Boulter countered.

“But there many things in everyday life that can be used for the wrong reason—a kitchen knife, for example. Our app is designed to be pro-privacy. It’s not designed for bad guys, but there’s little we can do to prevent bad guys from using it.”

Downey adds:

“We all need privacy for quality of life, but the people who need it the most are in the most dire straits—people in war-torn countries fighting against corrupt governments, activists who want to go to abortion rallies without everyone knowing about it.”

Privacy services are particularly hot right now, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the sector will be profitable forever. Taking a hands-off approach to collecting user data has closed off common revenue streams, such as targeted advertising and selling information to advertisers. That means these firms rely entirely on paying customers. They’re also competing with popular free products, like encrypted webmail service Scramble, and anonymization network Tor. When paranoia over the NSA dies down, paying for privacy may seem like a hard sell.

As for now, most industry experts predict a flood of new companies entering the online privacy game in short order, spurred by both a Snowden-inspired sense of moral outrage and the desire to make a whole lot of money.

Photo by Dev.Arka/Flickr