Pigeons might be considered rats with wings in many metropolitan areas, but it turns out those avian annoyances are actually quite adept at recognizing breast cancer in slides of tissue samples and x-rays.

These dirty birds can accurately determine whether or not a person might have breast cancer based on slides that show cancerous or healthy tissue, according to a study led by UC Davis researcher Richard Levenson and published in the journal PLOS One. After weeks of training, pigeons identified cancerous and benign images at the same rate as human radiologists.

Despite pigeons’ brains being the size of the tip of a finger, their brains’ neural pathways function the same way as those found in humans. These smart birds have been widely studied—pigeons have been able to identify between male and female human faces, the alphabet, and differentiate between styles of painting like Monet and Picasso.

Levenson, in partnership with researchers from Emory University and the University of Iowa, took pigeons through three different trials: histopathology, or identifying tissue cells through both color and non-colored images; detecting microcalcifications in x-rays, the small white spots that often signify breast cancer; and classifying cancerous masses in mammograms.

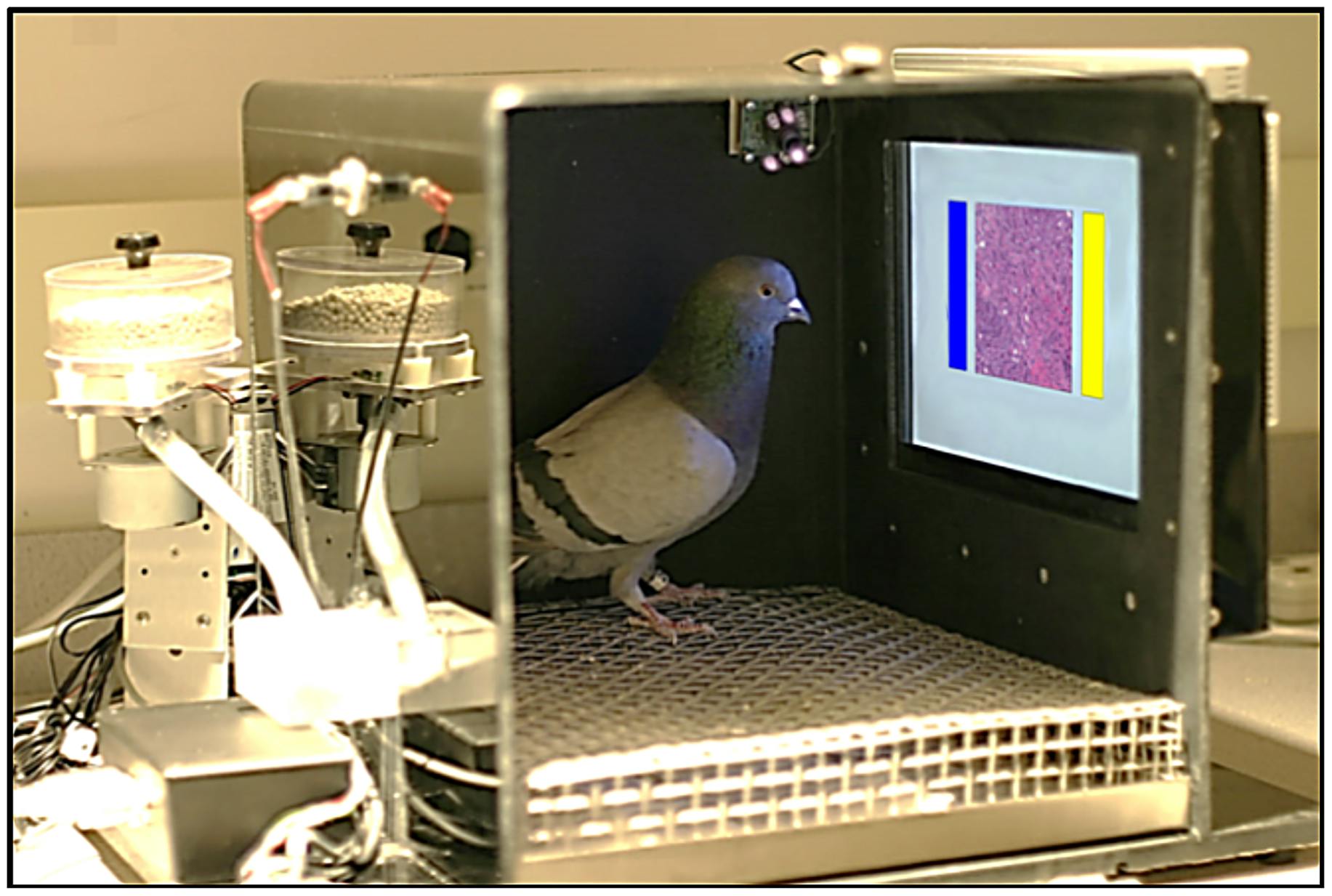

To train the birds, researchers put them in a tiny box with the images projected on a screen. Then the birds pecked at either a blue or yellow button that signified malignant or benign samples. When accurate, the pigeons were rewarded with food. This “operant conditioning,” not only showed that pigeons could memorize the different samples, but also taught them to identify new, unseen samples with 85 percent accuracy.

When researchers used “flock sourcing,” or averaging out the accuracy of groups of four pigeons, the correct response rose to 96 percent.

The birds were as accurate at recognizing cancer in the tissue slides, as well as microcalcifications, as humans. Masses in mammograms proved to be more difficult, like they are with humans, and the avian experimenters were only able to memorize the slides given, not recognize novel examples.

The pigeons proved to have an affinity for histopathology, as they achieved stable high performance as fast as or faster than with other visual discrimination problems studied in our Iowa laboratory.

Pigeons aren’t the first animals used in cancer diagnostics. Dogs have been shown to be able to detect prostate cancer by sniffing urine.

This study shows that pigeons could potentially replace humans when it comes to observing cancerous images and x-rays in perception studies, often considered mundane and expensive tasks. And pigeons could be used in studies that require many different parameters, observing more cases than what a human observer would ever tolerate, researchers said.

Pigeons could also play a role in developing technologies that could help human physicians and radiologists recognize and diagnose cancer. Flocks of pigeons certainly won’t be replacing cancer doctors, but their adept recognition could help improve humans’ development of diagnostic tools and software, including computer-assisted medical image recognition tools and vision research.

H/T Newscientist | Photo via Clickr_85/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)