Democracy only truly works if citizens participate. And that means we need to vote—something a surprisingly low percentage of Americans actually do. One way to boost voter turnout: online voting. But so far, no one has figured out how to make online voting safe from hackers, malware, and other vote-manipulation techniques.

Until, perhaps, now.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom claim to have created a system that alleviates the threat of malware on voters’ computers—the main problem keeping online voting from becoming a reality.

The technique, called Du Vote, would allow the voter to use an independent hardware device that would produce a unique code, which would then be entered into their computer to submit a verified ballot, thus mitigating the risk of vote manipulation.

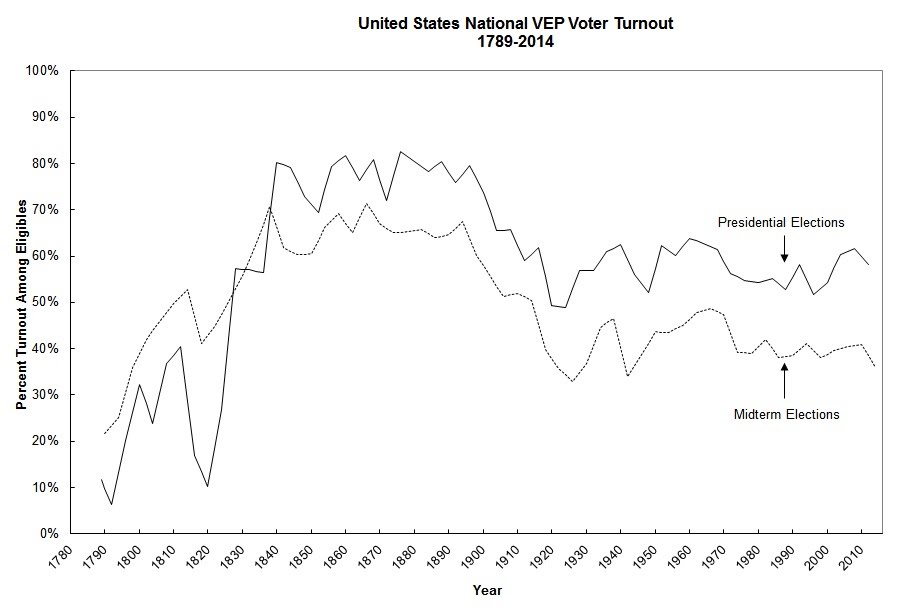

A viable online-voting system can’t come soon enough. The 2014 midterm elections saw the lowest voter turnout since 1942, according to the United States Elections Project, with just 35.9 percent of voting-eligible Americans making it out to the polls. In the 2008 presidential election, which enjoyed the highest turnout since 1968, only 61.6 percent of eligible Americans voted.

A variety of factors lead to low turnout rates in U.S. elections, but one obvious one stands out: The fact that Election Day lands on a Tuesday means anyone who can’t get off work or find someone to take care of the kids may simply not be able to make it. Add in some good ol’ apathy, and it’s easy to see how some 40 percent of voting-eligible Americans simply fail to cast a ballot. By making voting as easy as buying new socks on Amazon, the theory goes, far more citizens will exercise their democratic right.

Professor Mark Ryan, who led the research, likens Du Vote that of Internet banking in the U.K., where a similar sort of device is used to login.

“We’re going a little bit further because we’re not just doing it to authenticate the user,” says Ryan, “we’re doing it in order to help the user through the voting process, which will in a way deprive the untrusted platform of a knowledge of your vote and the ability to interfere with your vote.”

In other words, nobody would be able to mess with your vote because it would remain secure from any outside intrusion.

The small piece of hardware never connects to the computer so it cannot become infected. “It’s a completely standalone device, but it does have some data,” explains Ryan. “It’s got a unique key, which is unique to you the voter.” Through this, Du Vote’s creators claim, you avoid the threat of malware that may already be on your computer.

In addition, the Du Vote system also detects threats rather than simply attempting to prevent them. Malware could impact the vote after the number from the voting device has been entered into the computer, says Ryan, but it would be detected.

“The malware could change the code, but because it doesn’t have information about the key that’s embedded in the device, it wouldn’t be able to change the code into another valid code,” says Ryan. “The best it could do would be invalidate your vote, but if it does, you’re going to see that because the vote is going to be rejected by the server. It can’t undetectably change your vote.”

Still, Ryan concedes,no system is ever 100 percent secure.

Online voting has been tried—and tabled—in several jurisdictions. Estonia, which has perhaps the most famous online voting system, conducts online voting for hugely significant elections, such as its parliamentary vote, which has seen an uptick in online voting. The problem with Estonia’s system, says Ryan, is that they still can’t verify whether votes are real or manipulated.

“They don’t have [verifiable outcomes] in Estonia, and they don’t have that in any of the countries that have trialed any kind of electronic voting,” says Ryan. “This is really a major problem, because in Estonia, you’re vulnerable to whatever software they’ve chosen, the client side or at the server side.”

Norway has also tried to implement Internet voting systems, which officials say were all very secure. Last year, it decided not to proceed with Internet voting as it still “remained politically controversial”. Meanwhile the U.S.-based non-profit Overseas Vote Foundation, which includes a team of academics, is carrying out ongoing research to develop verifiable and secure online-voting techniques.

Verifiable outcomes, while also maintaining the privacy of the ballot, are vital, says Ryan, especially for voter confidence and dealing with voters or candidates who want to contest results.

The topic of remote Internet voting or electronic voting is renewed every so often when a large election takes place. The recent U.K. general election sparked the conversation again. In one April survey, six out of 10 voters said they believed smartphone voting would improve turnout. However, the growth of state-sponsored cyberattacks has once again highlighted the need for even greater security checks.

Ryan and his colleagues say they have a couple more years of research ahead of them before Du Vote could be deployed, but Ryan believes it may be ready for the 2025 U.K. general election. To do so, the system must move beyond academia and into the business world, where hardware manufacturers could help with deployment.

Ryan says his team has spoken with Northern Ireland company Opt2Vote, and they have identified a number of other potential collaborators, such as Scytl and Smartmatic.

The next step for the Du Vote team is more funding and more tests. The team is currently seeking funding from the British government to continue its research. This will be followed by trail tests, such as working with one constituency or even using the relatively small student elections at the University of Birmingham, to help fine-tune the system.

So, will you be casting a ballot over the Internet anytime soon? No, probably not. Online voting is coming—but we’ll just have make do with the old-fashioned system for a little bit longer.

Photo via Vox Efx/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)