When architects and historians Charles Matz and Jonathan Michael Dillon set out to scan a world heritage site in Harar, Ethiopia using lidar technology, they didn’t realize their 3D renderings would produce stunning works of art.

The pair, along with their research team, used the 3D-scanning technology to capture the architecture in the historic city of Harar, the fourth holiest city in Islam, in an effort to digitally preserve the ruins of once-beautiful gates in the city.

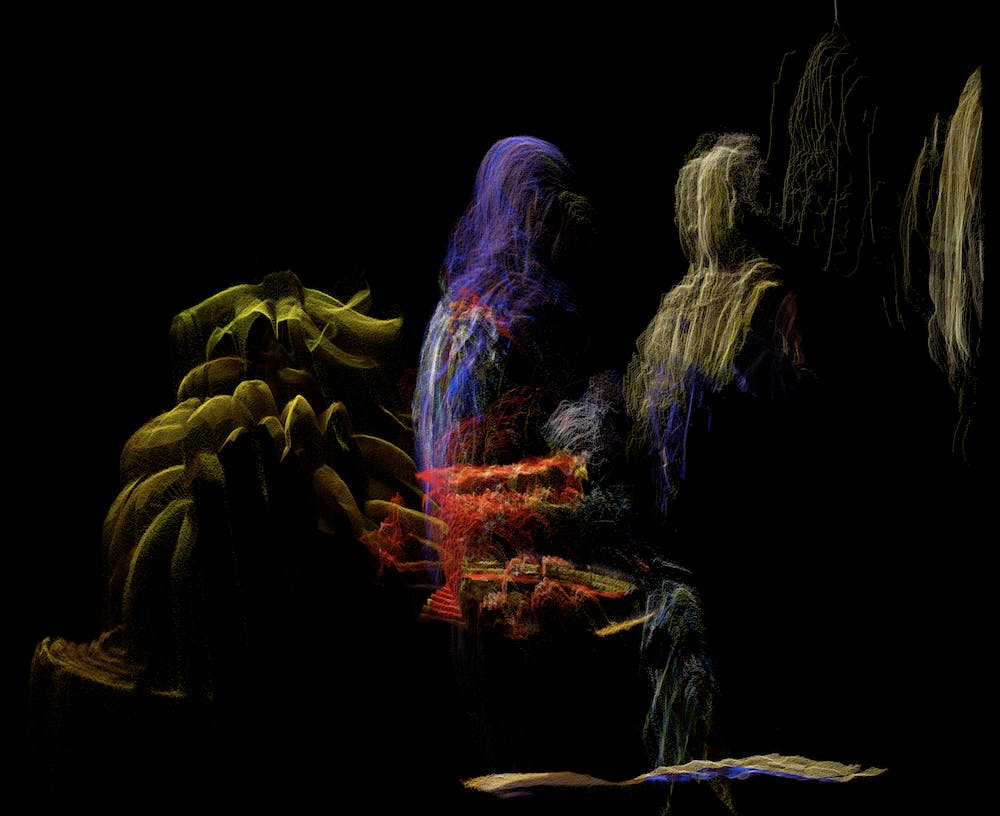

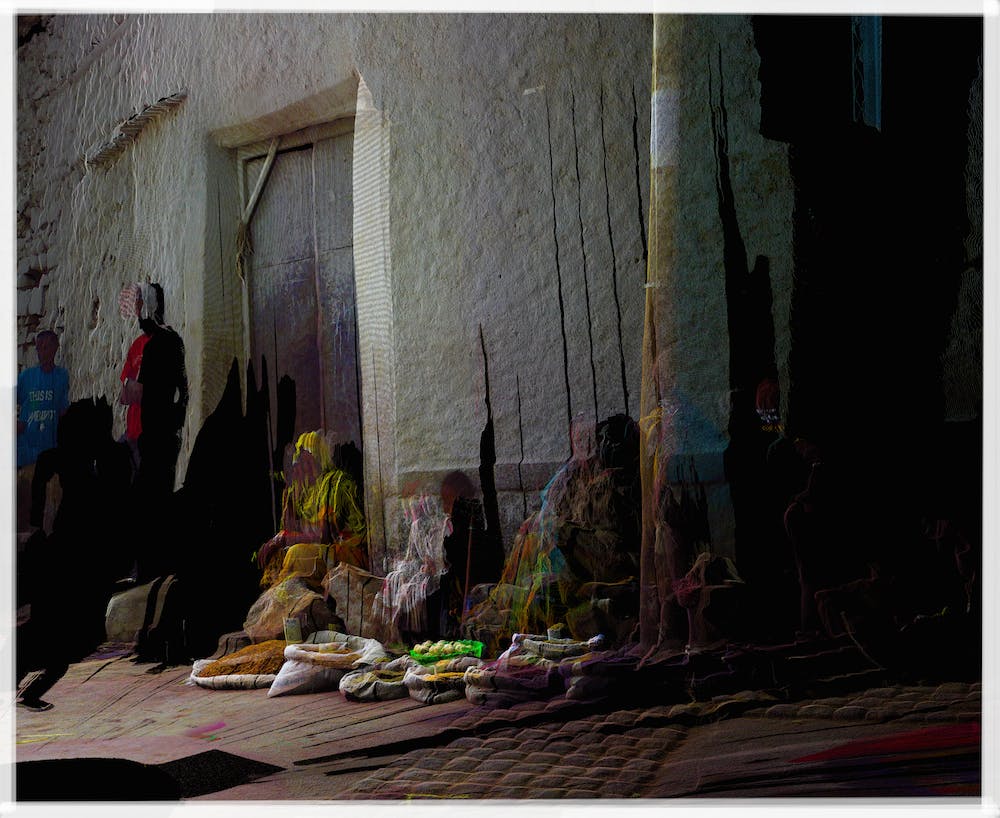

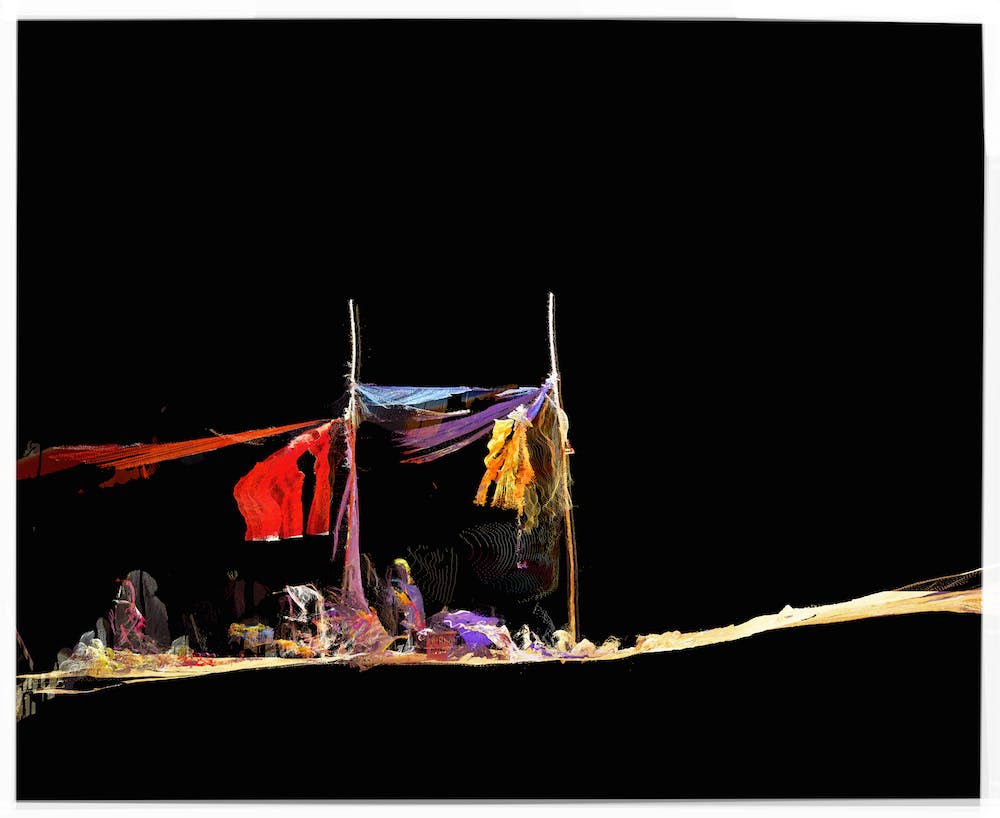

The team took numerous scans of locations throughout Harar, from markets to buildings to dusty streets, and in some photographs, ghost-like images of people appeared.

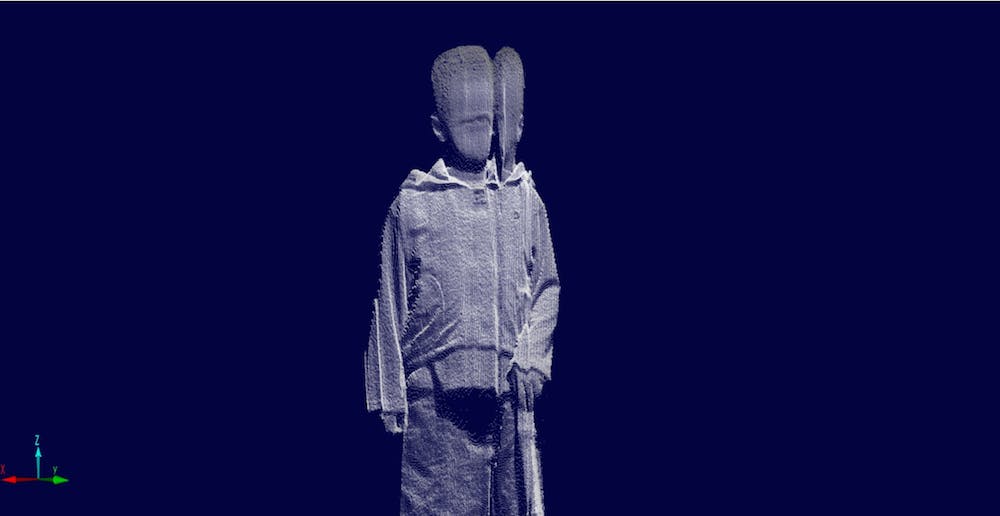

Lidar technology measures the three-dimensional structure of any surface by lighting up the particular area with a laser and measuring how light is reflected off the object. When capturing solid structures like gates and historic architecture, it provides researchers with a clear picture of the object. But it takes up to nine seconds to analyze the object, so any movement can throw off the image.

That movement is what caused Matz and his team to create stunning imagery of people in Harar.

Lidar technology is regularly used to map forests, architecture, and the coast. But the images of people in the city of Harar are almost otherworldly, and give some insight into the density of people the community, while creating an entirely new form of fine art.

Matz and Dillon are both involved in the art world, and the pair recognized immediately that the scans of the historic buildings weren’t just important for research purposes.

“There’s a strong tie-in to the early advances in two-dimensional photography or print photography and what is now digital photography,” Matz, an associate professor at the New York Institute of Technology’s school of Architecture and Design, said in an interview with the Daily Dot. “The potential future of three-dimensional representation of things in the art world—that is a subtext that’s extremely strong. We’re just coming to the beginning of discussions in the art world and our peers about what this could actually mean.”

The scans were taken in 2011 and 2012, and it took a year and a half to analyze all the data and then another year to plan how to reveal the research turned works of art. A team of three spent the summer of 2014 creating trial prints, figuring out the best works to display as pieces that could span multiple feet when hung in a show. The pieces were shown at the New York Institute of Technology’s “TRACES” exhibit.

The team originally planned to open-source the data collected from Harar, Matz said, but the images both surprised and excited the pair, and they decided to turn the data into art.

“The accident of having scanned the people was not something we had predicted,” Matz said. “And it was 10 times more interesting than the stuff that was sitting there, from the digital artist point of view.”

Lidar technology is already used in the fine art world for cataloguing, not creating, displayed works. In 2014, the Science Museum in London closed an exhibit that was a favorite of many visitors since 1963. To preserve the collection and let others revisit it long after the pieces were packed away, the museum used lidar technology to scan the entire exhibit to create a 3D rendering that people could visit virtually.

Hollywood puts lidar to use to create its own version of art. By taking 3D scans of locations where a particular film is set, filmmakers can create virtual versions of an area, removing the need to film on-site. Creators of 2014’s historical drama Pompeii took lidar scans of the famous ruins of a city that was destroyed in a volcano centuries ago.

“Every six months the technology improves both in software packages and in hardware,” Matz said. “I think a lot of it is driven by the fact that many Hollywood flicks are digitally composited, and there’s a strong push to get this technology on its feet.”

Creating the images using a lidar scanner is almost a work of art itself, he said. Each photograph is uniquely curated, and decisions like the coloration, where you take the image from, and how you capture it, whether there’s a white or black background, varies. And it’s a long process between collecting the data and illustrating what comes out of it.

Because the technology is constantly evolving, more detailed images and data will not only produce pieces like Matz’s and Dillon’s, but contribute to advancements in entertainment, largely thanks to game developers and defense contractors.

“There’s an interesting parallel between rise of this technology in the world of gaming, defense, and so forth, which are very well-funded industries, and also the fact that no one has tapped into it in the fine art world,” Matz said. “I think it has huge potential.”

Matz and Dillon plan on producing and distributing more fine art created from the same technologies used by the U.S. Geological Survey to scan mountains and forests. And eventually, these works could lead to more people experimenting with the entirely new art form.

For now, we’re left with the evocative images taken in Ethiopia, and a look at how 3D technology could further an art form.

H/T Live Science | Photo via Charles Matz