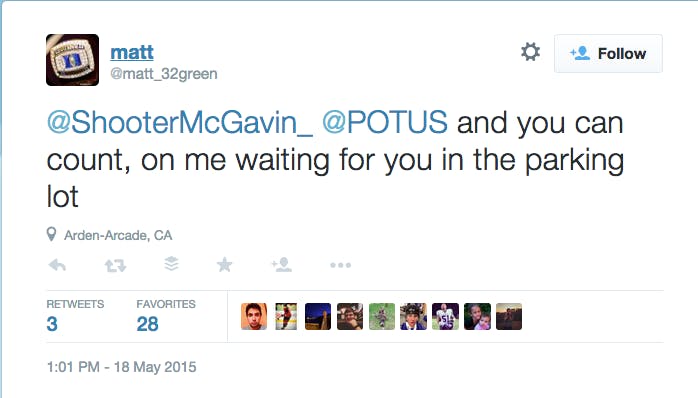

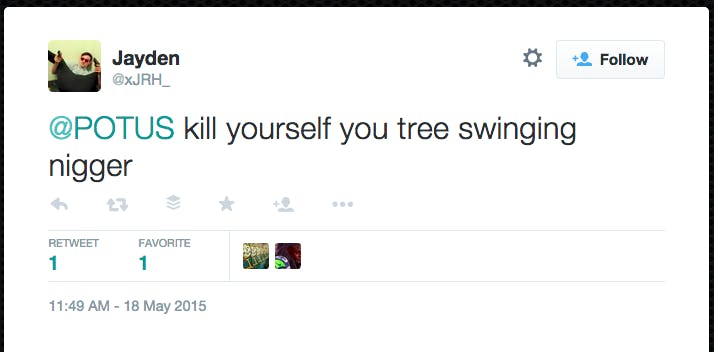

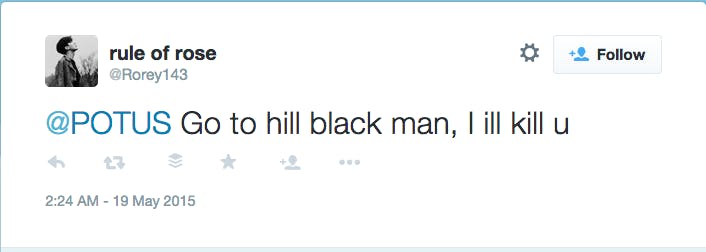

Almost immediately after President Obama created a personal Twitter account, @POTUS—his old one, @BarackObama, was mostly used by staffers—Twitter users began making threats.

We’re not anyone’s lawyer, but this can be a very bad idea.

Threatening the president of the United States is a specific crime, carrying a maximum penalty of five years in prison and $250,000 in fines. The Secret Service even has a dedicated team called the Internet Threat Desk. A spokesperson told the Daily Dot that the agency constantly monitors social media for potential threats but declined to share any specifics. And yes, there’s an illustrious history of Americans ending up in prison for tweeted threats toward the president.

In 2013, North Carolina man Donte Jamar Sims was sentenced to six months in prison for tweets like “Ima Assassinate president Obama this evening!” When Alabaman Jarvis Britton tweeted “I think we could get the president with cyanide! #MakeItSlow” in 2012, he got off with just a visit from the Secret Service. But he posted similar tweets a few months later, and he ended up with a year-long prison sentence. Ohioan Daniel Temple is currently serving a 16-month term for tweets like “so I gotta kill barack obama first.”

A Texas woman named Teddy Bear Paradise was sentenced to almost two years for mailing Obama a letter promising to kill him.

There’s little evidence yet on what happens when users tweet threats directly to Obama. But there’s plenty of precedent of people ending up behind bars for contacting the White House directly with threats in other mediums. A Texas woman named Teddy Bear Paradise was sentenced to almost two years for mailing Obama a letter promising to kill him, for example, and New York’s Christine Wright-Darrisaw got almost three years for calling the White House and describing to a staffer in detail how she’d kill the President.

Twitter itself is notoriously bad at policing its own trolls. While it didn’t respond to request for comment for this story, representatives for the company have previously told the Daily Dot that the company relies entirely on fellow users to report harassment and threats on the site, and it doesn’t self-police. It does sometimes share user information with law enforcement, though. Through the company’s now-regular transparency report, we know that in the most recent available data alone—the second half of 2014—that Twitter received 1,622 requests for information on 3,299 accounts from U.S. law enforcement, and that 80 percent of those requests were at least somewhat successful.

Considering how everybody on the Internet knows that the mark of a good troll is that you can’t even tell if they’re for real, what constitutes threatening the president, as opposed to just exercising your constitutionally-protected free speech?

Legally speaking, that’s a grey area that will likely get a little more color in the next few weeks. “Basically, the First Amendment does not protect true threats: any statement that conveys an intent to do harm or physical injury,” Hanni Fakhoury, senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told the Daily Dot. “What makes this particularly complicated and interesting is the Supreme Court is considering a case of whether a person actually had to show the threat of harm with Elonis v. United States.”

In that case, which the Supreme Court will rule on by the end of June, Pennsylvania man and amateur rapper Anthony Elonis wrote numerous violent threats about his ex-wife on Facebook. Elonis has admitted that his Facebook posts constituted an objective threat—meaning the words, taken out of context, clearly indicate a desire to harm a specific person. But he and his lawyers say it’s not a subjective threat—that a reasonable person would assume he would act on it—which would be a requirement for proving a true threat.

Or you could avoid the whole mess, not be an asshole, and not tweet even veiled threats to Obama. “My advice would be don’t do it at all,” Fakhoury said.

Illustration by Max Fleishman