On June 6, the Guardian began publishing stories about how the U.S. National Security Agency intercepts as much as half of the world’s digital communications1, often between American citizens. That same day, Edward Snowden, the former intelligence contractor responsible for leaking details of the program, gave an interview to one of the paper’s journalists, Glenn Greenwald, in his hotel in Hong Kong, where he had fled to escape prosecution. The whistleblower had given up his high-paying job at the agency and the life he’d built with his girlfriend in Hawaii. Greenwald, like the rest of the world, wanted to know why he did it.

“When you’re in positions of privileged access like a systems administrator for the sort of intelligence community agencies,” Snowden told Greenwald, “you’re exposed to a lot more information on a broader scale than the average employee, and because of that you see things that may be disturbing but over the course of a normal person’s career you’d only see one or two of these instances.”

The whistleblower did not see himself as exposing the corrupt acts of any one NSA agent or program. Instead, Snowden was revealing that the once-small military outfit built for signals intelligence in the Korean War had since evolved into a domestic spying organization that today spends billions to fund thousands of agents inside a 60-building surveillance complex.2 The NSA exploits secret surveillance court warrants and encryption loopholes, and taps into fibre optic Internet cables in order to spy on millions of Americans. (And according to former NSA Senior Executive Thomas Drake, who blew the whistle on the agency in 2006, its internal goal for the past decade has been to “own the Internet.”)

To Snowden, the lesson was simple: Somewhere in its six-decade history, the agency had spun out of control. The question is, how did it all go wrong?

NSA cryptographers during the Korean War (date unknown)

Before the NSA came to life on the eve of Dwight Eisenhower’s election, its job was done by a loose group of three independent intelligence outfits in the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The groups came into their own during World War II, as Washington began to see that significant signals intelligence, or SIGINT, could be invaluable in wartime3: On the Western front, British cryptographer Alan Turing’s Enigma machine had been able to decode German movements during the Allied forces invasion of Normandy. On the Pacific front, U.S. intelligence became so crucial that Admiral Chester Nimitz said SIGINT deserved credit for the Allied victory during the Battle of Midway.4

But just as the American SIGINT program’s successes came into focus during the war, so did its weaknesses. The three groups, two of which were run out of separate, converted women’s schools, often viewed one another as competitors. At one point, the Army and Navy went so far as to divide up intelligence work based on whether the day of the month was odd or even. (NSA historian Thomas Johnson would describe this peculiar practice as a “Solomonic Solution.”) The British government—in many ways superior in those days in terms of intelligence gathering—would later liken dealing with the American intelligence community to dealing with the colonies after the Revolutionary War.

The effects of this disorder were operational, as well. When, a few years later, the Soviets invaded Korea, the intelligence community was taken by surprise. The SIGINT agencies might have been able to predict the threat, as they had intercepted messages from Korea in 1949, but they had no Korean translators, dictionaries, or typewriters. And throughout the Korean War, the intelligence infrastructure continued to erode, so much so that in June of 1952 an Army general complained of how “during the between-wars interim we have lost, through neglect, disinterest and possibly jealousy, much of the effectiveness in intelligence work that we acquired so painfully in World War II.”

“The government badly wanted to centralize, to make themselves more efficient,” William Burr, a senior analyst at George Washington University’s National Security Archives, told me. They had tried, with little success, to consolidate the agencies on one previous occasion. In late 1952, to the objection of Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover, who didn’t consider SIGINT agents part of the intelligence community. Truman decided to try again. In the final months of his presidency he established the National Security Agency.5

At the time, the NSA reported to the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. In the Red Scare years of the 1950s, the CIA was by far the most dominant agency. “People focused a lot on human intelligence back in those days,” James Bamford, longtime U.S. intelligence journalist told me. “They had a lot of political power.”

But by the end of 1960, the U.S. was already a radically different country from the Korean War years: John F. Kennedy was the president-elect; four African American students who refused to vacate a Greensboro, N.C., diner after being denied service had sparked nonviolent civil rights protests across the nation; fears of a communist-wrought nuclear war increased as the U.S. injected its first few thousand troops in the escalating conflict in Vietnam; Harper Lee’s one and only book, To Kill A Mockingbird, won the Pulitzer Prize; and Elvis Presley had returned from a two-year tour of duty. Abroad, the world was settling into life after the Second World War: France had detonated its first atomic bomb; Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who had aligned his country with Cuba, was building a nuclear arsenal; and Israeli secret police had at long last captured Adolf Eichmann, one of the principal Nazi orchestrators of the Holocaust.

But by the end of 1960, the U.S. was already a radically different country from the Korean War years: John F. Kennedy was the president-elect; four African American students who refused to vacate a Greensboro, N.C., diner after being denied service had sparked nonviolent civil rights protests across the nation; fears of a communist-wrought nuclear war increased as the U.S. injected its first few thousand troops in the escalating conflict in Vietnam; Harper Lee’s one and only book, To Kill A Mockingbird, won the Pulitzer Prize; and Elvis Presley had returned from a two-year tour of duty. Abroad, the world was settling into life after the Second World War: France had detonated its first atomic bomb; Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who had aligned his country with Cuba, was building a nuclear arsenal; and Israeli secret police had at long last captured Adolf Eichmann, one of the principal Nazi orchestrators of the Holocaust.

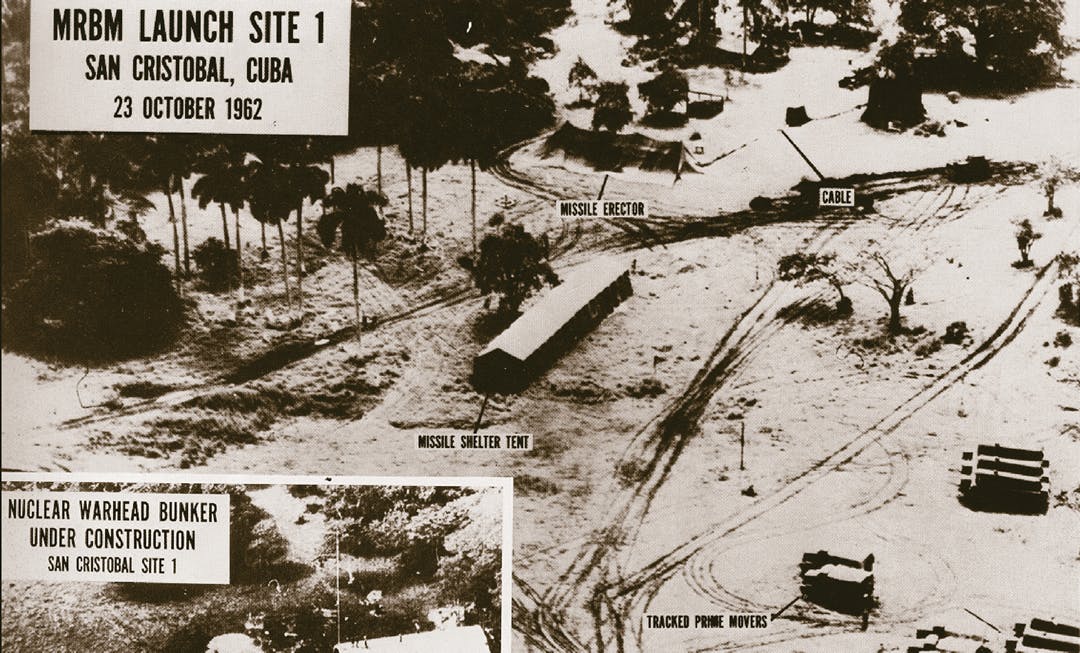

Against this backdrop, the balance of power in the U.S. intelligence community was shifting. A British spy working as a double agent for the Soviet Union had learned the name of a CIA mole in the KGB. In 1960, the mole was executed and the CIA’s line into the Soviet Union went silent. The NSA, on the other hand, was enjoying a period of unprecedented growth: Though it had little success breaking Soviet cyphers at the time, it had managed to use shipping logs and radio communications to follow the escalating U.S.S.R. arms buildup in Cuba in the fall of 1962. Tracking Soviet weapon shipments to down to the pallet, the agency was able to report that the Soviets had the ability to launch some 40 missiles at the U.S., putting 92 million Americans in harm’s way. As one intelligence evaluation concluded in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis, “NSA will continue an intensive program in the SIGINT field, which has during recent weeks added materially to all other intelligence.”

U.S. intelligence photo of a Soviet missile site in Cuba in 1962

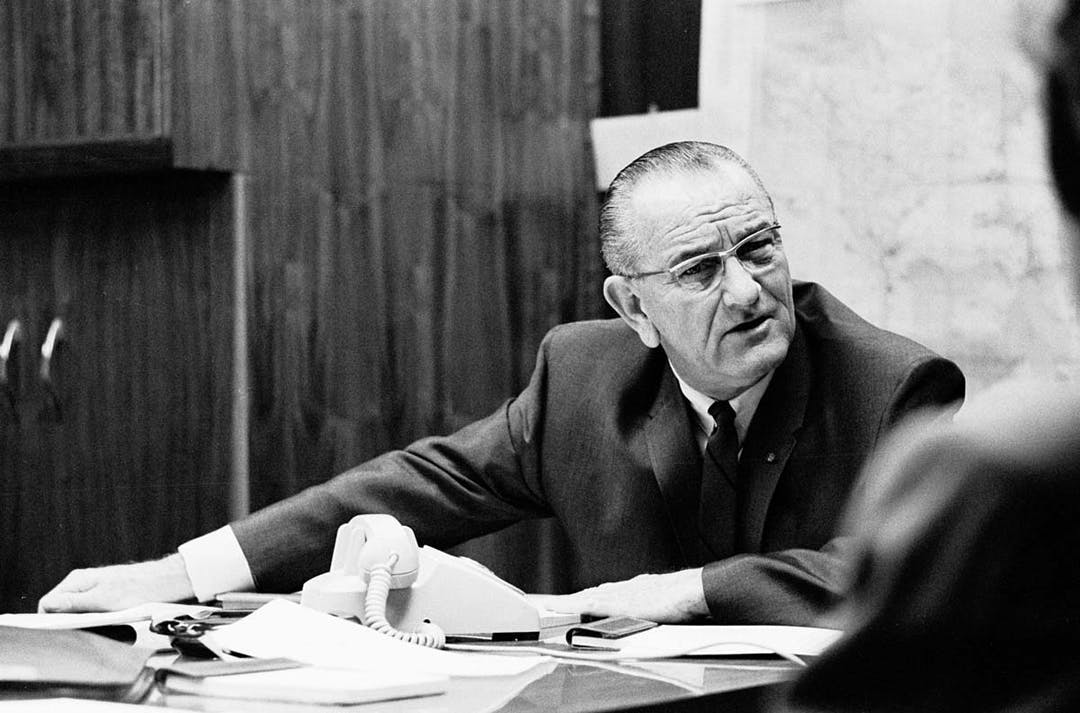

When President Lyndon Johnson took office following Kennedy’s assassination, he further shifted the the balance of power between the agencies. Johnson began pumping NSA intelligence directly into the White House, bypassing the CIA’s analysis of the information. “He was insecure on foreign policy,” Burr said, and wanted to know exactly what the agency was intercepting. “The Cold War instinct was taking hold.” Soon, Johnson would use that NSA intelligence as a pretext for war.

In 1964, Johnson received SIGINT intelligence that North Vietnamese forces had attempted to attack a U.S. ship in the Gulf of Tonkin. Based on this information, his secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, secured permission from Congress to enter the war in Vietnam (click here to listen to Johnson’s public address about entering Vietnam). In Bamford’s history of the NSA, Body of Secrets, an intelligence officer explained, “Everybody was demanding the SIGINT; they wanted it quick and they didn’t want anybody to take any time to analyze it. … It was just what Johnson was looking for.”

Years later, a declassified NSA memo revealed that the reports were not in fact accurate, and that no North Vietnamese forces had attacked the U.S. on the date in question. According to Bamford, McNamara had in fact been informed that the initial NSA reports of aggression were simply “freak echoes.”6 Apparently, McNamara claimed he had confused the report with earlier, accurate NSA intelligence of a North Vietnamese attack in the gulf. In the next decade, more than 50,000 U.S. soldiers would be killed in Vietnam.

President Lyndon Johnson at a National Security Council meeting (date unknown). Click here to listen to Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara discuss how the U.S. escalated the Vietnam War with faulty NSA intelligence.

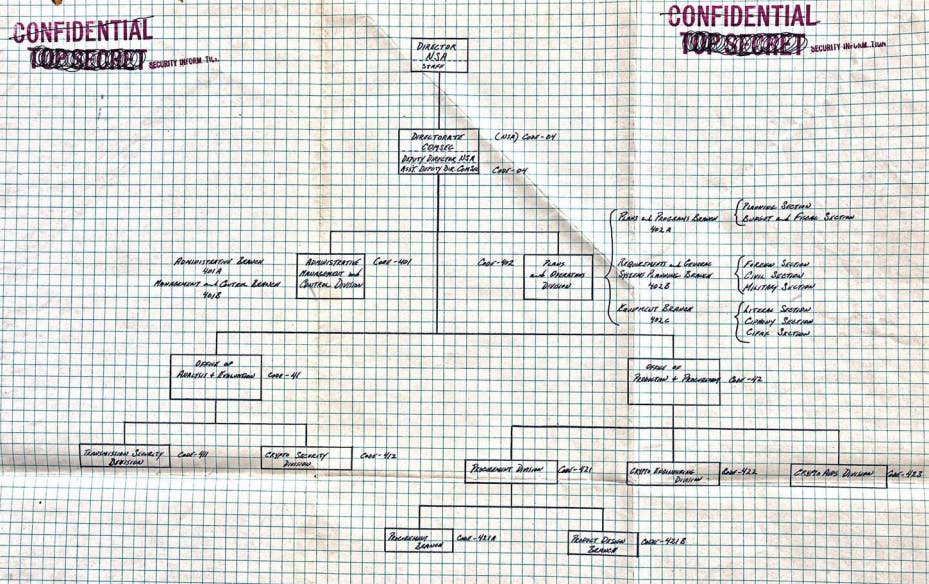

During these wartime years, the NSA grew from 33,000 to 72,000 employees, and was fast developing into the massive bureaucratic spy organization it is today. Organized much like the American corporations of the era, the agency employed a top-down structure that emphasized company loyalty and blind compliance with superiors. The more it grew, the more resilient this structure became.

Peter Ludlow, a philosopher at Northwestern University, pointed to the sociologist Robert Jackall’s 1988 book, Moral Mazes, for a description of the rules that govern such bureaucracies: “(1) You never go around your boss. (2) You tell your boss what he wants to hear, even when your boss claims that he wants dissenting views. (3) If your boss wants something dropped, you drop it. (4) You are sensitive to your boss’s wishes so that you anticipate what he wants; you don’t force him, in other words, to act as a boss. (5) Your job is not to report something that your boss does not want reported, but rather to cover it up. You do your job and you keep your mouth shut.”

“The NSA is nothing if not a 1950s-style bureaucracy,” Ludlow told me. “The consequence of that is you’re almost guaranteed to do evil.”

Intelligence gathering was then, as it is today, a messy business of spying, deception, and lies that, on a good day, results in information that strengthens our national security. It is, in fact, what we pay for. Evil, in this context, almost always refers to the notion of domestic surveillance, spying on the citizens who foot the bill. Theoretically, it is a line only toed in the most dire of wartime conditions; but by the early 1960s, the NSA, along with the rest of the U.S. intelligence community, had crossed it.

Early organizational chart shows the top-down structure of the NSA

History is context. And the most important piece of history for understanding how the U.S. intelligence community first began engaging in the outright illegal business of spying on American citizens is the detonation of the atomic bomb. Before Allied scientists unleashed the first nuclear weapon in the New Mexico desert in 1945, the notion that an entire country could be wiped off the map with what amounted to not much more than the push of a button was purely science fiction. As soon as it became reality, particularly after the Soviets detonated their own bomb only a few years later, the threat of communism became not so much an ideological fight as a battle for survival, however misguided it might have been. The events that would follow—the Hollywood blacklists, the McCarthy hearings, the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and the arming of Afghan fighters against the Soviets—must have seemed like the lesser of two evils at the time.

One operation, NORTHWOODS, which was never implemented, betrayed the mindset of the day. As Bamford, who unearthed the project in Body of Secrets, wrote, “the plan, which had written approval of the Chairman and every member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, called for innocent people to be shot on American streets; for boats carrying refugees fleeing Cuba to be sunk on the high seas; for a wave of violent terrorism to be launched in Washington, D.C., Miami, and elsewhere. People would be framed for bombings they did not commit; planes would be hijacked. Using phony evidence, all of it would be blamed on Castro, thus giving [the U.S.] the excuse, as well as the public and international backing, they needed to launch their war.”7 (Click here to read the declassified NORTHWOODS proposal).

If it seems impossible that rational men would conceive of such a project, consider one Senate Judiciary report of the day that warned of how radical right-wing anti-communist groups involved in “education and propaganda activities of military personnel” were becoming a powerful force in the U.S. military. “Running through all of them is a central theme that the primary, if not exclusive, danger to this country is internal Communist infiltration,” the report said. These groups were suspicious of Kennedy’s welfare and educational programs and believed the president to be a socialist sympathizer. Meanwhile, Kennedy had seized upon his own form of communist madness, authorizing the illegal wiretap surveillance of Martin Luther King, Jr. on the unsubstantiated belief that the Soviets were behind King’s activism.8

Multiple intelligence agencies got in on spying on the civil rights protestors. The CIA began a massive, recently declassified study of student protestors it dubbed “Restless Youth” that explored the communist connection to anti-war and civil rights movements. Despite finding none, the FBI listened in on King’s phone calls. Deputy director William Sullivan became so obsessed that he mailed King’s wife audio recordings of her husband’s illicit phone conversations with other women. The NSA, for its part, was engaged in a project called MINARET, which put King on a secret watchlist of 1,600 Americans. The list, as a recently declassified document revealed, also included Jane Fonda and Muhammad Ali.

Domestic spying had to some extent been going on in the NSA since World War II. The agency had been reading the telegrams of American citizens in bulk for years, under a project known as SHAMROCK. The MINARET watchlist, however, was created solely for domestic surveillance that the agency seemed aware from the outset was completely illegal. Memos from the operation, Burr told me, were distributed without attribution. “You could never really tell where it came from,” he said.

This spying continued until 1975, when the Church Committee, led by Idaho Senator Frank Church, began investigating the U.S. intelligence activities in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The committee found that the three major branches of the intelligence community, which it described as “those [agencies] whose powers are so great and whose practices were so extensive that they must be understood,” had conspired to capture telegrams, tap phones, open mail, and otherwise spy upon on American citizens for more than a decade.

Ultimately, the Church Committee would dismantle the illegal spying operations. They would force the three agencies to destroy all information illegally gathered on American citizens and help establish the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which was meant to draw a clear line between foreign and domestic spying activities by ensuring that the government had to obtain a court order if they wanted to surveil inside the U.S. The committee devastated U.S. intelligence activities. George H.W. Bush, who became the new CIA director in 1975, two years later admitted to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, “Henry, you are right. We are both ineffective and scared.”

In the aftermath, Kissinger conceded to President Gerald Ford that the intelligence community’s activities during this time were “clearly illegal,” raising “profound moral questions.” But the full implications of those questions wouldn’t come into focus until the summer of 2013. As a newly declassified document revealed, unbeknownst to Church, as his committee was questioning the NSA about project MINARET, he was one of the people being spied upon in the operation. Intelligence historian Matthew Aid summed it up to me with a line that was as true then as it is in the wake of Snowden’s disclosures: “Someone gave the NSA the names of two sitting senators. And the NSA went and did it!”

It’s hard to tell which is worse.

During the Church Committee’s investigation, committee staffer Loch Johnson, and Senator Walter Mondale, who would later serve as vice president under Jimmy Carter, asked FBI Deputy Director Sullivan how he could have carried out such audacious spying orders against the American people. According to Johnson, who is now a political scientist at the University of Georgia, Sullivan conceded the activities were, in retrospect, wrong, but he explained that he had no choice. He had two kids and a mortgage, he told Johnson.9

In recounting this story to me, Johnson sighed and said, “the banality of evil.”

NSA Director Lew Allen testifying before the Church Committee in 1975

Back in 1962, just as the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff was conceiving of operation NORTHWOODS, recently captured Nazi Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann was on trial in Israel for his role in organizing the Holocaust. Eichmann had orchestrated the mass murder of some 6 million people and was, without a doubt, among the worst war criminals in history. In attendance at Eichmann’s trial was the journalist and political theorist Hannah Arendt. Her account of the proceedings, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, would become one of the most influential works of 20th century political philosophy.

While observing Eichmann on trial, Arendt was shocked to find that, as she wrote, “everyone could see this man was not a monster.” Instead, he was something more of a mid-level bureaucrat: “Eichman remembered the turning points in his own career rather well, but that they did not necessarily coincide with the turning points in the story of Jewish extermination or, as a matter of fact, with the turning points in history.” In her opinion, Eichmann displayed an “utter ignorance of everything that was not directly, technically and bureaucratically, connected with his job.” As Ludlow put it, “Eichmann was a little bureaucrat who was involved in a bureaucracy engaged in unspeakable evil.”

While observing Eichmann on trial, Arendt was shocked to find that, as she wrote, “everyone could see this man was not a monster.” Instead, he was something more of a mid-level bureaucrat: “Eichman remembered the turning points in his own career rather well, but that they did not necessarily coincide with the turning points in the story of Jewish extermination or, as a matter of fact, with the turning points in history.” In her opinion, Eichmann displayed an “utter ignorance of everything that was not directly, technically and bureaucratically, connected with his job.” As Ludlow put it, “Eichmann was a little bureaucrat who was involved in a bureaucracy engaged in unspeakable evil.”

Arendt’s work, as it pertains to Eichmann, has always been controversial, as the word “banal” is somewhat absurd given the scope of his crimes. But it stands a broader exploration of how massive bureaucracies, particularly in the 20th century, can go awry without any particular desire to do so on the part of low and mid-level employees who are concerned only with their own career advancement.

Harvard psychologist Stanley Milgram, who was influenced by Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil, would build on her work by devising a test to explore how orders were received inside a bureaucracy. Milgram designed an experiment where scientists ordered test subjects to shock a third party every time that person answered a trivia question incorrectly. Some protested at first, but within the power structure set up by Milgram in the experiment, eventually almost everyone complied.

“People find themselves in systems and they don’t think of the consequences,” said Ludlow, “It’s a kind of self-deception.”

By the same token, the history of the NSA, for all it’s faults, is filled with well-meaning individuals. Bamford recounts several such stories in Body of Secrets: As one signals operator told him about his targets, “They’re humans too … and that humanness comes though. You learn these people as you work the job because it is the same people day in and day out and you learn their quirks and their tempers and everything about them. You know their ‘fist’ and the sound of their transmitter. You can tell if they’ve changed a tube in that transmitter after a while.” Another account, from an agent in the Vietnam War, gives much the same impression: “I recall very dramatically the fall of Dien Bien Phu. There were people with tears in their eyes. … We had become very closely attached to the people we were looking over the shoulders of—the French and the Viet Minh.”

How, then, can a massive organization of well-meaning people wander so aimlessly over the line into, as Kissinger put it, “clearly illegal” activities? “There are two kinds of moral lives,” said Ludlow. “One inside corporations,” and a second that asks “what are the consequences for the real world? There are rewards for being moral on the internal level. Less on the external.” Top-down corporations incentivize allegiance to the company. The NSA, for instance, has always been in competition for funding with the other intelligence branches of the U.S. For the past half century, it has been winning that battle. But to do so, it had to deliver more and more intelligence, be it of genuine national security interest or merely to satisfy the paranoia of presidents convinced the the Soviet Union is behind the American civil rights movement. And that means motivating employees to find ways to collect more information through raises and promotions. In other words, to incentivize spying.

As Snowden told Greenwald in his hotel room in Hong Kong, the individuals involved in carrying out the NSA’s domestic spying operations are part of such a large organization that they are often unaware of the broader implications of their actions. He facilitated NSA spying for years, thinking himself “just another guy who sits there day to day in the office.” Most employees have only minor concerns of everyday life: paychecks, insurance, college funds, taxes. For FBI Deputy Director Sullivan in 1975, it was two kids and a house payment. Unfortunately, inside the U.S. intelligence system, satisfying such concerns requires employees to move the agency further over the line of domestic spying.

It’s not that these organizations are inherently bad or evil, only that given the right conditions, there is little to stop them from going awry. In the 1960s, it was the Cold War that pushed the agencies over the edge, said Loch Johnson. “Now, the fear is generated by terrorism.”

In the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center, the NSA “now had its new enemy,” Drake told me, “after gazing at its collective navel as part of an existential identity crisis in the wake of the Fall of the Iron Curtain.”

In short order, the NSA began dismantling and circumventing the safeguards put in place by the Church investigation: They tapped directly into the fibre optic cables that carry the Internet; collected and analyzed the phone metadata of every American citizen; leveraged secret court warrants for Americans’ information on Facebook and Google; and sewed security loopholes into the encryption schemes that protect our most sensitive personal and financial transactions online.

“It’s time,” Mondale told me, “to take another look.”

Life inside the NSA is similar to many large American companies. Above: A 1958 newsletter advertising the agency’s Fall Festival.

Privacy has been treated as a sort of wartime ration. As President Barack Obama said in July 2013, “It’s important to recognize that you can’t have 100 percent security and also then have 100 percent privacy and zero inconvenience. We’re going to have to make some choices as a society.” And this may, in fact, be true—but we should be clear on exactly what choice we are making. The issue presented by Snowden’s leaks is not whether each individual program is acceptable; it’s whether American citizens any longer have control over the intelligence organization that was built to protect them.

“We thought after Church, those bad old days were gone,” said Aid. But, since September 11, 2001, the intelligence community has again seen an injection of money and personnel similar to the era of the Vietnam War. On top of that, as Mondale put it, “technology has changed the whole environment in which the agencies can operate.”

Concede for a moment that Obama is right, that nothing the agency has done is illegal, and that it is in our benefit to allow the NSA to spy on half the world’s communications in the short term. The question still remains as to whether, in the long run, there is any guarantee that the massive surveillance apparatus won’t spiral out of control as it did in during the Vietnam War.

Back in 1975, Johnson and Mondale raised this issue with Sullivan during the deputy director’s deposition: The practice of FBI spying had begun during World War II,10 as an authorized action in the name of national security. “That carried on, unfortunately, after the war,” Mondale observed.

“Senator, you are right.” Sullivan replied. “We could not seem to free ourselves either at the top or bottom, free ourselves from that psychology with which we had been imbued as young men, in particular, most all young men when we went into the bureau. Along came the Cold War. We pursued the same course in the Korean War, and the Cold War continued, then the Vietnam War. …We never freed ourselves from the psychology that we were indoctrinated with, right after Pearl Harbor, you see. It was just like a soldier in the battlefield. When he shot down an enemy, he did not ask himself: Is this legal, or lawful, is it ethical: It is what he was expected to do as a soldier. It became a part of our thinking, a part of our personality.”

If nothing else, Sullivan’s defense was honest. It’s not so easy to undo that which war begets.

…

End Notes:

1) The NSA to some extent disputes this claim. The agency taps into the fibre optic submarine cables that carry Internet traffic around the world, touching about 1.6 percent of all data moving across these lines. The “roughly half” estimate comes from analysis by the Guardian, based on the fact that much of the data moving along the Internet for media streaming would be of little interest to the agency. Only about 2.9 percent of Internet traffic is communications. Thus, 1.6 percent would be roughly half.

2) The exact size of the agency is unknown, but journalist James Bamford, in his 2001 book, Body of Secrets, tells the story of former agency Director William O. Studeman briefing Maryland community leaders on the NSA’s activities: “We’re the largest and most technical of all the [U.S. intelligence agencies],” Sullivan said. “We’re the largest in terms of people and the largest in terms of budget. …We have people not only here at the NSA but there are actually more people out in the field that we have operational control over—principally military—than exist here in Maryland…the people number in the tens of thousands and the budget to operate that system is measured in the billions of dollars annually.”

3) According to NSA historian Thomas Johnson, by the end of the war, an intellience report revealed that “cryptanalytic attack had been directed against the cryptographic systems of every government that uses them except only out two allies, the British and the Soviet Union.” (In retrospect, however, the British and the U.S. were already spying on the Soviet Union through an operation known as BOURBON.)

4) Five days after Hitler committed suicide, U.S. intelligence agents sent a secret memo to President Harry Truman already predicting that the Soviet Union “would become a menace more formidable to the United States than any yet known.”

5) To be sure, the early NSA initially suffered many of the same problems as its predecessors. As historian Thomas Johnson wrote in his history of the agency, a memo from 1953 recounted complaints that intelligence reports were “generally so cluttered with qualifying expressions as to virtually preclude their use by a consumer.

6) There is considerable debate over what actually happened behind the scenes of the Gulf of Tonkin resolution that escalated the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam conflict. According to Bamford, after the NSA misinterpreted the radar data and reported an attack, two ships in the Gulf reported “automatic weapons fire, torpedo attacks and hostile action.” Further complicating matters, North Vietnamese forces had attacked the U.S. two days earlier. McNamara asserted that he had conflated reports of these two events when testifying before Congress.

7) Kennedy ultimately killed project NORTHWOODS, though his exact reasoning is unclear as, according to Bamford, there is no known record of the discussion.

8) How exactly all of this came to be is revealed in a memo that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent to his field offices in 1963 insisting that the bureau “at once intensify our coverage of the communist influence on the Negro.” In the paranoid climate of the Cold War, it seemed lost on the short-sighted director that civil rights were in fact a meaningful enough cause for King’s moral outrage.

9) Mondale couldn’t specifically recall this interaction, which Johnson said occurred in a private room at the Logan airport.

10) Even then, the legality of such an operation was questionable, considering the recently passed Federal Communications Act of 1934, which ostensibly prohibited the wiretapping of U.S. citizens.

All photos via NSA