A 2014 study commissioned by UK marketing firm Tecmark found that smartphone users check their phones an average of 221 times a day. According to Pew Research Center, 67 percent of smartphone owners check their devices for new messages even when they don’t notice it ringing or vibrating.

With data like that—suggesting we check our phones about every six and a half minutes—it would not be difficult to make the case that we are addicted to our phones; at the very least, to the connectivity they provide.

So when Ben Broca says he’s found a way to keep people from sneaking peaks at the glowing screen in their pocket for an average of 288 minutes at a time, you get the feeling he might be on to something.

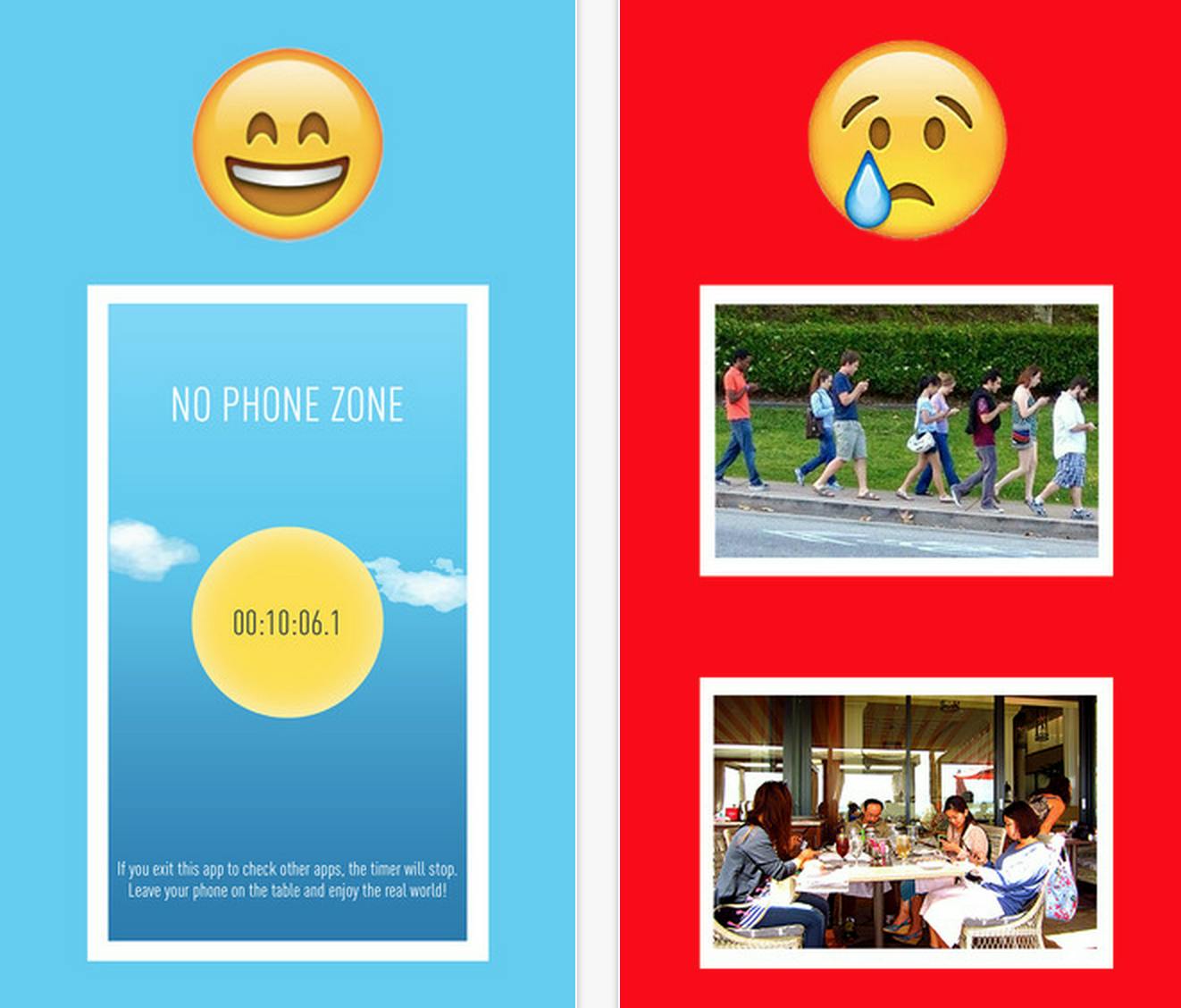

That “something” is NoPhoneZone, a new iOS app fresh out of beta that provides motivation to live in the now instead of inside a pixelated rectangle through a combination of social media and shame.

When you step into the NoPhoneZone—which you do by opening the app and starting a timer—an initial tweet is sent out to your followers, making them aware that you are in offline mode.

https://twitter.com/bencera_/status/602820965777559552

|OFFLINE NOW| boat 📵 #nophonezone http://t.co/5pY8fYxWnj

— Joe Alicata (@wirelessjoe) May 25, 2015

|OFFLINE NOW| Conserving my battery 📵 #nophonezone http://t.co/C65qOZtJlz

— Ryan Hoover (@rrhoover) May 23, 2015

The app doesn’t lock you out of your device or force you to wait a specific amount of time to feel the phantom vibes that make you check for texts that aren’t there—it simply counts. As soon as you do give in and return your your digital world, it sends out a second tweet telling everyone how long you lasted. If it’s a handful of seconds, it’s going to be pretty embarrassing.

“We’ve heard from multiple beta testers that because it tweets how long they are in the NoPhoneZone, they feel pressured to go longer periods without checking their phone— which is a positive thing!“ app creator Ben Broca told the Daily Dot.

Before designing an app made to keep people off their smartphones, Broca was busy trying to figure out how to get people to engage. “The inspiration for NoPhoneZone came after years of creating and developing social apps that were trying to get people to be on their phones as much as possible,” he explained.

“The nature of the job caused us to become exhausted by always be on our phones, and began to notice how much time our users, and most people spent on their phones — during dinners, on dates, at the gym, etc. It’s quite scary. We started thinking about a way to bring people’s attention on this issue by creating an ultra simple app that would help and motivate people disconnect more.”

Our screen obsession isn’t new; in the 1980s, a study by the New York State Psychiatric Institute suggested excessive time in front of the television led to academic failure in teens. But the iPhone is just 8 years old and smartphones have only become ubiquitous devices in our lives in recent years.

“It makes sense that only now people are becom[ing] more sensitive to the issue,” Broca said.

A low-tech pushback against screen gazing has started to gain steam in recent months: The similarly named NoPhone, a phone-shaped and -weighted hunk of plastic, launched on Kickstarter as a portable piece of brain trickery that sits in your pocket and gives the impression you have your phone with you; Light Phone strips away all means of communication that isn’t the traditional phone call.

Broca suggests that, even though we’re all guilty of the crime of checking our devices, the rage against the machine starts when we see that addiction in other people.

“Everyone at dinner experiences their friends check their phones compulsively, and no matter who you are, you will feel that it’s distracting and annoying,” he said. “I think people are experiencing this more and more often, causing people to resent these situations where notifications are more important than personal interactions, hence the ‘disconnect more’ trend.”

That’s the true crux of the theory behind NoPhoneZone. Broca believes people want to get away more often. The control group is the general population that checks its phone every moment the static starts to fade and they begin to see the real world. The experimental group are NoPhoneZone users.

“The aim of the app is to measure if most people will agree with us on the fact that this is an actual problem that will need to be solved,” Broca said.

But that’s not to say there isn’t some fun to be had while in the NoPhoneZone. As much as it exists for your own benefit as it tries to force you into living in the moment, there’s also a competitive element to it. Times are posted on Twitter so there’s always an element of knowing someone is watching, but the app goes a step further and allows you to directly compare with friends.

“There’s actually a leaderboard in the app which orders your friends by how long they’ve lasted in the NoPhoneZone and will show off on Twitter if when you beat one of your friend’s ‘score’,” Broca explained.

https://twitter.com/joshhyang/status/602245283628453889

Just beat @benbroca @maxstoller @bencera_ @elan_miller‘s high scores 📵 #nophonezone http://t.co/jbYHqEnRcB pic.twitter.com/SXVgnojUcD

— Sophia Dominguez (@sophiaedm) May 23, 2015

https://twitter.com/bencera_/status/602311117067722753

Top a friend’s best score and claim the crown for being the most present in your life. Or, if you really want to take it too seriously, spot when your friend sends out the initial tweet about firing up NoPhoneZone and start insistently trying to contact them with texts, Facebook posts, tweets, and anything else that will generate a notification. Does it defeat the purpose and completely go against the spirit of the app? Yes. But you’ll win.

The more result Broca would more likely want is for you to join that friend in entering the NoPhoneZone, then making the most of that time by hanging out with said friend. Do something you can’t do from behind a screen. Do something that won’t make you want to revert to your smartphone, even if it’s just for seven minutes instead of six and a half.

Photo by jase™/flickr (CC BY 2.0)