A New Mexico prosecutor is going to court in an attempt to force Facebook to turn over records of a group it banned after a shooting. The prosecutor says Facebook claims it deleted the records.

In June 2020, a self-styled militia called the New Mexico Civil Guard (NMCG) appointed itself guardians of a statue of a Spanish conquistador in Albuquerque. Shots rang out as protestors attempted to remove the statue. A man was wounded; another arrested.

Though the accused shooter purportedly wasn’t a member of the NMCG, Facebook banned it within days. The NMCG appeared on Facebook’s list of banned “dangerous individuals and organizations” the Intercept revealed last month.

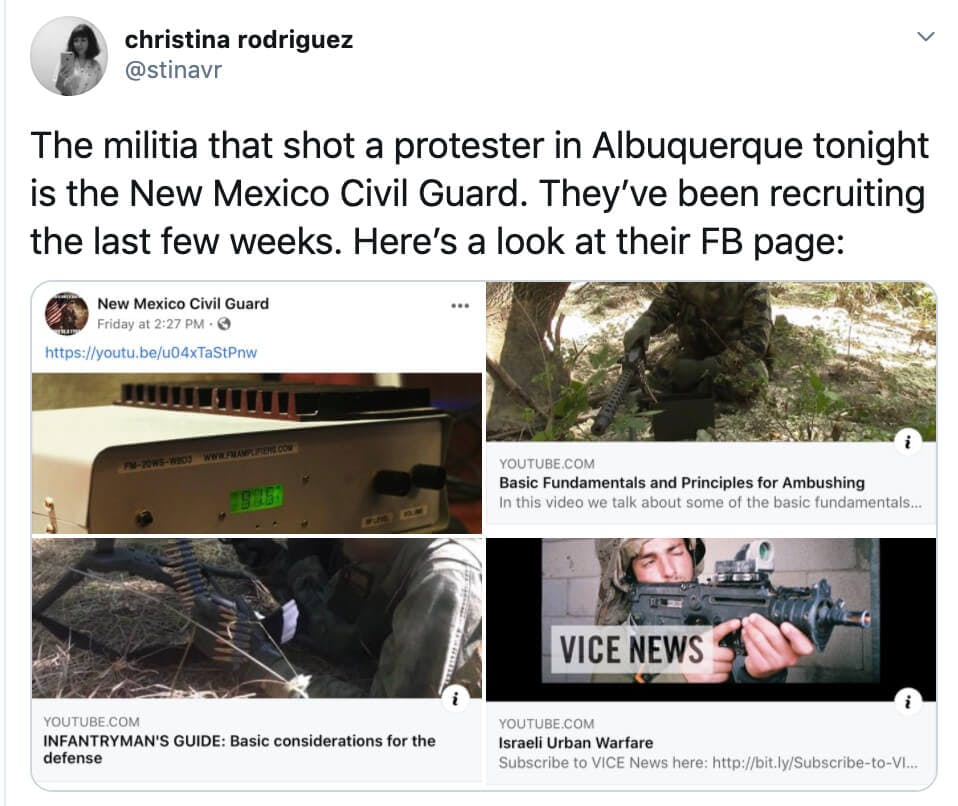

As the Daily Dot reported last year, the NMCG formed on Facebook a few months before the shooting. When civil rights protests rocked the nation, its members began showing up armed and in tactical gear.

Now the Bernalillo County District Attorney’s Office is suing the group for violating New Mexico law prohibiting acting as a police or paramilitary force. As such, it’s asking for Facebook’s internal communications about its decision-making process to ban the group and what it decided to retain about the account.

In a release, District Attorney Raúl Torrez said that Facebook has refused to turn over these records. He says Facebook claims the records no longer exist.

In a press conference on Monday, Torrez said they “find it hard to believe that a trillion-dollar tech company cannot retrieve account information about a group that the company removed from the platform because of its extremist activities.”

Torrez said it being unable or unwilling to provide information about extremists raises questions about Facebook’s ability to police itself.

“I think Facebook is going to be hard-pressed to make an argument that they’re actively engaged in policing extremist content,” he said.

Facebook says that it does have a process through which law enforcement can ask it to preserve records, the Washington Post reports, but that the agency must do so in a timely manner.

“We preserve account information in response to a request from law enforcement and will provide it, in accordance with applicable law and our terms, when we receive valid legal process,” Andy Stone, Facebook’s policy communications director, told the Post via email.

“When we preserve data, we do so for a period of time, which can be extended at the request of law enforcement.”

Facebook’s decisions and records in the documents leaked by whistleblower Frances Haugen indicate that it was well aware of groups like the New Mexico Civil Guard’s propensity to foment violence. A document in the Facebook papers called “Understanding the dangers of harmful topic communities” explicitly describes their risks of causing real-world harm.

The paper defines harmful communities as “those in which the topic or identity members converge around promotes or supports behavior or attitudes that cause, maintain, or risk harm to individuals within the community, in the wider Facebook community, or society at large.”

“A harmful topic or identity is one which […] includes a call to action that risks physical harm or societal violence.”

The Daily Dot’s reporting on NMCG last year shows that it meets these criteria. The group posted YouTube videos on killing and ambushing enemies, conspiracy theories, and repeated calls to “muster.” It also posted schedules for training exercises it apparently conducted.

The group claimed that it would need to step in if the police were defunded or disbanded and opined that it was likely the Albuquerque mayor would do so.

“If we’ve learned anything from 2020 it’s that it will be something new next month,” it wrote. “So join up and help us keep N.M. safe from threats foreign and domestic.”

Clearly, Facebook has long known of the possibility that people and groups who use its platform will take part in violent and/or unlawful activity. And it believes that leaders of groups like NMCG, whom District Attorney Torrez is trying to identify, are especially dangerous, according to the Facebook Papers. Yet it says that it deleted all the records of NMCG, even after banning it following a shooting at an event that it called on members to attend.

“My hope is that Facebook will take a step back, perhaps, and recognize that their ethical and legal obligations under the circumstances should lead them in new directions where they make these kinds of records accessible to law enforcement, accessible to state and local governments who are trying to hold the line against extremist activity in the state and across the country,” Torrez said.