Earlier this month, the New York Times reported on a new breed of art heist. Rather than stealing the famous bust of Queen Nefertiti from a museum in Germany, two renegade artists reportedly took a detailed 3D scan of the artifact and used the data to make physical copies. Then they delivered those near-perfect duplicates to Egypt—where they believe the original bust belongs—and put their scans online for anyone to use.

The story of “The Other Nefertiti” has a lot going for it: the intersection of art and new technology, the romance of two artists undertaking a mission to liberate a famous icon on behalf of its home country, and of course, the mystery of how they did it.

It’s that last little snag that has 3D printing experts wondering whether the whole thing is a hoax.

The artists behind the virtual heist, Nora al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles, told the Times they got their data by sneaking their scanner, a modified version of Microsoft’s Kinect gaming motion sensor, into the building underneath Badri’s scarf.

Once inside, she surreptitiously circled the Nefertiti, pulling back the scarf to expose the hidden scanning rig whenever the nearby guards were distracted.

Meanwhile, Nelles filmed her doing her work:

They’d reportedly been planning the October mission for 18 months.

Nelles and Badri claim they later handed off their data to unnamed hackers, who used it to create the detailed model that’s now online for anyone to 3D print.

But, according to multiple 3D scanning commentators, there are some major holes in the artists’ account of how they acquired their Nefertiti scan. For one thing, it’s way too detailed to have come from a Kinect.

Acclaimed 3D designer and printer Cosmo Wenman writes that “the Kinect scanner has fundamentally low resolution and accuracy, and that even under ideal conditions, it simply cannot acquire data as detailed as what the artists have made available. The artists’ account simply cannot be true.”

Others agree. Fred Kahl, a self-described “3D printing guru” also known as the Great Fredrini, wrote that he’s personally made over 10,000 Kinect scans, and none of them came close to the sub-millimeter level of detail in the Other Nefertiti.

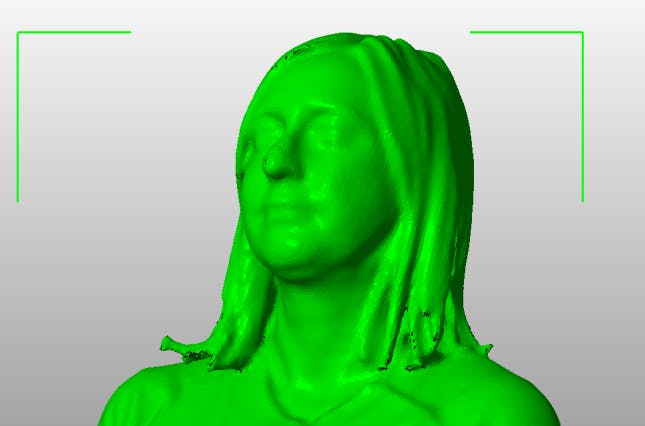

For reference, here’s a good-quality Kinect scan Kahl shared:

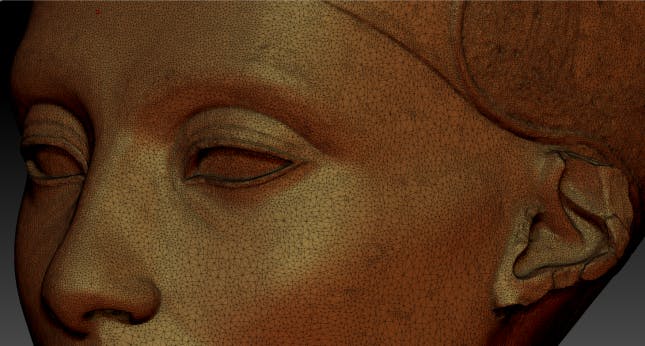

And here’s some detail from the Other Nefertiti scan. A Kinect image doesn’t even come close.

And that’s if the Kinect was even connected to a power supply and some kind of computer running scanning software, which appears doubtful based on the video Nelles shared. Is that Kinect even on?

If 3D printing experts don’t buy that Nelles and Badri pulled off their heist with a Kinect behind a scarf, then where did the Other Nefertiti come from?

There are three theories, all of them plausible.

First, Kahl and Paul Docherty (who works on 3D recreations of ancient Egyptian cities and art) have raised the possibility that the scan was stitched together from high-res photos, a process called photogrammetry. It wouldn’t be impossible to do—in fact, Docherty did it himself using photos from the Internet—but it would mean that the secret Kinect was just for show.

Second, and perhaps more likely, is a theory that the artists copied pre-existing data online. The Neues Museum, where the Nefertiti currently resides, does have its own high-res scan of the bust for preservation purposes. Could Nelles and Badri have hacked the museum and swiped it?

Unlikely, given the museum’s response to the stunt, months later. A spokeswoman told the Times “legal steps are not currently being undertaken as the scan seems to be of minor quality.”

But Wenman has another explanation that seems to fit perfectly: TrigonArt, the company that performed the scan for the museum back in 2008, has a 360-degree preview of its work online. And it’s a near-perfect match for the scans the “Nefertiti hackers” released.

“Even in this limited preview viewer, opening it up full screen and zooming in, you can see that every feature—including super-fine submillimeter details—appear to exactly match the model that the artists released,” Wenman writes.

He also provided a side-by-side image to bolster his case:

Thickening the plot even further, Nelles gave a video interview to All Things 3D just days before the Times story ran and admitted that the technical details—the scanner he supposedly used, along with the instructions for using it—were provided by the mystery “hackers” he later told the Times about.

He gave his source the results of the Kinect heist, and the source gave him back an implausibly detailed scan.

Wenman believes that source duped everyone involved, from the artists Badri and Nelles to freelance Times reporter Charly Wilder, who apparently never spoke to the unnamed person behind the final scan.

@CosmoWenman I had zero contact with the anonymous partners, presented what the artists told me, what museum told me, what experts told me.

— Charly Wilder (@charlywilder) March 7, 2016

Now the source is in the wind, having allegedly left Europe, and the entire truth of the matter may never come out.

Maybe the real art here isn’t the 3D model of Nefertiti, but the elaborate heist-movie scaffolding that’s propping it up.

Photo via TrigonArt