In 1958, a young University of Chicago professor published a paper that changed the way we view space and sparked a long-running desire to visit Earth’s star: the sun. Sixty years later, new advances in technology have enabled NASA to make the journey that could answer some of the most mysterious questions about our solar system.

Penned by Eugene Parker, “Dynamics of the interplanetary gas and magnetic fields” theorized that a high-speed magnetism was constantly escaping the sun. Parker called these puzzling forces “solar winds.” His theories about this powerful phenomenon have been proven countless times over the years through direct observation. But questions still remain.

In 1859, a massive coronal mass ejection (CME) breached Earth’s magnetic field, causing major disturbances. Dubbed the “Carrington Event” after the astronomer who recorded it, the flares were so strong they reportedly caused telegraph equipment to catch fire. At the time, the solar storm wasn’t much more than a fascinating episode to those who witnessed it. Today, given our reliance on technology, it would spark disaster—taking down the internet, lights, and everything we plug into a wall.

Nicola Fox, a scientist at NASA and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, described in a session at SXSW 2018 on Friday how NASA will reach the sun to investigate the dynamics behind these solars winds, specifically, what causes the material to get so energized. The space agency will also attempt to answer a physics anomaly that has left generations of scientists awake at night: Why is the sun’s corona nearly 300 times hotter than its surface?

“We’ve had to wait 60 years for tech to catch up to our dreams,” Fox, who called the trip “the coolest hottest mission under the sun,” said. “Scientists envisaged a mission we desperately wanted to do and it took awhile for the tech to catch up.”

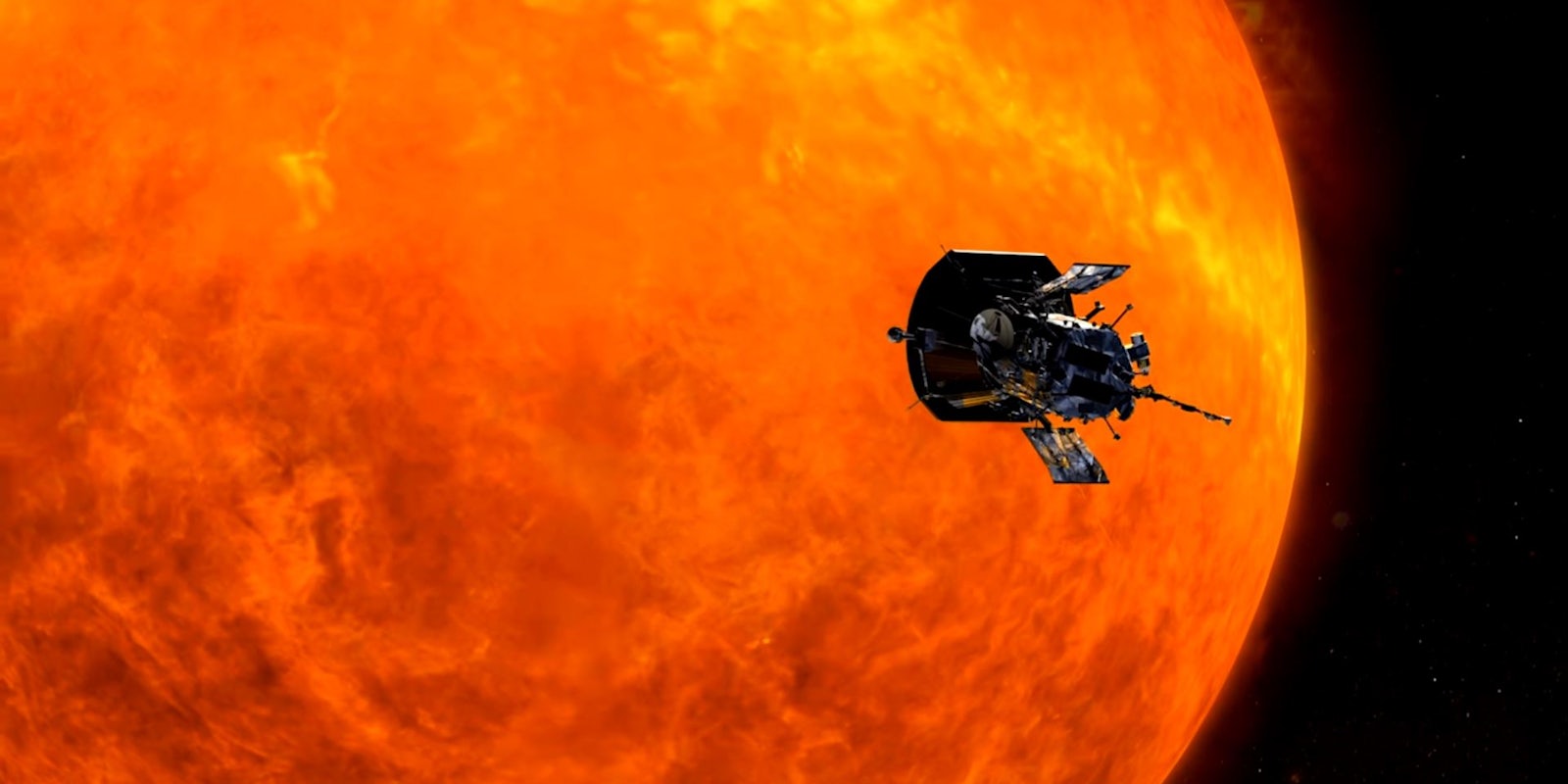

Later this year, NASA will have its first opportunity to answer some of these questions when the launch window opens for its latest spacecraft, the Parker Solar Probe. The probe will leave Earth on a six-year journey to the outer corona of the sun. There, it will take high-res images and measurements of the sun’s magnetic field, electrons, ions, and electric fields.

As you could imagine, launching a probe so close to the sun requires advanced technologies, none more important than the heat shield. Without the technology and techniques used to build this component, the Parker Solar Probe wouldn’t be possible.

Elizabeth Congdon, the lead engineer for the thermal protection system on the Parker Solar Probe, described the protective cone designed to shield NASA’s courageous spacecraft from the sun’s extreme temperatures. At 4.5 inches thick and with a diameter of 8 feet, the shield is relatively small when you consider its task. It’s also a lightweight, at just 160 pounds.

As the probe draws closer to the sun, the heat shield, or what Congdon calls an “8-foot frisbee,” will be exposed to temperatures as high as 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. If that sounds low it’s because, as Fox explained, the sun is like an oven—you can put your hand in it and be OK, but you wouldn’t want to touch its sides, or the 3-million degree particles surrounding the sun.

The shield’s carbon composite materials (a super-heated version of the stuff you find in tennis racquets or golf clubs), carbon foam interior, and honeycomb panels will keep the spacecraft bus behind it just hotter than room temperature. Condon explained that the materials aren’t necessarily high-tech, but “critical innovations” were required to piece it all together.

The Parker Solar Probe will be sent up from Cape Canaveral on a Delta IV Heavy rocket, the second largest behind SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. After being shot into space, the probe will use solar panels to power its way to Venus where it will borrow the planet’s gravity to kick off toward the sun. It will follow an elliptical orbit seven times between Venus and the sun, getting closer each time until it’s 3.9 million miles away.

That may not sound very close, but consider this: If you rescaled the Earth and sun to be one meter apart, the probe will be just four centimeters away from the sun. And because it will be getting closer and further from the sun, the probe will need to withstand alternating temperature extremes, from freezing to scorching back to freezing.

Another critical innovation enabling the flight is autonomous software. The Parker probe will supposedly be the most independent spacecraft ever to fly, correcting itself automatically if it ever heads in the wrong direction or if its solar panels become over-energized by the sun. These photovoltaic cells, which provide power for the craft, will be cooled by water.

The 20-day launch window for the Parker Solar Probe opens on July 31 when Venus is positioned correctly. The probe will take three months to reach Venus and another six weeks to the Sun’s corona. It will repeat its elliptical pattern six times for a total of 24 orbits.

Through the so-called “Hot Ticket” program, NASA will let you travel along with it. At least, in spirit. You can fill out an online form to have your name placed on a memory card that will travel aboard the probe, and become a tiny piece of spaceflight history.