“I just added footsteps,” said Ziv Schneider, a second-year grad student at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. She was showing me, using two of the three laptops required for the ambitious undertaking, a virtual museum gallery full of destroyed and missing art. “This one can run the Oculus development kit. It doesn’t work on the older computers; they get too hot.” With headphones on, I heard echoing, heavy impacts as we glided through the non-space.

“I think footsteps are really important,” she said. “There’s other stuff that people said, like, ‘I want to have other people in the museum’—or maybe you want an empty museum. It could be one of the options.” She added, “I managed to solve an issue with invisible walls today.”

These are some of many details that would never occur to a VR novice like me, each of utmost importance to the Museum of Stolen Art’s humble architect. We’ve already put aside the Oculus Rift goggles, since Schneider had lately encountered some bugginess with the related joystick: “The problem I was trying to solve earlier is the navigation; it’s a little off,” she said. Any movement is relayed as if through molasses. “I was working earlier on making it faster. … These controllers are really hard to calibrate.” Instead we viewed her environment through Unity, the game development software she taught herself specifically for this project.

“I managed to solve an issue with invisible walls today.”

“I used an existing model and redesigned it, which sometimes makes things harder,” she said of the sterile gray setting. “I designed it and changed it a lot, stripped down the things I didn’t need. One of my goals would be to redesign the space and have everything be a decision. I don’t know if I would put columns in.” All this effort goes well beyond the realm of homework: For a recent class, Schneider was assigned to propose a theoretical museum, then decided to press onward and make hers a reality. “Because I could,” she explained.

One wing contains missing paintings, many stolen in an infamous 1990 heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston—Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, Degas’ La Sortie de Pesage, and Vermeer’s The Concert, to name a few. Gauguin and Monet make appearances too. Another wing collects stolen photographs. “I just found it interesting, since photographs can be reproduced,” Schneider said, “but [the original] still has value. It’s a lot of Paul Strand, and Lewis Hine, classic American photography from the early 20th century.”

“In the Gulf War, I was wearing [a] gas mask that looked like this”—she gestured at the Oculus headset—“in the shelter.”

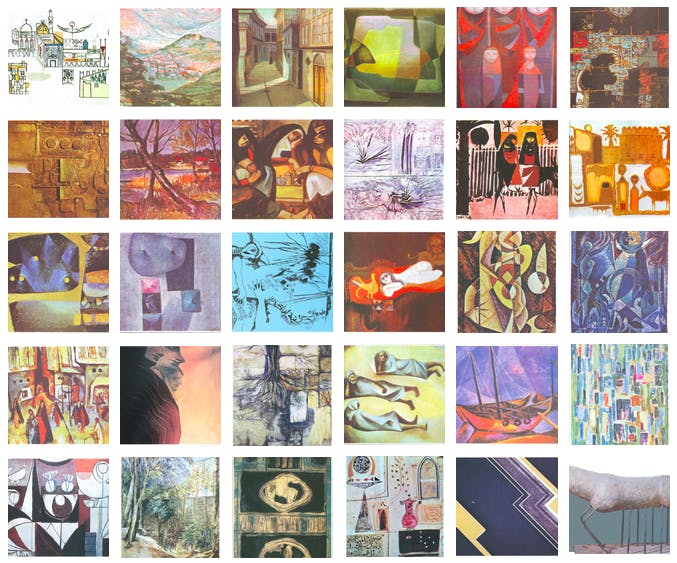

Two more sections of the museum are devoted to artworks and artifacts either looted or totaled during periods of unrest in Iraq and Afghanistan. “What happened in Iraq—it was political instability that led to it, and a lot of the items were looted by Iraqis during the invasion [of 2003] because circumstances allowed for it,” Schneider told me. “The condition of the archaeological items really deteriorated after Saddam Hussein lost power.” Things were different in Afghanistan: “A lot of it was looted by soldiers, and a lot of the items were returned. People were really surprised to see these pieces. They don’t relate them to Afghanistan. There’s a lot of intersection of cultures there, a lot of important historical pieces.”

While the appreciation of fine and otherwise inaccessible art is a nice aspect of the museum, Schneider wants the finished product to be a supplementary database affiliated with the branches of the FBI and Interpol that fight art crime. Her images are pulled from their Web archives of missing pieces, and through the headphones, a disembodied female voice instructs the user on what steps to take should they spot any in the non-virtual world. “If you see any of these works in real life, please report it to the International Police,” she says.

“It could be somewhere!” Schneider exclaimed. “It could be in someone’s basement, and you could identify it.” She cited the odd recent case of Hungarian art historian and researcher Gergely Barki, who, in watching the film Stuart Little with his daughter, noticed Sleeping Lady With Black Vase by Róbert Berény, an avant-garde painting that had disappeared in the 1920s, had been used as a piece of set dressing. “That stuff is out on the flea market, and Hollywood art directors buy it as decoration,” Schneider said. “They don’t know. I had a friend help me retrieve text about some of the pieces, and he found similar pieces on eBay that we reported to Interpol straight away. Sometimes if you dig enough, it’s not that hard.”

“There’s a lot of potential in the narration of data,” she continued. “We have archives, but they’re dry and boring and no one will look at them. VR kind of puts it in a new environment, for storytelling.”

That’s her angle for collaboration with a larger group invested in the recovery of stolen works and tracking down art thieves. “I’ve been contacted by some, but, you know, I’d love to work with Interpol. But they still haven’t replied,” she laughed. She was blown away by the organization’s archives, she said, and was equally inspired by the exhibition Last Seen, assembled by a favorite artist, Sophie Calle: “She addressed the paintings stolen from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and she had the security guards describe the pieces,” she told me. “Instead of the pieces, you had the way they remember them.” Schneider knew then that she could do something related in addressing “what’s left behind—the only representation that we have left, like a missing person poster.”

Still, there’s a lot of work to do and plenty of glitches to sort out. What Schneider showed me is really still a demo, and she wants to explore as many other fields as possible before she graduates later this year. Her background, in fact, is in graphic design. But VR will continue to be a focus for her as she heads into thesis country and beyond: “I like designing and creating content. My next project will be on Nova, because Oculus is not as available to everyone. … [VR] is new, and it’s exciting; it’s a new type of experience. People like new things. I think it’s a great platform to experiment in. It opens up a lot of possibilities for cinema, games, art.”

Pressed to reveal a preference for one pilfered artwork in particular, Schneider revealed a fondness for the Iraqi modernists. As someone who grew up in nearby Israel, the connections are tangible. “There’s a large percentage of Iraqi-descended Jews in Israel,” she said. “But also, you know, the Gulf War, when I was wearing [a] gas mask that looked like this”—she gestured at the Oculus headset—“in the shelter.” She was surprised at what plundering art theft databases revealed to her about the nation’s culture: “I didn’t know those painters—and digging up the information about them was really interesting, too.”

In the long term, Schneider said, she wants her museum to “work with a dynamic database that’ll update, so if a piece is retrieved, I can trade it for another one that needs retrieval.” I remarked that I could easily envision areas in real-world museums where visitors don VR goggles to get a look at what sort of masterpieces have been lost over the years, and that it was surely only a matter of time before Interpol picked up on her idea. “Yeah,” she said, not without a note of skepticism. “I hope they do that rather than sue me or arrest me.”

Photo via Jeffrey/Flickr (CC BY ND 2.0)