Members of the Indigenous community woke up on May 6 to find their Instagram posts for National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls had disappeared. After months of planning and events leading up to May 5, the day of recognition, activists, educators, families, community organizations, and more had shared infographics, resources, and stories to help get the word about the epidemic of missing and murdered Native women, girls, relatives and Two Spirit Peoples on Instagram.

Stories were posted with several hashtags including “MMIW” for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, “MMIR” for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives or Relations, and “MMIWG2S” for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People.

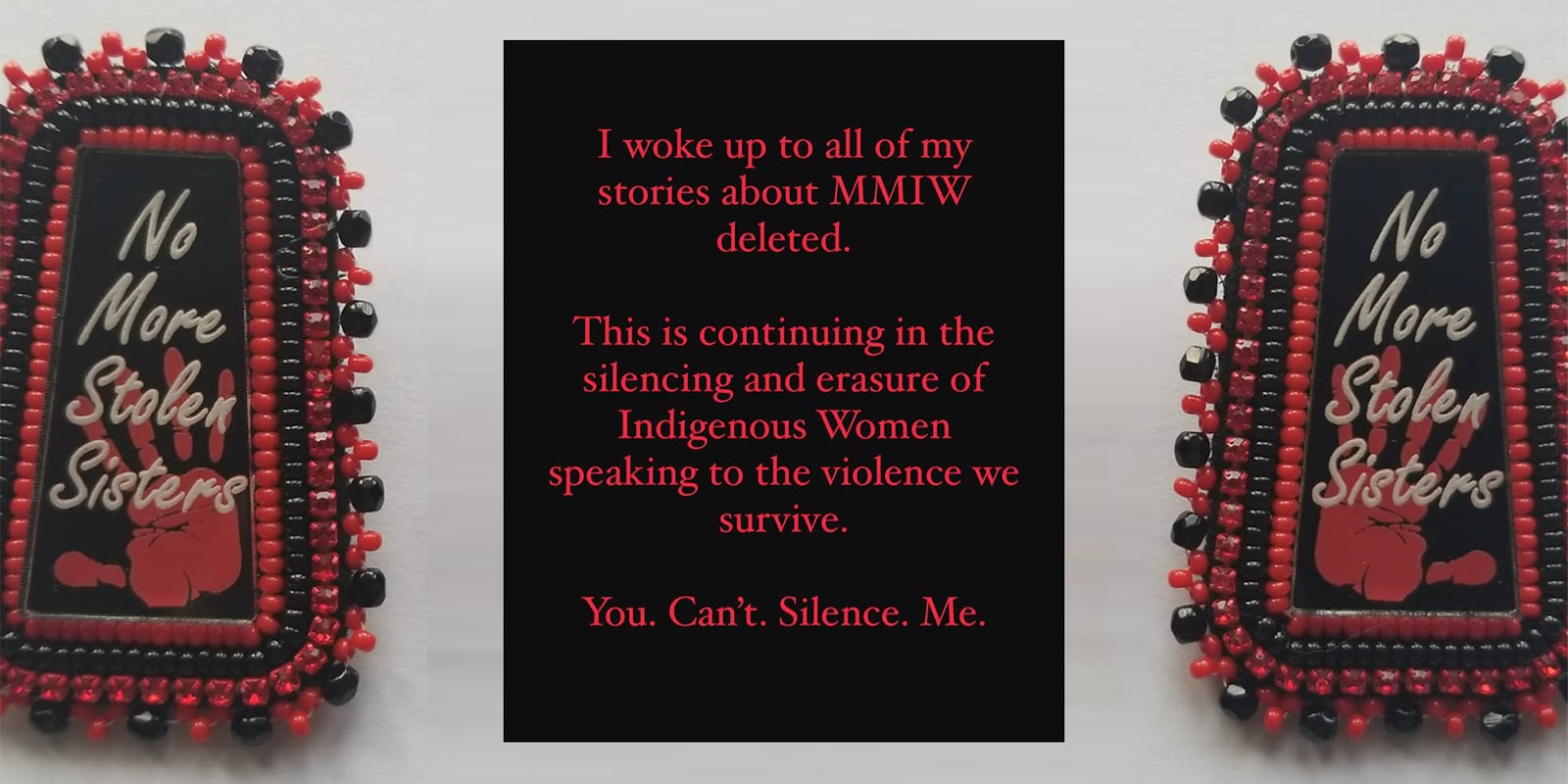

Corinne Rice Grey Cloud, Indigenous diversity equity and inclusions educator and Lakota and Mohawk woman, wrote on her Instagram: wrote on her Instagram: “I woke up to all my stories about MMIW deleted. This is continuing in the silencing and erasure of Indigenous Women speaking to the violence we survived. You. Can’t. Silence. Me.” Other educators and activists posted similar responses; many of the posts they had created and reshared were gone.

May 5 is “important because it amplifies awareness for our Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Trans, and Two Spirits,” Jolie Varela, a member of Nüümü and Yokuts Nations and founder of Indigenous Women Hike, said. “It is a day to mourn that loss but to also say that we have not forgotten, and that we are going to continue in this fight to bring justice to missing and murdered relatives and their families and to make sure that this doesn’t happen anymore.”

While the U.S. Senate only recently designated May 5 as National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls in 2018, Indigenous communities have been working to protect their family members and seek justice for their missing and murdered loved ones since the Canadian First Nation Communities began pushing for accountability for their loved ones in the 1970s lost on Highway 16 in British Columbia. The stretch of highway is known as the Highway of Tears, due to number of missing and murder Indigenous women who vanished and were found murdered on the road.

May 5 was chosen in honor of the birth date of Hanna Harris, a member of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe who went missing and was found murdered in 2013. The National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center (NIWRC) writes, “This long-standing crisis of MMIWG can be attributed to the historical and intergenerational trauma caused by colonization and its ongoing effects in Indigenous communities stretching back more than 500 years.”

The numbers are unimaginable. The Urban Indian Health Institute’s 2018 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls report found that of “5,712 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls reported in 2016, only 116 were logged in the Department of Justice’s database.”

And it’s not something just happening on reservations; it’s an urban and rural problem across all 50 states and beyond this country, explains Jordan Marie Daniel, founder and executive director of Rising Hearts and member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. There are many significant factors contributing to the epidemic including institutional racism within law enforcement and governing bodies, hyper-sexualization of Indigenous women, fossil fuel/mineral extraction and climate crisis, misclassification of people in databases (and much more). On top of it all, the crimes tend not to be reported in the media. The UIHI report found that “more than 95% of the cases in this study were never covered by national or international media.”

“Urban American Indian and Alaska Native communities … disappear not once, but three times,” the report says. “In life, in the media, and in the data.”

Indigenous communities maintain the fight for accountability year-round. While May 5 is an important day of awareness, which comes with a week of events, webinars, talks, fundraising walks and runs, the struggle for justice is present every day, a constantly ongoing battle for recognition of the plight.

So when Indigenous people found their May 5 stories about the day on Instagram were deleted, it “felt like the systems are letting [the families of missing and murdered loved ones] down again. They felt already let down because they haven’t had justice for their loved ones,” Daniel said, “Now their voices are being silenced from being able to be a voice for their loved one.”

Grieving families bravely shared their stories of their loved ones, opening old wounds of loss and hurt. Instagram deleted them, stories that also included resources, information, and actions to take to demand justice. Varela points out that it was devastating; all this emotional labor and tears to amplify this labor were gone.

Daniel also pointed out that May 6 should’ve been a day of decompression and healing but instead the entire community had to be on offensive, getting screenshots, checking in on one another and the families who shared so much.

Indigenous activists and organizations found out they were not the only ones affected. Colombian and Palestinian activists found their content erased by the platform as well.

Instagram responded on May 7 with a tweet trying to explain what happened. Instagram wrote, “On Wednesday (May 5), we began getting reports from people in Colombia that some of their content was not showing up in stories, and older posters were disappearing from Highlights and Archive…”

They determined that an update starting May 6 about reshared data was the problem and that it impacted all stories on May 5 until 3am PT on Thursday and highlights and archives that were reshared before Thursday.

“Unfortunately, the update resulted in our systems treating all reshared media posted before midnight as missing.” They go on to apologize to those in “Colombia, East Jerusalem, and Indigenous communities who felt this was an intentional suppression of their voices and stories.” According to Instagram’s statement, “tens of millions of stores were impacted.”

The head of Instagram, Adam Mosseri, also tweeted out an explanation and apology: “People around the world – from Colombia to East Jerusalem – use our platform to share what’s happening. We know it was a really bad experience. Ultimately I’m accountable for Instagram’s stability, so I own this. I’m very sorry.”

Many find the overall explanation insufficient and problematic. Daniel said she felt it was gaslighting and invalidating of their experiences. She notes this was not the first time activists have had issues with Instagram. Black Lives Matter activists found themselves blocked from posting anything with #blacklivesmatter last summer. Then, Instagram blamed an anti-spam tool.

Os Keyes, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington Department of Human Centered Design and Engineering, also doesn’t buy the apology. They point out that the Twitter apology is either wrong or a lie; after all, if the update started May 6, how could people start notifying Instagram on May 5? On top of that, Keyes explains that if Instagram was implementing a giant update, staff should have been monitoring it and should have seen that it was impacting millions of stories.

“The most generous interpretation possible to give here is that they are not thinking through the consequences of their actions, and that their testing infrastructure is held together with twine and hope,” Keyes says.

But it’s a larger problem with platforms like Instagram that are not transparent about content moderation. Adding to Daniel’s point, Keyes points out that this isn’t the first time Indigenous groups have had issues with the platform in the past year or so. In January 2021, VICE reported that a group of Indigenous beaders found their accounts banned or receiving repeated warnings from Instagram for no apparent reason.

It could point to a problem with the way that edge cases are handled. An edge case, Keyes explains, is the idea that something happens so rarely that it’s not factored into the design. So if only a small percentage of people are impacted by something, like an update, Instagram may still move forward.

“And it’s always the same people who end up [as] the edge cases. And when the same population are in the error rate every single time, that stops looking like an error rate, and that starts looking like active discrimination,” Keyes says.

Instagram also claimed the posts were restored, Varela and Daniel both point out that any stories that were past the 24-hour mark were not restored. “That information was missing,” Varela says, at a “really crucial time for people to be seeing these posts.”

But as Rice Grey Cloud explains, whether it was a technical glitch doesn’t matter. “The trust of the people has been shaken,” she says, “It still resulted in the pain of the families who were trying to speak on behalf of their loved ones.”

Both Daniel and Varela want Instagram to make amends, publicly acknowledging the harm to Indigenous communities and flagging organizations to donate to that were impacted by the platform’s censorship, like the Sovereign Bodies Institute, National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, Rising Hearts, and the Urban Indian Health Institute.

But it’s more so that Instagram needs to explain why Indigenous voices are the ones who wind up being censored.

This piece has been updated.