At their very core, what are sharing economy sites like Lyft and Airbnb really selling? On the surface, it may seem like the answer is amateur taxi rides and the opportunity to rifle through a stranger’s medicine cabinet. But the service being offered is actually something far more fundamental: information.

These companies may offer perks like free smoke detectors and bright pink car mustaches, but the real service being provided is a centralized channel through which to distribute information about people who have both the equipment and desire necessary to operate gypsy cab and hotel operations.

While both Lyft and Airbnb certainly have their detractors, MonkeyParking, a service created by an Italian app developer, presents a far thornier problem. Other sharing economy firms distribute, and then monetize, information about private property; MonkeyParking, on the other hands, does it for universally accessible, albeit scarce, slices of public space.

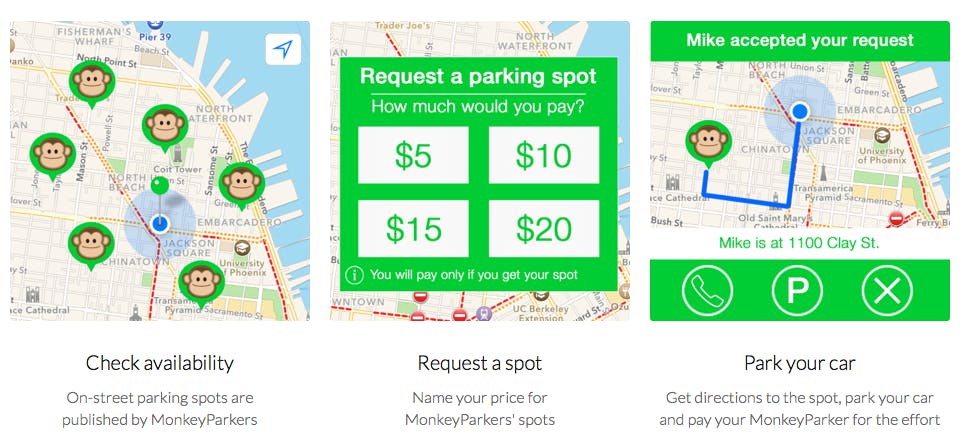

MonkeyParking allows drivers whose cars are currently sitting in parking spaces to sell the information about when they’re going to leave those space to the highest bidder. That highest bidder can then coordinate with the parker to swoop in on the space as soon as it opens up.

At present, the app only allows people to buy and sell parking spots in the city of San Francisco, which isn’t particularly surprising. While San Francisco has a tech-savvy reputation, meaning its denizens seem likely to actually use an app for parking, the city’s parking situation is also often unimaginably horrible. Attempting to find parking in certain areas of the city at certain times of the week regularly result in driving aimlessly for up to half an hour—for people who don’t want to shell out upwards of $40 a day for a spot in a parking garage.

Last year, permanent access to a single parking space in the trendy SoMa neighborhood sold for $82,000.

Just let that sink in for a second.

The reason for this scarcity is that San Francisco is densely populated and there typically aren’t enough parking spaces to go around. In recent years, city officials have attempted to alleviate this problem by instituting a ?smart” parking program where parking meter rates are adjusted up or down on a regular basis to find a price point that leaves at least one parking spot available at any given time on every block in the city—although the program has recently been scaled back.

Rates can vary anywhere between 25 cents and $6 an hour. The key is striking a balance that avoids pricing the less affluent out of the parking market entirely.

And yet, MonkeyParking’s very existence is evidence that San Francisco’s parking supply is still underpriced. If parking spots were priced at the city’s true ideal value, finding a parking spot wouldn’t take longer than the time it takes to drive a few blocks because there would be one available on every block and paying up to $20 for the privilege of avoiding that wait would seem laughably unnecessary.

“People leave from parking spots every day, we just want to make that moment a valuable moment for them,” MonkeyParking CEO Paolo Dobrowolny told the Huffington Post. “We are just providing a way to sync drivers looking for parking and people who are about to leave a parking spot. We are not dealing with the parking space itself which belongs to the city and will be regularly [paid] through the metered parking.”

The criticisms of MonkeyParking, which were myriad, are primarily that the app could push up the price of parking and make San Francisco even more of an expensive playground for techies than it already is and that the app will have the ultimate effect of privatizing space that ostensibly belongs to the public.

.@MonkeyParking you are everything that is wrong with tech and everything that is wrong with with what is becoming of San Francisco.

— Alex Halpern (@HalpernAlex) May 1, 2014

.@MonkeyParking er, you are not reducing traffic, you are just exchanging a rich parking-cruiser for a less-rich parking-cruiser.

— midendian (@midendian) May 3, 2014

Plan to disrupt @MonkeyParking. Sell spaces too small for the cars that want them. Plan B: sell spaces in North beach during towing hours.

— Gordon Elgart (@Dorgon) May 6, 2014

By selling information about what parking spots are available, MonkeyParking gives private individuals both the ability and incentive to squat on parking spaces, waiting for an attractive offer to vacate, and thereby constricting the parking supply.

On one hand, MonkeyParking is just soaking up revenue forfeited by city officials who price parking meters too low, but its effect could be far more pernicious in parts of the city where street parking is free. In these typically more residential neighborhoods, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency has prioritized allowing people who live and work in those areas to stay for long periods of time over collecting rent on its street real estate.

MonkeyParking flips that equation and allows every single parking spot in San Francisco, regardless of city policy towards the area in which its located, to be turned into a commodity.

Whether all of this is legal is another question entirely.

San Francisco recently reached an agreement allowing the private shuttle buses of tech companies to use public bus stops in exchange for a small fee, but that issue was far more clear cut. Passengers were alighting from these shuttles in zones where private vehicles were supposedly prohibited from stopping. The shuttles’ deal with the city simply gave them temporary access to the bus stops. But here, what’s being sold isn’t access, it’s information—specifically, information that the the city transportation agency doesn’t necessarily hold a monopoly on.

Gabriel Zitrin, a spokesman for the San Francisco City Attorney’s Office, told the San Francisco Chronicle that they’re in the process of looking into ParkingMonkey’s legality. “So far,” he said, ?all we’ve determined for sure is that it’s extremely weird.”

In his book Who Owns the Future, computer scientist and author Jaron Lanier talks about entities called ?siren servers”—computer systems that collect data and then take advantage of information asymmetry to monetize that data for their own personal profit. Lanier argues that the primary business model of the current technological revolution is the creation siren servers for every possible informational niche.

Tech behemoths like Google and Facebook are siren servers; but, because most of the information they are collecting and monetizing has to do with private goods rather than public ones, at least on the most obvious level, their true nature is partially obscured.

It takes something like MonkeyParking, which takes a public good like street parking and turns it into a privatized commodity to render the image of a budding siren server into stark relief.

In places where it’s free, or priced low enough to avoid being prohibitive, street parking is something that intuitively seems egalitarian. It doesn’t matter if you’re driving a brand new Bugatti or a 1992 Geo Metro, whoever finds an open parking spot first gets to park there. MonkeyParking has the potential has the potential to change that equation in a way that seems unfair

Siren servers don’t care about things being unfair because fairness, at least in the idealized abstract, is the province of government regulators, not companies like MonkeyParking. Its ability to use information to circumvent those conceptions of fairness is precisely why MonkeyParking is a perfect representation of everything that people both love and loathe about technology in 2014.

Photo by Paul Swansen/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)