At some point in the future, your bandage might do a lot more than just cover up your wound. Researchers at MIT have developed a malleable hydrogel that they can embed with sensors and apply to injury sites.

Xuanhe Zhao, an associate professor in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, has been working on creating a hydrogel that could be stretched and fitted to bond to other surfaces.

“Human tissues are soft and wet, but electronic devices are mostly hard and dry,” Zhao told the Daily Dot. “We propose to use hydrogels with similar mechanical and physiological properties as human tissues to form long-term high-efficacy interfaces between human body and electronics.”

This presented a challenge, as most common hydrogels are brittle and inflexible and don’t adhere to electronic materials. Zhao’s development of a stretchable, biocompatible hydrogel—consisting mostly of water and selected biopolymers—means that other researchers can utilize use the material in previously unimagined ways.

The material achieves a stiffness of between 10 to 100 kilopascals, essentially the same range as human soft tissue, which is crucial for its medical applications.

In a paper published in the journal Advanced Materials, graduate students Shaoting Lin, Hyunwoo Yuk, and German Alberto Parada; post doctoral student Teng Zhang; Hyunwoo Koo from Samsung Display; and Cunjiang Yu from the University of Houston collaborated with Zhao to embed electronics into the more workable hydrogel.

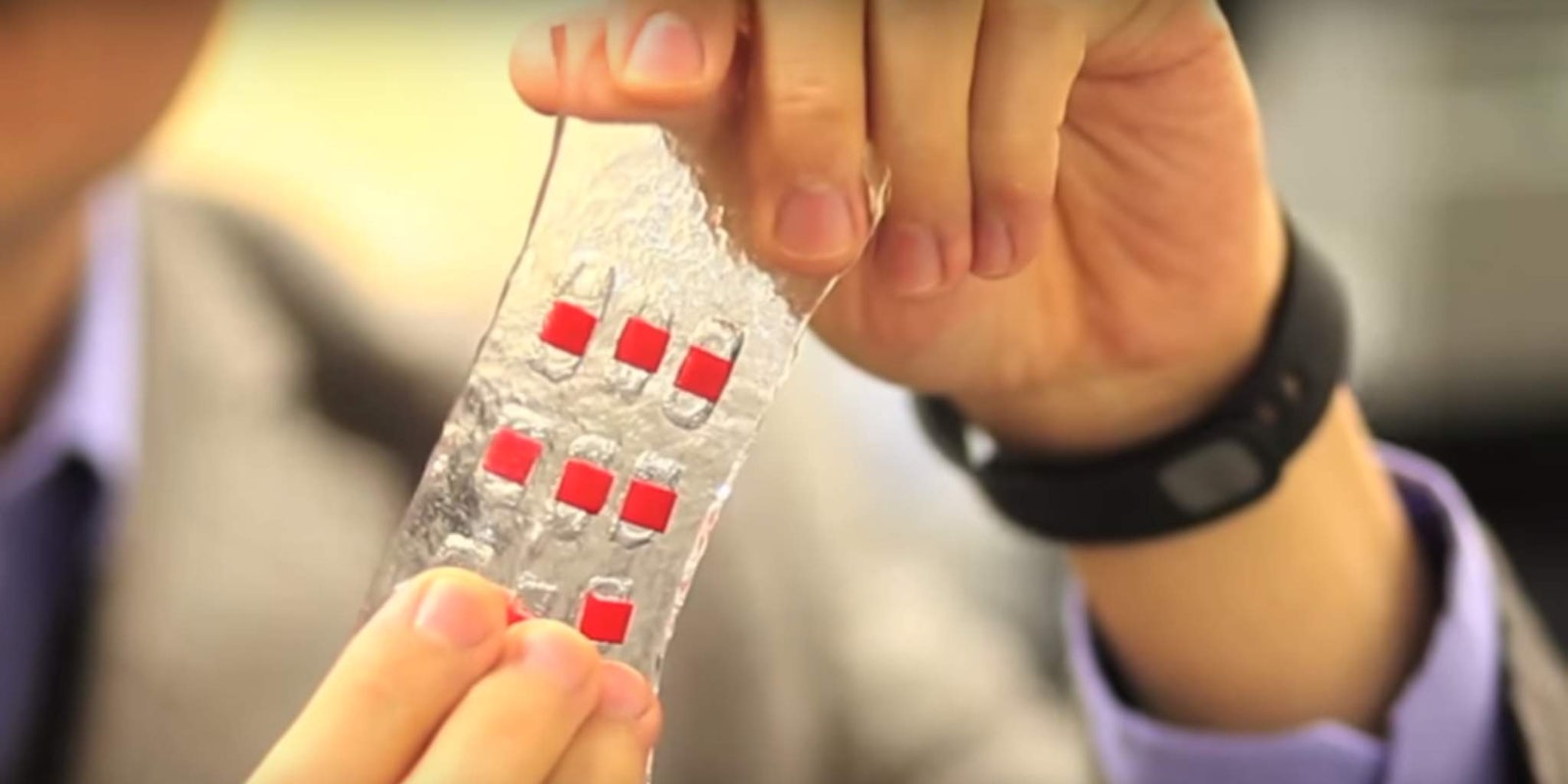

Researchers were able implant a variety of electronic parts into a block of the material, including semiconductor chips, LED lights, conductive wires, and body-measuring sensors.

Building on that achievement, the group created an advanced wound dressing that could fit over nearly any part of the body. The high-tech bandage sported temperature sensors and drug reservoirs that could hold and dispense medication based on data from the sensors.

Zhao said the smart wound dressing could work wirelessly and interface with devices like a smartphone to provide additional information to the wearer or medical staff. The application is reminiscent of Chaotic Moon’s Tech Tats—temporary, sensor-laden tattoos that can be affixed to one’s skin—though Zhao’s work is more about function and less about flash.

The technology could find immediate applications in treating burns or surface-level conditions. But Zhao sees the future of the hydrogel as being subdermal—below the surface of the skin.

Because of the hydrogel’s biocompatibility, it could potentially deliver electronics to the interior of the body. “We are working on hydrogel matrices and coatings for implantable devices such as glucose sensors,” Zhao said.

Other researchers at MIT have also been searching for a way to get sensors inside the body. One such effort resulted in a swallowable sensor that can measure vital health signs from inside the body, revealed in a paper in the journal PLOS ONE in November.

Zhao is also looking at the human head as a possible area of exploration. He explained that his hydrogel would be ideal as a carrier for neural probes. To that end, he and his team are working with others to create “hydrogel-based neural probes that possess similar mechanical and physiological properties as [the] brain.”

Earlier this year, a team of MIT researchers described a new method of neural probing in a paper published in Nature Biotechnology. The approach called for a soft, fibrous, non-invasive material that could essentially integrate itself as a part of the brain itself.

While much of this technology, including Zhao’s hydrogel, is still in the early stages of development and testing, it appears more and more inevitable that, at some point in the future, something developed at MIT will end up inside of you, fine-tuning your body and letting you monitor its progress on your smartphone.

Screengrab via Massachusetts Institute of Technology/YouTube