Usually when you hear “worm” used when it relates to technology, it refers to malware, but researchers at MIT found the inspiration for their latest creation from the real kind.

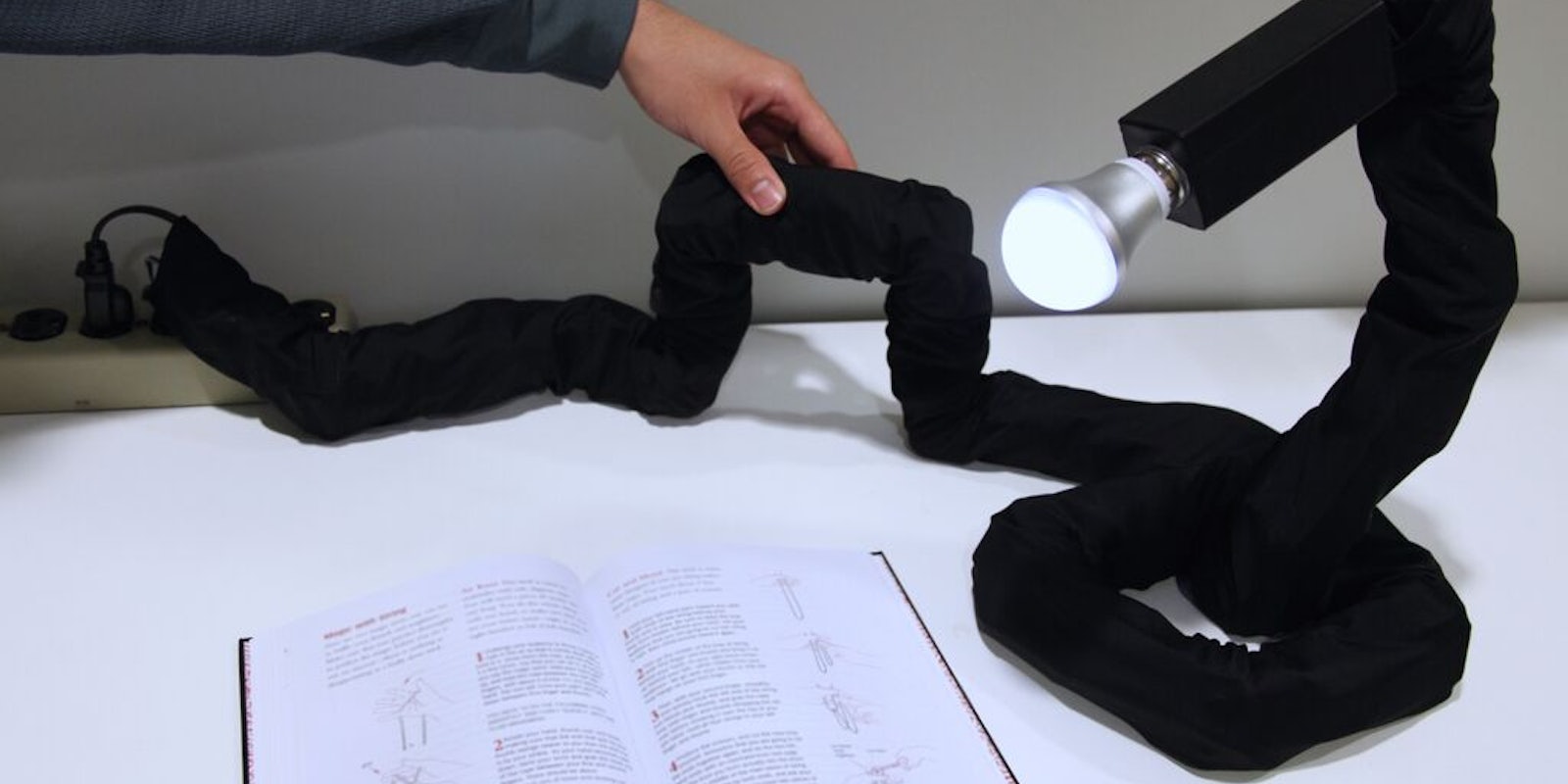

The device, dubbed Lineform, is a slithering, shape-shifting soft robot capable of handling a wide variety of common tech-related tasks. Designed by MIT Tangible Media Group, the serpentine-style peripheral is a reimagining of cords and wires if they could come to life.

Ken Nakagaki, an Interaction Designer at MIT Media Lab, told the Daily Dot that he was thinking of a new shape-changing interface after joining the group last year. He settled on about as simple a shape as is imaginable: a line. “The origin of the idea was coming from the notion of daily line-based materials such as string, wire or rope,” he said.

“A lot of questions came up in my mind. ‘What if these material can transform to any kind of shape? How would our computer or tools around us change? How can we design interaction with such material?’ Through investigating the possibility of such material, we realized that the form of ‘line’ can play a quite impressive role,” when it comes to interfaces.

The foundation for Lineform comes from other snake robotics technology. Thin, flexible bots have previously been presented as an option for medical procedures, placing a microscopic camera in places that would otherwise require invasive surgery to see. Snake-like characteristics have also been the inspiration for other bots that could be used for search-and-rescue or exploratory operations to navigate challenging terrain and tight corners.

Using the existing technology as a starting point, the researchers at MIT crafted the Lineform prototype.

“The hardware consists of a series of motors so that the overall shape can be rendered by controlling each motor’s angle,” Nakagaki said. The motors are controlled by an Arduino Mega microcontroller board, and the entirety of the bots’ mechanical guts are covered by a black spandex skin.

Don’t worry, despite its similarities to a snake, Lineform doesn’t shed its skin—in fact, it counts on pressure sensors embedded in the spandex to detect touch data.

Nakagaki refers to Lineform as an “actuated curve interface” that has a plethora of potential applications. Because of its unique ability to change shape on the fly, Lineform can be anything from an expressive data cable that shimmies to show the data moving through it to a high-tech stencil that can form any shape.

Nakagaki suggested it could do anything from simulate a smartphone-style touchscreen surface that can be tapped and swiped, to form itself into the shape of a phone and be used to make calls (with the proper technology wired in, of course).

Nakagaki said he and his fellow researchers developed two different prototypes with different sets of specifications and sensors equipped to each. “Having prototypes with different specs, we intend to show a wide range of possibilities for the actuated curve interfaces,” he explained.

While Lineform is the latest work to come out of the Tangible Media Group, the team has been hard at work for several years to create new ways for people to interact with technology.

Driven by a vision to “seamlessly couple the dual world of bits and atoms by giving dynamic physical form to digital information and computation,” the researchers under Professor Hiroshi Ishii previously created a display that can render virtual content physically so users can tangibly interact with digital information. Earlier this year, the group revealed Social Textiles—shirts that display information about the wearer and connect people with similar interests.

Lineform goes well beyond the Tangible Media Group’s previous works. In the paper detailing the device, the researchers note they specifically chose not to detail the implementations they came up with in hopes of inspiring further research and development for the technology.

There is just one major problem facing Lineform; as a device predicated on improving how people interact with technology, it has to actually get people to want to interact with it. When researchers demonstrated the device, they found it would often “startle users when it quickly changes form.”

That’s perhaps not all that surprising, given how common a fear of snakes is; some research suggests one in every three adults suffer ophidiophobia, the fear of snakes. According to a study published in Biological Psychology, there is evidence to suggest that a fear of snakes is an evolutionary association—the human brain is just wired to dislike snakes.

Nakagaki said that’s an issue they plan on addressing. “Further research on designing comfort motion or utilizing soft actuators might be required so that user would not be afraid to directly interact with them,” he said.

H/T Gizmodo | Photo via MIT