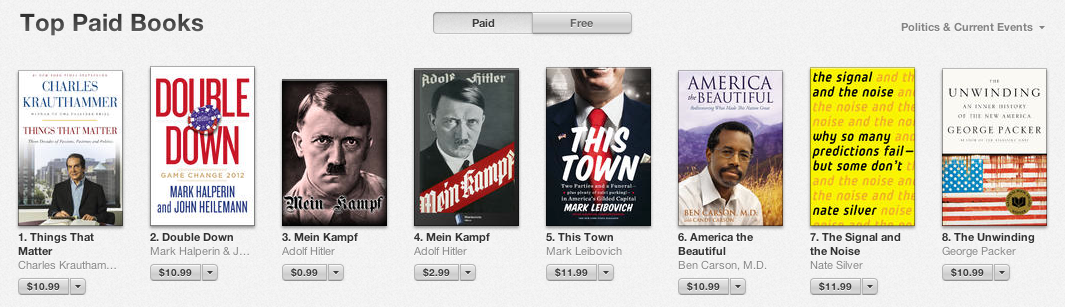

Not many people are willing to break out a paperback copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf on the subway, but a fair number are buying ebook editions to read on anonymizing tablet devices like Kindles or iPads. Downloads of the vile Nazi manifesto have been topping iTunes and Amazon sales charts for a year, despite the wide availability of free English translations online.

“Mein Kampf hasn’t made The New York Times nonfiction chart since its U.S. release in 1939,” author Chris Faraone noted in a post on Vocativ, and print sales slackened over the following decades. They still haven’t bounced back, but cheap digital versions are doing just fine, possibly buoyed the same dread that made 1984 a bestseller in the wake of last year’s NSA revelations:

On Amazon, there are more than 100 versions of Mein Kampf for sale in every conceivable print and audio format, from antique hardbacks to brand-new paperbacks. Of those 100 iterations, just six are e-books—yet all six of them rank among the 10 best-selling versions overall.

Part of the book’s prominence on these websites—especially when compared with the display table at your favorite indie bookshop—surely has to do with its unclassifiable nature: it turns up in lists of popular historical or WWII texts as well as autobiography sections, and even in Amazon’s “Propaganda & Political Psychology” and “Legal Thrillers” search fields.

Nevertheless, its recent surge in popularity appears to be tied to the proliferation of ebook editions, which in turn looks to be generated by significant demand for a way of reading a gargantuan racist screed by Hitler without advertising one’s interest or lugging around a three-pound book. But that remains a chicken-or-the-egg equation.

Could it be, as Faraone suggests, a phenomenon related to the mindset that made 50 Shades of Grey the first ebook with a million Kindle sales? It’s widely believed that the kinky erotic novel is something people don’t want to be caught reading (or spend much on)—thus the “clandestine” option prevails. That could explain why ebooks of Mein Kampf outsell print editions, but it does little to illuminate rising public curiosity about Hitler’s dense, repugnant, paranoiac theories.

There’s just as good a chance, in fact, that these numbers reflect something about ebook readers themselves: perhaps they’re more willing to explore the taboo fringes of prose. In any case, the notion that there’s anything “private” about beaming Hitler’s words directly into your tablet is misguided, as Richard Lea notes in the Guardian: user agreements ensure that companies have a clear picture of your purchasing and reading behavior.

Hand-wringing as to who may profit from such success is a given (Random House, which holds a U.K. copyright, has donated more than $1 million to the Holocaust Survivors’ Memoirs Project), but the ebook revolution has been a boon to hate speech overall. Even in Germany, where production of Mein Kampf is illegal, it’s just a click away for anyone with Internet access.

H/T Vocativ | Photo by Ronnie Bell/Flickr