In order to protect us against cybercriminals, security researchers—or white hat hackers, as we also call them—often have to engage in activities that could be considered criminal behavior by law enforcement. Such might be the case of Marcus Hutchins, the accidental hero of past May’s WannaCry outbreak, who was arrested by the FBI last week after attending the DefCon security conference in Las Vegas.

The 22-year-old British security researcher is being charged with developing the banking trojan Kronos and attempting to sell it to criminals between 2014 and 2015. While Hutchins might be guilty of the crimes he’s being charged with (white hat hackers getting involved in criminal scams is not without precedent), it can also be a total misunderstanding of his intentions and goals, as some experts have pointed out.

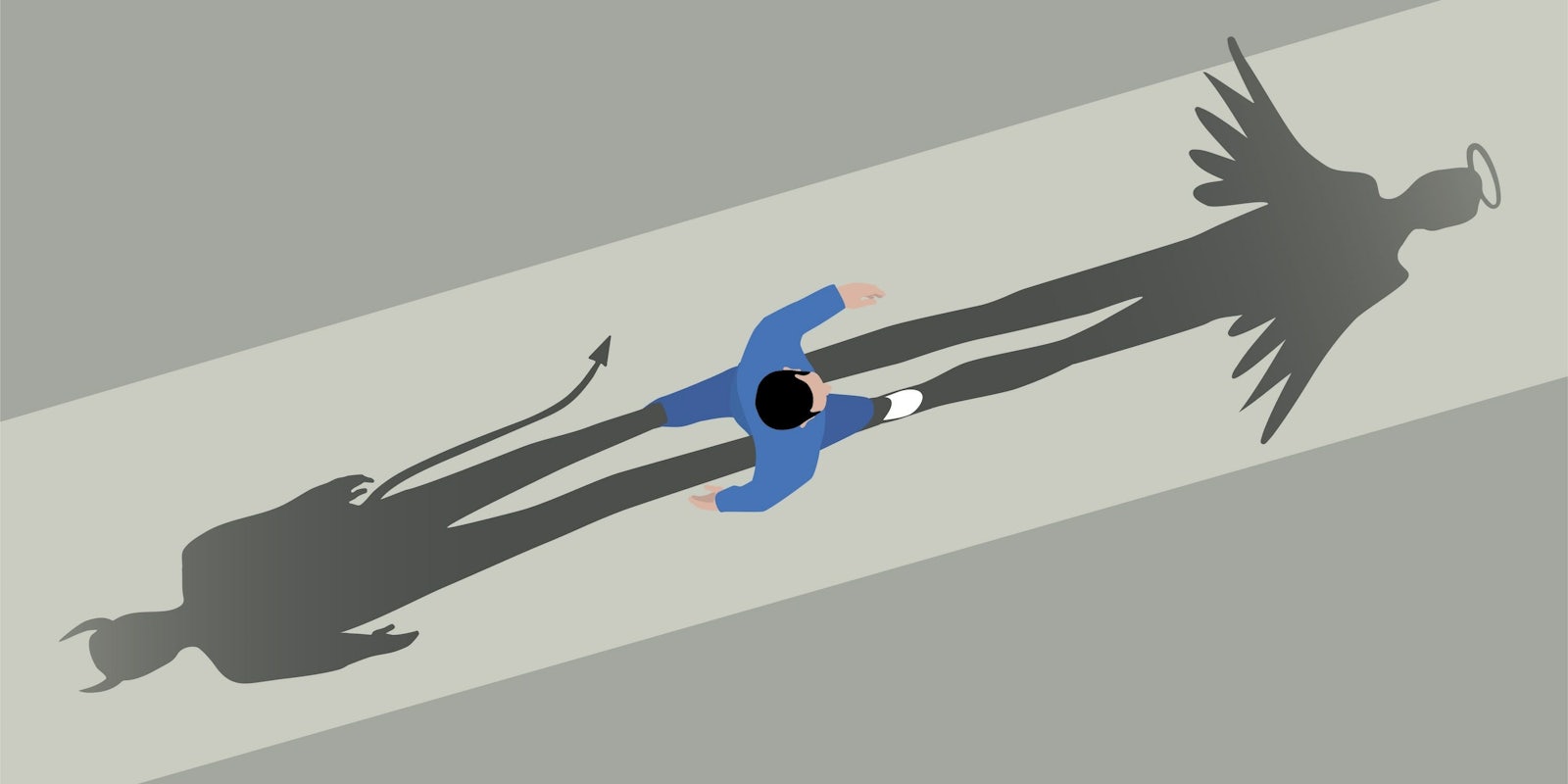

Researchers often have to write malicious code and compromise the security of software and networks in order to find and fix flaws and vulnerabilities or prevent damage from propagating.

For instance, in late July, when cybercriminals were exploiting a coding vulnerability in an Ethereum application to drain funds from cryptocurrency wallets, a group of white hat hackers took it upon themselves to save the day—and $208 million worth of tokens and coins—by hacking the same wallets through the same vulnerability and funneling the funds to the group’s wallet before the hackers could reach them. The saved money was returned to its respective owners after the bug was fixed.

Because of the nature of the job, security researchers always live in fear that their actions will be misinterpreted by authorities and the companies whose products and services they investigate.

They will also have to deal with the consequences of others putting their code and tools to evil use. In 2009, a coder at Morgan Stanley was sentenced to two years in prison because a network monitoring tool he had developed ended up being used in criminal activity.

Hutchins was evidently aware of the dangers involved in being a white hat hacker. In a blog post published in 2014, titled “Coding Malware for Fun and Not for Profit (Because that would be illegal),” he wrote, “A while ago some of you may remember me saying that I was so bored of there being no decent malware to reverse, that I might as well write some. Well, I decided to give it a go and I’ve spent some of my free time developing a Windows XP 32-bit bootkit. Now, before you get on the phone to your friendly neighborhood FBI agent, I’d like to make clear a few thing: The bootkit is written as a proof of concept, it would be very difficult to weaponize, and there is no weaponized version to fall into the hands of criminals.”

But law enforcement isn’t the only worry of white hats. Security researchers often become the victim of hackers whose plots they foil. An example is Brian Krebs, a researcher and investigative cybersecurity journalist who has played a prominent role in exposing criminal rings and scams. Krebs has been the target of several attacks, including against his website, his home, and his person.

For these very reasons, a large number of security researchers take up aliases and avoid revealing their true identities. Hutchins was known by the aliases MalwareTech and MalwareTechBlog before being exposed by British tabloids. However there’s no direct evidence that the exposure had anything to do with his arrest, and there’s a likely chance that it was linked to the shutdown of the AlphaBay dark web market, where the Kronos malware was sold at the time of Hutchins’ alleged crime.

In recent years, lawmakers and regulators have tried to help protect cybersecurity researchers and analysts, but the results have so far been limited, and there’s fear that lack of support will prevent them from performing their invaluable functions.

But white hats have proven that they aren’t afraid to walk the fine line between crime and heroism. For the moment, it remains to be determined exactly which side of that line Hutchins, who will be appearing in a Milwaukee court on Aug. 14, truly stands.