John Draper fiddles with the mouthpiece of the little blue box on the table, blowing into it over and over again. It’s 1972, and a nervous Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak look on anxiously, hoping he can make their makeshift device work. If he’s successful, they’ll be able to call anywhere in the world for free, manipulating the complex phone system with little more than a series of perfect tones. This is Draper’s gift to the world, and his curse.

Wozniak and Jobs only know Draper by his notorious pseudonym, Captain Crunch, the elusive character at the center of an underground subculture of rebel hackers called the phone phreaks.

Tilting the device’s mouthpiece and mumbling about Wozniak’s digital redesign, Draper finally gets it to work. He asks who they want to call first. Wozniak doesn’t hesitate: the Pope.

Huddled around the blue box in a darkened student dorm at the University of California, Berkeley, the group dials out to Vatican City. After several attempts, the call goes through. It feels like magic. Draper holds out the handset to Wozniak just as someone answers on the other line.

“This is Henry Kissinger, I must talk to the Pope right away. I must confess my crimes,” Wozniak declared, Draper recalls decades later, his voice cackling.

“Sir, but the Pope isn’t here right now,” a confused clergyman allegedly replied. “It’s four in the morning in the Vatican. The Pope is sleeping. Just one moment.”

Draper, now 74, pauses and grins as he recounts the story. He looks slightly disheveled, with a wiry gray beard, unassuming.

Wozniak and Jobs, of course, would go on to found the most successful tech company in the world. But Draper is far from being just an important footnote in Apple’s history. He’s the original hacking prankster, a purist driven by curiosity and craftsmanship, with a lifetime of exploits that have pushed technological and legal boundaries. And according to Jobs, in a rare 1994 interview, without him there wouldn’t have been Apple.

Now, for the first time, Draper is looking to publish his story with Beyond the Little Blue Box, an autobiography for which he’s about to launch a Kickstarter campaign.

After a beat, Draper picks back up the story, drawing it out with his low nasal rasp: Another, more suspicious voice came on the line. No one was sure what to do or what it meant. Wozniak panicked and killed the connection.

Phreaks and geeks

Draper’s just returned from a mid-afternoon training session at his local gym in Las Vegas. He’s been trying to get back in shape after having a major back surgery that was, in large part, crowdfunded by his fans and followers.

He rocks back in his chair and retells how he anonymously called in a national emergency directly to a furious President Richard Nixon on the Oval Office phone line, reporting that the West Coast had run out of toilet paper. He also claims he once bypassed the Iron Curtain to call Moscow in the Soviet Union.

There’s a playful mischief about him, but he’s serious when it comes to his craft, relaying technical, intricate details about the systems he worked to hack.

At the time, the automated control signaling system used nationwide relied on tonal frequencies to identify unused long-distance lines. In 1957, Joe Engressia, a blind hacker better known as Joybubbles, discovered that whistling a high-pitched tone of 2600Hz (a seventh octave E, musically speaking) would reset the line, ultimately allowing the user to make free phone calls.

More than a decade later, after leaving the Air Force in 1968, Draper was taught Engressia’s telephonic magic by a mutual friend, a blind teenager named Dennis Teresi.

“I was really fascinated by the fact that you could inject tones into the phone,” Draper recalls. “I couldn’t believe that the phone companies were that stupid to make it so easy to make these calls. It worked everywhere, that’s the thing about it. It worked everywhere!”

Up until that point, most phone phreaks who couldn’t whistle at 2600Hz instead utilized a toy whistle given out in Cap’n Crunch cereal boxes that just happened to hit that perfect tone. Knowing that Draper had been an engineer, Teresi encouraged him to build his own device that would remove the toy from the equation.

Adopting the name Captain Crunch, Draper’s first blue box consisted simply of an electronic audio oscillator (to produce the all-important tones), a speaker for the phone’s mouthpiece, and a telephone pad.

To use a blue box, a phreak would normally dial an unsupervised 800 number and trigger the blue box to emit a 2600Hz tone into the handset’s mouthpiece, imitating the steady signal used by the phone company to determine that the phone was on-hook and not being used. The technique would reset the line, indicated by a high-pitched cheep, leaving the caller on with a tandem switching circuit. At that point, the phreak would dial a routing command and phone number using the blue box’s multi-frequency tone telephone pad.

At the time, AT&T owned a monopoly on public telecommunications, and the average subscriber’s phone handset had limited touch-tone technology that prevented it from dialing this way. Multi-frequency tones were the reserve of operators and company engineers. With them, calls could be placed domestically or internationally for free. Essentially, Draper and others figured out how to bypass those operators.

“My own blue box only had six push buttons. I didn’t have enough notes to make a dial note so I had to press two buttons at a time to make a number. I just wanted to see if it’d work and, oh my, it worked. I was bouncing against the walls, man,” he remembers. “My parents thought I had gone mad, back and forth between the piano and my room making sure the frequencies were spot on.

“I was just interested in understanding the technology,” Draper continues.

The phreaking community at the time was limited to only about 50 or 60 people. Then, overnight, everything changed.

The Esquire exposé

In October 1971, Esquire magazine published an investigative feature that changed Draper’s life forever. Written by a young journalist named Ron Rosenbaum, “The Secrets of the Little Blue Box” revealed the hacker subculture of rebel teenagers and tech enthusiasts who hacked the phone system to explore its reaches and connect with one another.

The phone phreaks, Rosenbaum explained, would meet on hidden conference lines using quirky nicknames to discuss ideas and hacking techniques. Draper featured heavily as the pseudonymous Captain Crunch, an eccentric genius who lived out of a Volkswagen camper-van that he’d loaded up with phone-switching equipment.

“I was at San Jose City College going through one of my courses and I missed my physics lab class. I had to read it all,” Draper recalls when asked about the first time he read the piece. “Reading it, I remember thinking that this article would end phone phreaking as we knew it. It would have a lot of heads turning—the authorities, the government, the phone company. I knew then that this was very serious.”

As far as the phone phreaks were concerned, their technology and methods merely utilized a vulnerability in the system. To AT&T, the phone phreaks were fraudsters, a criminal menace and a threat costing the company millions.

“Just days after Esquire published, the phone company got together with the district attorney and they started listening in on calls,” Draper claims. “They discovered the 2111 conference by tapping the lines.”

The 2111 conference line was an unused Canadian Telex phone line that a core group of phone phreaks discovered, a testing trunk line that was permanently open. It became a space for them to congregate and share ideas, codes, and hacking techniques.

“Only the elite and knowledgeable people were there; this was serious stuff and where some big discussions happened,” Draper recalls.

Once the authorities had access to the 2111 line, it was open season.

“I jumped in on the line just to hear what was going on. It was clicking, popping, people were getting knocked off,” Draper recalls.“They started busting people, right and left.”

‘The whole world in his hands’

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak also read the Esquire piece, and they became determined to track down Captain Crunch.

Wozniak, then a third-year student at the University of California, Berkeley, became consumed by phone phreaking after picking up his parents’ copy of the magazine. He had immediately called Jobs, then a 17-year-old high school senior, to tell him about it. They even came up with their own phreaker pseudonyms—Berkeley Blue and Oaf Tobar, respectively.

The following Sunday, the pair headed straight to Stanford Linear Accelerator Center to dig out old books on phone technology. There, in a tome on telecommunication standardization, Wozniak found the complete list of tonal frequencies needed to dial out a number. Wozniak used the book to build his own digital blue box, but he couldn’t get it to work. They needed Draper.

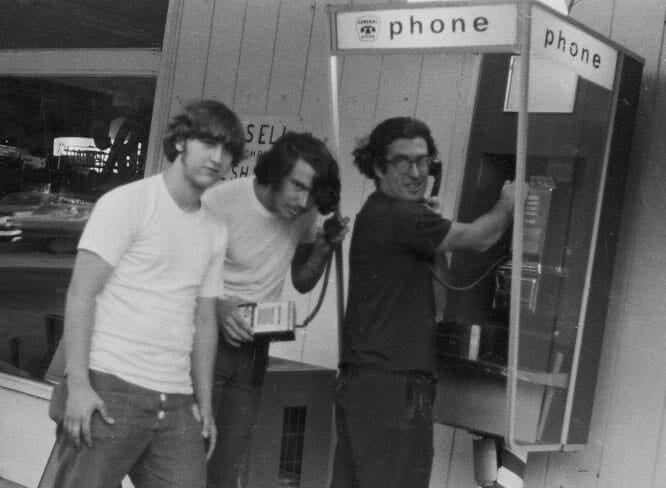

As luck would have it, Captain Crunch was interviewed shortly after by the KPFA radio station. After several calls, they made contact, and Draper offered to meet Wozniak at his University of California campus dorms to show him how to work the blue box.

“I was there with Wozniak, Jobs, and with Bill Klaxton, when he showed me the box. I looked at the box and thought, ‘this can’t be,’” Draper recalls. “I offered to try it, naturally, but I told them it wasn’t going to work.

“He had made a digital box which, using digital electronics, produces square waves. Inputting these into an analog system would make a lot of noise and could get him busted. After manipulating the mouthpiece a little, we were able to get it to go through. That’s when we called the Pope.”

The three continued to meet regularly at a pizza parlor in Berkeley to learn code, often sitting together long past midnight. The entrepreneurial Jobs suggested that they begin to sell the blue boxes for profit, and they did—without Draper.

“I told him it would get him into trouble, me into trouble, everyone into trouble,” Draper recalls. “He said not to worry about it; they wouldn’t mention me. They were making them and selling [them] to all their buddies in college. Each little blue box sold had a note inside which read, ‘He’s got the whole world in his hands.’”

Each blue box unit was sold at around $150 and, oddly for an illegal hacking device, a warranty. The demand was high, according to Wozniak. He had refined the design, even improving the battery life—work that to this day, even having since built several of Apple’s groundbreaking computers, he says is his among his best. As Wozniak manufactured the boxes, Jobs helped establish a distribution network stretching to Los Angeles, but after a close encounter with the police, the two put their phone phreaking days behind them.

“Over time, I liked seeing Draper every few months to hear more about these unbelievable phone tricks that they could turn into movies one day,” Wozniak tells the Daily Dot. “Jobs started avoiding Crunch, however, afraid that it would put us too close to getting arrested. And Jobs didn’t have a feeling for what I saw as good, the exciting and entertaining knowledge that Draper had of ways to do impossible things.”

Jobs was right, in a sense: The FBI was closing in on Captain Crunch.

Prison and other problems

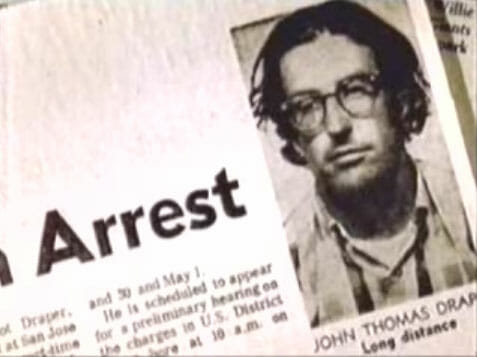

John Draper was arrested by the FBI for the first time on May 4, 1972. He was charged with seven counts of wire fraud, under 18 USC 1343, and given a five-year suspended sentence. In its report, phone phreak historian Phil Lapsley notes that the San Francisco Chronicle hailed Draper as a “contemporary folk hero” and “an overgrown, misunderstood kid with the mind of a genius.”

A parole violation in 1976 related to his original 1972 wire fraud charge landed Draper in Lompoc State Penitentiary in California for a four-month stint.

“I ended up spending quite a bit of time in the library, giving phone phreaking classes—right in front of the guard’s noses,” Draper says with obvious pride but a hushed voice, as if concerned the guards still might overhear. “I taught other inmates some of the vulnerabilities I knew of. I made sure by the end of my ‘courses,’ that all my students could draw a schematic, calculate resistor values, and build and test them.”

Draper had been a member of the Homebrew Computer Club, a hobbyist group that had attracted hackers and engineers alike, including Wozniak and Jobs. But while he was inside, the computer revolution was beginning without him: As Draper headed to Lompoc, Wozniak had just finished the Apple I computer.

Upon his release in 1977, Wozniak hired Draper to work as an independent contractor on the Apple II, a chance to turn things around. He designed the Charlie board, a prototype attempt at a modem almost a decade before that technology came to the fore. Jobs didn’t like it and, with AT&T in sole control of consumer phone technologies, there was no market. The product was dropped.

“John is like a creative artist-inventor. He comes up with programs and approaches that are so new, they don’t always fit into product needs,” Wozniak says of Draper’s work. “But they are outstanding on their own.”

In 1978, Draper went to prison again, followed by another stint in the Alameda County jail in 1979. It was there Draper wrote what would become the first word-processing program used in the Apple II, EasyWriter—named after his favorite movie, the counterculture classic Easy Rider. The entire code was written on paper and researched while he was on furlough. On his release in July 1979, he signed the commercial contract with Information Unlimited Software, which had offered to market EasyWriter. Draper then beat Microsoft Mogul Bill Gates in delivering a ported version of the word processor to IBM for use in its first marketed personal computer.

Despite his success, Draper struggled to get work. Many industry professionals, including Jobs, were wary of him because of his convictions. Very few, like Wozniak, appreciated that his talent as an engineer might eclipse his criminal record. Out of work and out of luck, Draper largely disappeared.

A different kind of legacy

In the mid-’90s, Draper stumbled into another hacker subculture movement.

In 1992, unemployed and living in his brother’s spare room in San Francisco, he met Phil Zimmerman, the rebel cryptographer and creator of Pretty Good Privacy, or PGP. He became part of an email forum called the Cypherpunk Mailing List that discussed cryptography and met regularly in a back room at Cygnus Solutions to discuss privacy issues. He became a privacy advocate, preaching the value of encryption at rave events and helping people implement PGP, and he’s been doing it ever since, regularly speaking at privacy and open-internet events throughout the world.

More recently, he’s redirected his activism, driving social media campaigns for both imprisoned Russian Tor node operator Dimitry Bogatov and Marcus Hutchins, the British security analyst credited with temporarily stopping the WannaCry virus, who was indicted in August for unrelated computer-hacking charges.

“I recently had a one-on-one conversation with Kim Dotcom,” Draper interjects, speaking of the founder of Megaupload. “I was really surprised to learn that Kim had heard about me a long, long time ago. I’m a fan of Kim, and Kim is a fan of me.”

Imprisonment and prosecution have spurred an affinity in Draper for those testing technological boundaries, those willing to confront law enforcement and major corporations for the sake of playful experimentation and progress.

“I care about people who get wrongly accused, you know,” he says.

For many tinkering young coders and internet activists, Draper is still considered a folk hero, one whose apolitical infatuation with complex systems and compulsion to expose their limits made him a target—especially where that curiosity crossed with corporate interests.

But although largely snubbed by Silicon Valley—his last formal position within a company was at Autodesk in the late 1980s, though he’s done some freelance web development—Draper exhibits no regret or bitterness. He doesn’t wonder where he might have been had he made different decisions. He instead embraces the generosity of friends like Wozniak.

“Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers,” Draper’s old colleague, Steve Jobs, read in one famous Apple advertising campaign. He could’ve been describing Draper. In fact, in a rare 1994 interview, Jobs explicitly cites the blue box business as a formative period, an essential but off-brand prelude to Apple.

“Experiences like that taught us the power of ideas,” Jobs said. “The power of understanding that if you could build this box, you could control hundreds of billions of dollars around the world, that’s a powerful thing. If we hadn’t have made blue boxes, there would have been no Apple.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxCNvNwl60s

Wozniak revisits the question: “Would Apple exist without John Draper?” he asks.

“It’s hard to guess. Steve Jobs said—and I agree—that without the blue box there might never have been an Apple,” Wozniak says. “A lot of people have success and make money, but fewer achieve notoriety and fame like John has.”