A woman wearing an elegant red dress steps onto the stage in the center of the arena. She takes out cue cards and says a few words into the microphone, prompting four men in military-ready outfits—tight black shirts, green cargo shorts, and aviator sunglasses—to emerge and line up on beside her. They’re holding automatic rifles. Suddenly, they turn and march toward large platforms that look like teleportation machines from the future.

Roughly 11 million viewers are watching around the world on smartphones and laptops, anxious to see what happens next. You can feel the tension building.

Within minutes, the men will be battling in a virtual reality world, venturing through a shipyard and gunning down enemies. But first, they have to strap in: Two thick bands lock them into position on an omni-directional treadmill, which transports their physical movements into the VR world.

The contrast between what viewers are witnessing on the Jumbotron—a gripping battle between trained assassins—and what they’re seeing in real life could not be more jarring. The professional gamers sound like clumsy tap dancers as they clack up and down the sides of the platform, firing at objects only they can see.

This is the scene of last year’s Hero Pro League Finals, a Shenzhen, China-based esports competition for the first-person shooter Crisis Action. For the first time, the esports event was played with the Virtuix Omni—a niche device in a niche industry—and, in many ways, it represents a bold new chapter for VR gaming.

It’s just not the one that its creator imagined.

In 2011, Jan Goetgeluk made a contract with himself. He was working 80 to 100 hours a week at JP Morgan, the world’s richest investment banking firm, but in what little spare time he could manage, he was chipping away an early prototype of the Omni using old Vuzix 9000 glasses. One day he uploaded a video of himself playing a VR version of the popular open-world game Elder Scrolls: Skyrim with the device.

“It got 200,000 views on YouTube in a day, and I got a huge press cycle out of it, lots of excitement,” Goetgeluk recalls, the enthusiasm still present in his voice. “And that’s when I thought, you know what, I think this is it.”

Goetgeluk decided then that in three years, he would quit his lucrative job and build a startup, Virtuix, from the ground up. It seemed like a natural next step, given his lifelong obsession with gaming.

Goetgeluk grew up outside of Ghent, Belgium. He credits his father, a salesman and “first mover,” for his early obsession with technology.

“We were the first ones to have a Gameboy, first ones to have a Nintendo, first ones to have a PC back then,” said Goetgeluk, who got his master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Ghent before moving to Houston, where he received his MBA at Rice University.

Goetgeluk remembers running home from middle school to boot up his 486 PC and play early classics like Space Quest, King’s Quest, and Doom. But nothing quite captured his imagination like the LucasArts Indiana Jones titles and their ability to transport people into a new world. It’s that same sense of wonder he wanted to create with the Omni.

For months, he would toggle between investment banking and late-tinkering, often not starting work on prototypes until 2am. With time, he was able to add resources and support to Virtuix.

“Sometimes I would leave the JP Morgan office, and I would drive to the machine shop south of Houston to check on the prototypes, and then I would drop into the office to resume my day job,” Goetgeluk said laughing, as if realizing the extremity of his schedule for the first time.

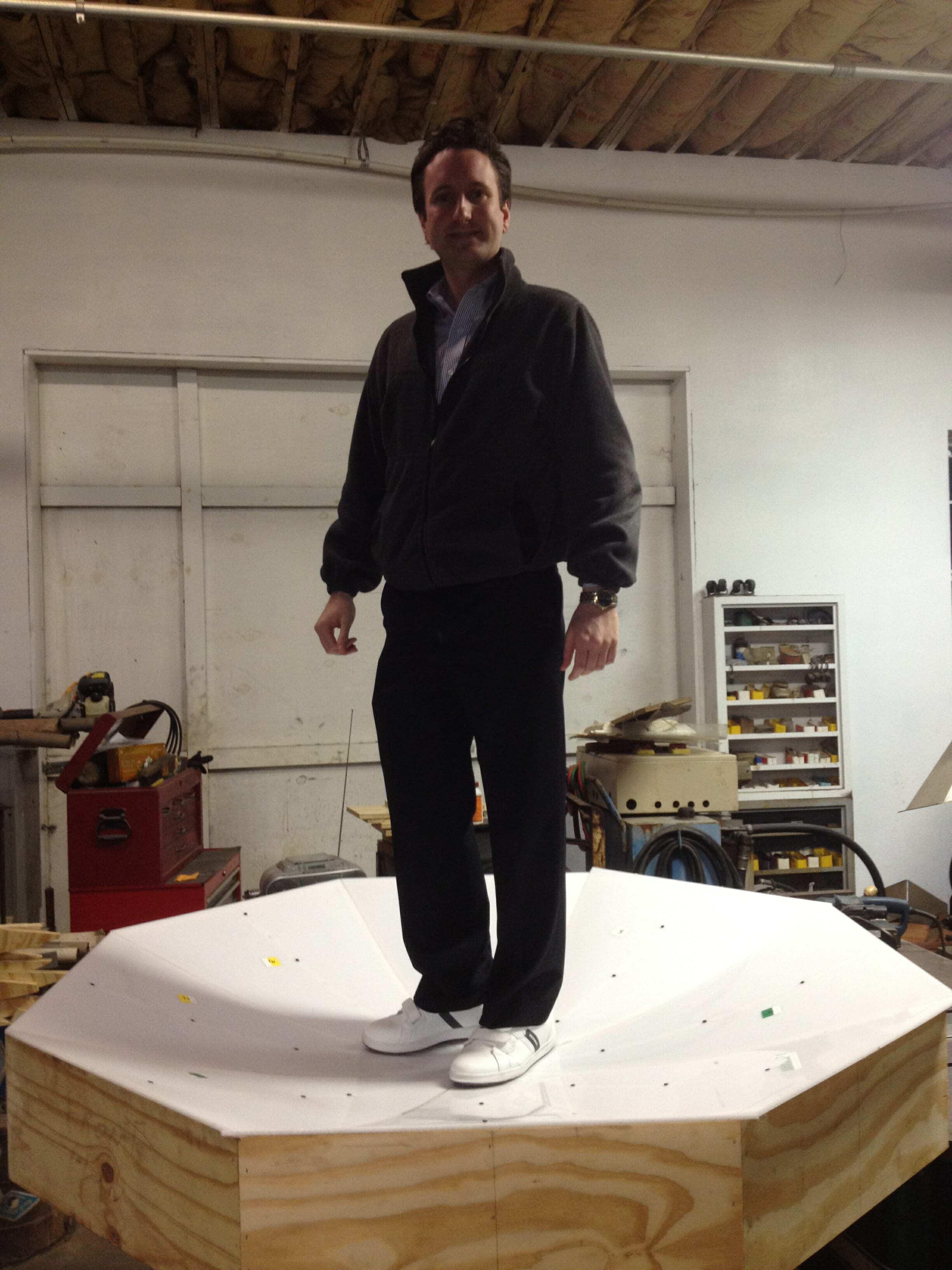

It took months of failed concepts before he settled on a solution he thought could bring locomotion to virtual reality at a reasonable cost to consumers. The final design took the form of a smooth, concave octagonal platform with two large arms and a round center harness.

Despite its intimidating size and science-fiction–inspired shape, the Omni is less technical than you might think. Gamers naturally walk up and down its edges using low-friction shoes with slick plastic bottoms while a circular, waist-high harness keeps them from falling over or losing balance. The rest is left up to some clever software, which takes sensor data, feeds it to a VR headset, and translates movements onto a virtual character.

The Omni can determine when a gamer jogs, sprints, jumps, ducks, or even walks backward. Learning to walk on it is a lot like learning to ice skate: It takes time, but anyone can do it with enough practice.

Goetgeluk was ready to test his prototype on the market.

Fast forward two years: Goetgeluk is in the crosshairs on Shark Tank, offering $2 million for a 10 percent stake in the company. His valuation of Virtuix stands at an audacious $20 million. He’s dressed in a black suit with his hair slicked back, giving his most convincing pitch in national prime time.

Mark Cuban, a noted tech enthusiast, looks intrigued. His eyes widen and lines form on his forehead the moment he hears “virtual reality.” But the other Shark Tank hosts look confused as a Virtuix employee plays TRAVR, an early first-person shooter made specifically for the Omni, in front of millions of TV viewers.

None of the sharks gave Goetgeluk an offer. Not even Cuban, who feared the Omni was too reliant on the success of Oculus.

“I thought they had good reasons why not to do the deal,” Goetgeluk admitted. “It was so early in VR, and for the most part, they weren’t familiar with Oculus or the VR renaissance.”

Goetgeluk had previously found a more receptive audience on Kickstarter. His campaign, with its bold vision of “VR in every living room,” raised $1.1 million in 60 days.

But Goetgeluk soon discovered the Omni was far more expensive to manufacture than anticipated. Little things, like redesigning the door clasp or finding the right material for the shoes, added up. Virtuix’s Kickstarter shipments were delayed a month, then six months, and eventually, a full two years after its scheduled July 2013 ship date.

Those setbacks were only compounded by the industry’s own problems. Despite being perpetually hailed as the next big thing, VR adoption proved much slower than anticipated, due to skyrocketing prices and concerns about motion sickness.

For Goetgeluk, the increasing cost and complexity of building a single Omni led to the realization that the product wasn’t a good fit for homes. In October 2016, despite some continued demand from consumers, Virtuix stopped selling to individual gamers, and the company issued a refund to all of its Kickstarter supporters outside the U.S.

Goetgeluk’s dream should’ve ended there.

Just when it looked like things couldn’t get any worse, Goetgeluk had an epiphany—and some good luck.

His business partner, David Allan, noticed the unexpected rise of VR gaming arcades first-hand in China. Brought on in part by a 14-year home console ban, hundreds of VR gaming arcades had popped up across the country.

“That was not a thing in the Western markets. It was all about the consumer market—Oculus, HTC—it was all about getting VR to the home,” Goetgeluk said. “There were no arcades, the arcade market was dead.”

Instead of trying to bring the Omni to living rooms, he could take it to where there was already demand.

In 2016, Goetgeluk was put in touch with Hero Entertainment, a billion-dollar gaming company and creator of one of the most popular mobile first-person shooter games in China. Hero’s executives wanted to bring its 400 million Crisis Action users to the hundreds of arcades across the country, but it needed an incentive. That’s where the Omni came in, providing an entirely different gaming experience from what users could experience at home.

In July 2016, Hero Entertainment and Omni formed a joint venture. After subsequent $7.2 million Series A investment round, Virtuix ceased all consumer sales to focus on the commercial market.

Goetgeluk said it was tough adjusting mentally to the change, but he felt reinvigorated, as if his own VR product had earned an extra life.

The Omni now sits in venues across China, and the market is growing quickly. Today, there are 140,000 internet cafes in the country, many of which are adopting VR. But it’s not just China. Other high-production arcades are popping up around the world. VR arcades alone are projected to bring in $8.5 billion by 2020.

Goetgeluk says most arcades purchase two or three Omnis at a time, but some, like those in Hong Kong and Turkey buy upwards of a dozen, and they’re starting to gain traction in the U.S. as well. The Omni can now be found in at least 30 locations in the United States from Sacramento to New York City and almost everywhere in between.

Goetgeluk is far from satisfied. A chronic workaholic with an obsession for detail, he says he still works from 7am to midnight every day on “every facet of the business.” He told me the week before we first met, he visited four countries in five days speaking with potential clients—Poland on Monday, Holland on Tuesday, Russia on Wednesday and Thursday, and Spain on Friday and Saturday. But he’s recognizing that it’s time to slow.

“I just had a newborn, 5-week-old baby,” he says, beaming. “So I have to be mindful of my wife, of my baby, so I can’t just travel as much as I want to. I have to balance that a bit, but I don’t mind.”

Goetgeluk says he and his small Austin-based team sold more than 2,000 Omnis in 2017 to malls, gaming arcades, and various other venues around the world—each for around $7,000.

The company also added a suite of omnidirectional compatible games, dubbed Omniverse—some made in-house, others produced by various VR gaming studios—to streamline the experience for venue owners and create a new revenue stream. Virtuix gets a few cents from clients for every minute played, a stable form of income in a volatile industry.

Goetgeluk is hoping his company will reach profitability this quarter and become one of the first VR startups to do so. As with other VR headsets, he sees potential for the Omni outside of the realm of gaming. It’s already seen a variety of uses, from supporting the treatment of brain disorders to helping soccer referees perfect their trade.

“The era of good VR is here,” Goetgeluk says. “A few years ago we had a lot of bad VR. I mean, Google Cardboard-like VR. It really hurt the VR industry. It was so underwhelming that we now have to explain to people that the Google Cardboard they tried is not really the good VR we’re talking about.”

Goetgeluk still believes virtual reality is set to be the next big thing in gaming, but he knows it’s going to take time.

“Is VR a niche market? Well, maybe it still is, but is it going to be niche five years from now? I don’t think so,” Goetgeluk told me enthusiastically. “Commercial VR, is it niche now? You could say that, but it may be in every mall in every city and entertainment center five years from now.”