ISIS and encryption are a combustible combination: An ideology and technology that together are driving a global debate that’s about to hit Capitol Hill.

No matter what side of that debate you land on, however, it’s useful to keep an eye on how the world’s most infamous jihadist army is using encryption for security.

Whether you’re talking about white supremacists, jihadists, or democracy activists, extremist or subversive groups the world over—groups whose politics fall outside the mainstream and often against the powerful—have long been heavily invested in online security. This has driven U.S. officials like FBI Director James Comey to warn that terrorists and criminals are “going dark”–operating outside the reach of intelligence agents and law enforcement thanks to their use of encrypted communications.

In the last year, the Islamic State has found new ways to encourage more secure practices among their followers. The Afaaq Electronic Foundation (AEF), an arm of ISIS dedicated to “raising security and technical awareness” among jihadists, exists for the purpose.

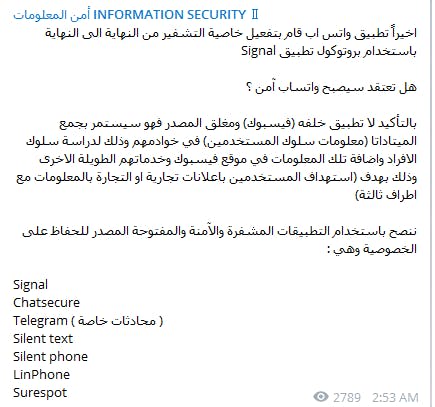

“We recommend using encrypted and safe applications and open-source to maintain the privacy.”

In reaction to the news that WhatsApp recently enabled end-to-end encryption for its more than one billion users, AEF took to its usual propaganda channels (social media networks like Telegram and Twitter) to recommend against using anything either owned by Facebook, like WhatsApp, or whose code is hidden and closed-source, which would shield it from independent inspection for “backdoors” that could give government spies access.

“We recommend using encrypted and safe applications and open-source to maintain the privacy,” the techie-jihadis wrote.

The Islamic State’s current roundup of app recommendations is a listicle of seven encrypted apps from all over the world: Signal, Chatsecure, Telegram (with encrypted chat) SilentText, SilentPhone, LinPhone, and Surespot.

On one hand, this isn’t new. After last month’s Brussels terrorist attacks, AEF broadcast similar messages. But there’s no doubt that at least some jihadis and their supporters are now using these apps. The level of sophistication and popularity is another question entirely.

In Washington, D.C., a Senate bill is expected in the next week that will effectively ban strong encryption in the United States by requiring companies like Apple or Facebook to decrypt communications and other data for the government. A leaked draft of the legislation is already at the center of a political firestorm.

But would it stop ISIS from using these apps?

Likely not. Only two companies on that list (Open Whisper Systems, which develops Signal and whose technology powers the encryption enabled in WhatsApp; and Surespot) operate within the United States—meaning they would be subjected to U.S. law. SilentText and SilentPhone are Swiss-based creations. LinPhone is French.

In Switzerland, a political war over Internet privacy and encryption is being won by anti-surveillance forces. In France, backdoors in encryption have been repeatedly shot down by the ruling government despite multiple recent deadly terror attacks, a testament to how strong the opposition to the idea of weakening encryption is inside the country.

“Actually, until very recently, the U.S.A. was the ideal place to start a privacy-enhancing service or technology,” Joseph Lorenzo Hall, the chief technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology, told the Daily Dot. “Our notions of free speech and the pro-innovator nature of our market tended to lay the groundwork for things like PGP [an encrypted email protocol].”

While the rest of the world wrestles with privacy and encryption thanks to violent groups like ISIS, the future of online security in America is being decided now in the halls of power—and, thanks to a largely free and robust Internet, from citizens connected in every corner of the United States.