In museums and ancient cities across Iraq and Syria, Islamic State extremists have destroyed countless priceless artifacts, some dating back as far as the Roman and Persian empires. In the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, militants smashed ancient art and antiquities in the Mosul Museum with sledgehammers, and broadcast the destruction in a video that went viral earlier this year. Around the same time, bulldozers and explosives destroyed the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud, built around 1250 B.C. In Syria, UNESCO World Heritage Sites and Syrian heritage are targets of looting and destruction.

The United Nations characterizes the Islamic State (ISIS) attacks on ancient culture and historical heritage sites as war crimes. Militants target such cities and artifacts because pre-Islamic culture that includes Christian and Jewish religions is considered idolatrous, and ISIS believes it is their duty to eradicate the ancient heritage that differs from their extremist beliefs. Some artifacts, however, are looted and sold to finance the group’s military efforts.

As Iraq and Syria lose countless and irreplaceable pieces of art and culture, historians, activists, and artists are doing their part to try and save the region’s history before it turns into dust.

In San Francisco, Morehshin Allahyari is tackling the loss of artifacts from an artistic perspective. We discussed her 3D-printing preservation project on a couch in AutoDesk’s Pier 9 offices, where artists-in-residence spend months working on engineering, art, and programming concepts using giant laser-cutters, metal and wood shops, and multiple kinds of 3D-printers. Allahyari just finished her four-month residency.

Allahyari is an Iranian-born artist and activist who moved to the U.S. in 2007 after studying social and media studies at the University of Tehran. Her passion for using technology to approach political, cultural, social issues around the world inspired projects like “Dark Matter,” a humorous series that combined and 3D-printed objects that are forbidden in Iran. Allahyari’s latest work has a much more serious undertone—with 3D printing, she’s recreating original antiquities destroyed by ISIS at the Mosul Museum for a new series named “Material Speculation: ISIS.”

“There is no way to replace these artifacts. All that is gone. It’s destroyed,” she said. “The least we can do with this technology is to find a way to, as accurately as possible, recreate them. To include all the knowledge and information about them just as a way to keep the history alive.”

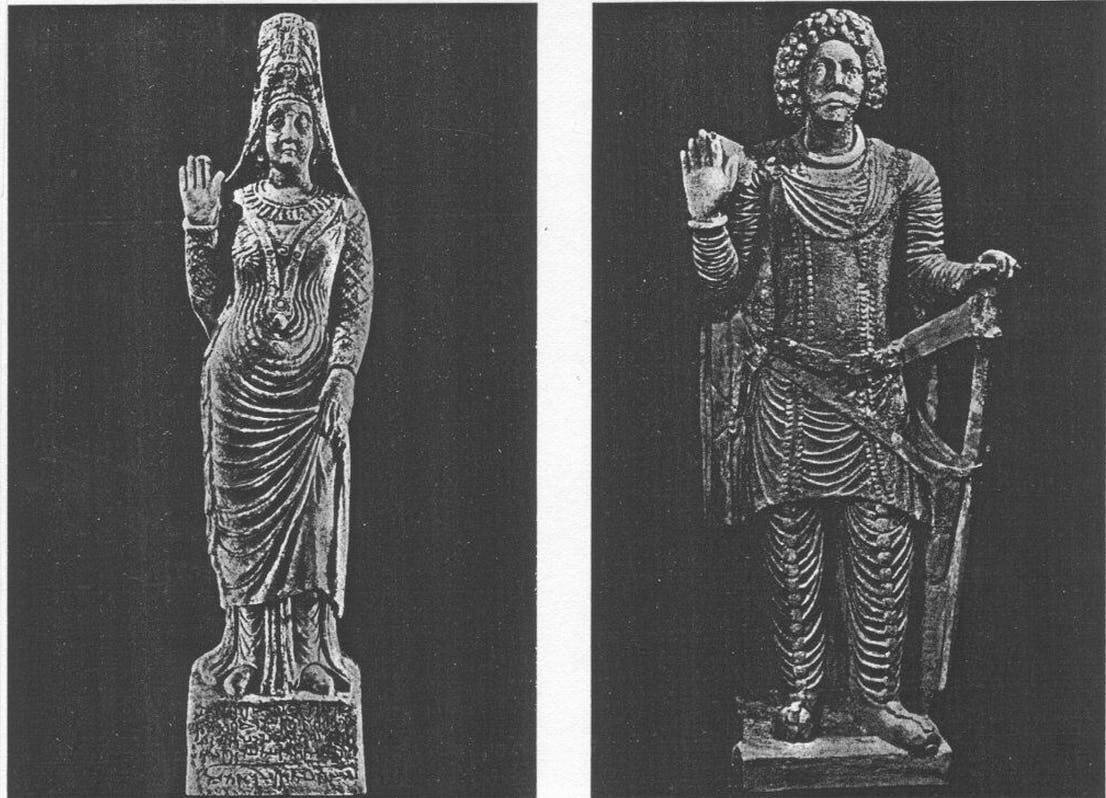

Allahyari’s creations recapture original pieces from the Assyrian and Hatra time periods that ISIS targeted for destruction. When completed, she will have between eight and 10 pieces, standing no more than 10 inches tall, created with clear, 3D-printed material.

A memory card floats inside each piece, suspended in mineral oil to preserve the data—the artifact’s information is stored so anyone can pull out the plug that holds the card without destroying the piece, and look up the historical data about the original item, as well as the information about the 3D-printed design.

Despite the artifacts’ priceless nature, the Mosul Museum had no catalog of what was in the museum, or what, exactly, was lost. Allahyari had to conduct extensive research and interviews with historians, archaeologists, and researchers including university students in the Middle East and the U.S., and representatives from the British Museum, to determine which pieces were lost, and which of those were the original artifacts. One of her first pieces, an original lamassu winged bull statue was particularly well-known, and a copy of it still remains in Persepolis. ISIS obliterated the original.

“I was amazed how little information was out there about these artifacts,” she said. “When I started the project I thought it would be really easy, and that the Mosul Museum would have a catalog.”

The undertaking required research in English, Arabic, and Persian, along with the help of Christopher Jones, a Ph.D student at Columbia University, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth art history assistant professor Pamela Karimi, Tehran University student and friend of Allahyari’s, Negin.T, and Hatra researcher and historian Wathiq Al-Salihi. AutoDesk colleagues Shane O’Shea, Sierra Dorschutz, Patrick Delory, and Christian Pramuk assisted with the 3D modeling.

The research process was complicated thanks to convoluted or non-existent records. One 400-page document about Hatra that Allahyari received from Jones was scanned backwards—whoever scanned it did not realize Arabic is read from right to left.

Eventually her research turned up a handful of items and the photos that accompanied them. Normally when an object is prepared for a 3D printer from a photo, the object is captured from multiple angles to produce a 3D-rendering of the item which a designer can optimize for a printer. Unfortunately, all Allahyari had were one-dimensional photos, many of which were poorly-scanned in black and white. There were only a handful of photos, she said, and what was destroyed was impossible to reconstruct from photos alone.

It took three weeks to one month to create each piece, going back and forth between the modeling process based off grainy historical images and prepping each item to be 3D-printed. The artifacts needed to include a space for the memory card, and be modified to scale from whatever grainy image files Allahyari could get her hands on.

Allahyari reproduces the pieces on a Objet 3D printer, which prints in resin instead of plastic. The resin is printed layer by layer, and a UV light hardens the material, creating a clearer final product than what we’re used to seeing emerge from consumer 3D printers like MakerBot.

“Material Speculation: ISIS” could be described as preservation of culture or a historical research project, but to Allahyari, it’s all about the art.

“Before anything else this is an art project,” she said. “It has all these poetic, emotional sides to it, and my own connection to these objects. Iran and Iraq share this history, for 2500 years, they were all part of the same empire.”

Allahyari looks at the recreation of artifacts from an artist’s perspective, examining how artists can use their positions to respond to social issues or political events. The memory card might retain the historical data, but the items themselves are a reflection of her own connection and reaction to the destruction of an ancient culture and her attempt to preserve it.

To push the boundaries of 3D-printing and art in collaboration with other technologists and designers, Allahyari and collaborator Daniel Rourke are working on the “The 3D Additivist Manifesto,” a concept that calls upon creators to come up with new and different ways of using 3D printing in ways that range from boundary-pushing to provocative and weird.

While Allahyari reproduces artifacts here in the U.S., a number of programs sponsored by international backers are trying to preserve cultural heritage from ISIS territory before militants can destroy it.

“Monuments Men,” archaeologists, artists, and academics who took their nickname from the cultural preservationists of World War II, enter ISIS territory in an attempt to document the antiquities and ancient cities with cameras and notebooks. Preservationists visit sites damaged by war in Syria, repairing what they can and saving what still remains by propping up sandbags and shrouds to protect the artifacts. Support for the Monuments Men comes from representatives at institutions like the Shawnee University in Ohio, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, and the Smithsonian Institution.

In Iraq, preparations are underway to catalog these physical antiquities down to the tiniest piece. Though it remains in an area protected by the Iraqi government outside of ISIS control, work is underway at the ancient historic site of Babylon to log the area and preserve what remains of the city.

Babylon’s antiquities will be able to be recreated in the event of the site’s destruction—unlike the Mosul Museum’s dearth of information. Meanwhile, Iraqi academics and officials teach locals and conservationists simple ways to help chronicle antiquities, like taking GPS-enabled photos of artifacts on their mobile phones, the New York Times reported.

Project Mosul is also trying to safeguard the history lost both from the Mosul Museum and other historical sites across Iraq and Syria. The organization is using crowd-sourced images to create files available for 3D-printing in an effort to save and open-source the artwork lost or at risk of being destroyed by ISIS.

“It has a practical part,” Allahyari said. “But for me it’s a gesture toward talking about destruction, and our position as artists to respond to these things.”

Allahyari is not sure where her artwork will eventually end up, as she’s not quite done with the set. She’s staying in San Francisco, but her work might travel across the country, or perhaps the world. The data contained in each memory card with the blueprints for creating the historical objects will be open-sourced to the public, ensuring preservation of the culture beyond what can be contained in mineral oil. Because, just like the originals, it’s possible they won’t last forever.

Photo via Morehshin Allahyari