Members of Congress convened Wednesday to discuss one of the most pressing threats in the world of cybersecurity: the smart appliances in your home.

On Oct. 21, some of the most popular websites in the country, including Twitter, Amazon, Netflix, and Spotify, were taken offline by a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack that targeted Dyn, a company that manages Domain Name System (DNS) servers. The attack utilized vulnerabilities in connected devices—DVRs, security cameras, refrigerators, thermostats, etc.—to essentially create a bot army that overwhelmed Dyn’s servers with traffic.

In some ways, the Dyn attack was a blessing in disguise: It didn’t involve critical infrastructure or medical records, for example. Researchers claim the attack was not the work of nation-state actors, as immediately suspected given its timing before the 2016 election, but likely stemmed from contributors to Hack Forums, a website where hackers offer DDoS attacks for hire. A Daily Dot investigation found such services offered online for as little as $20, though the price varies significantly depending on the length and intensity of the attack.

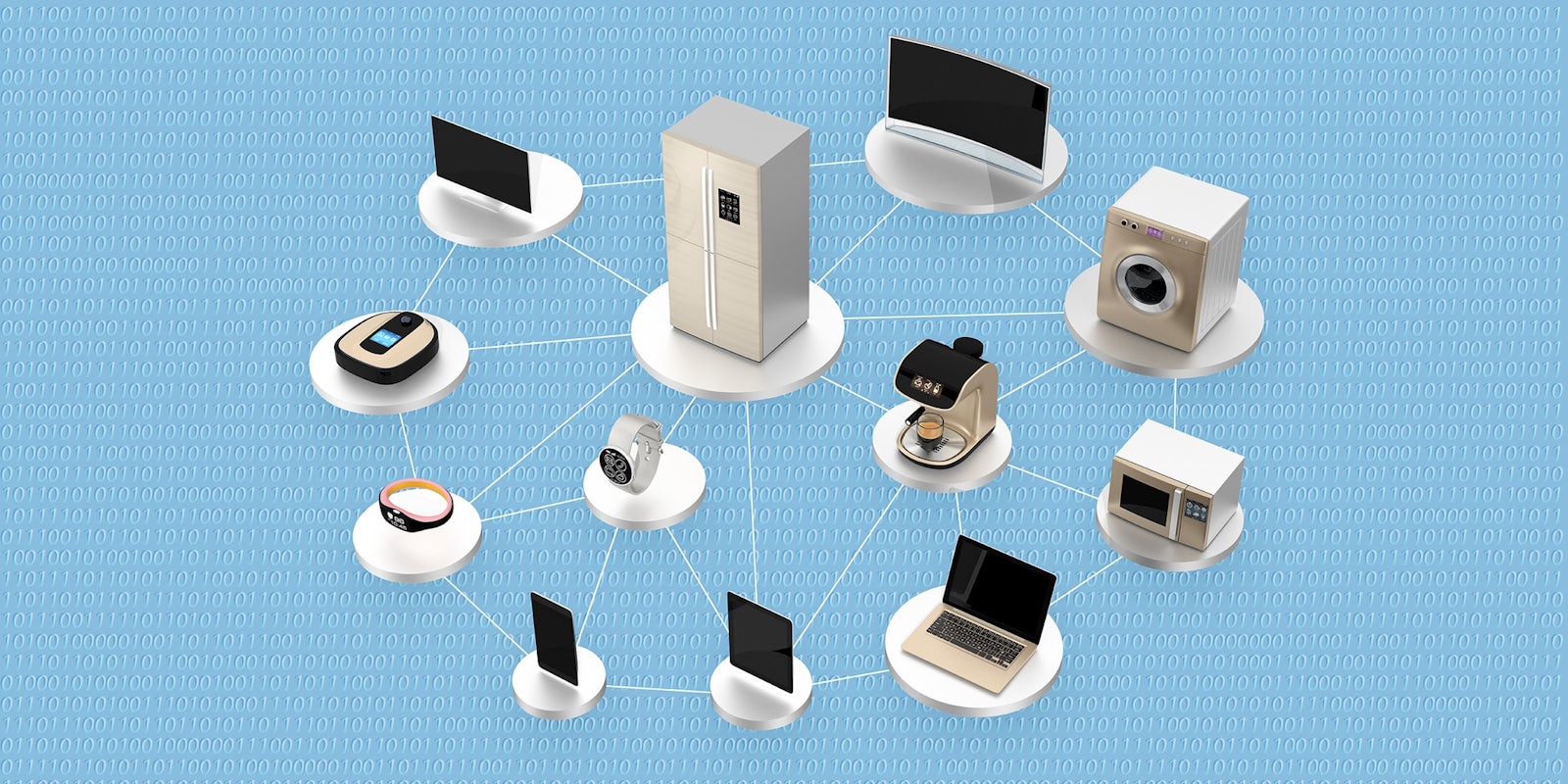

From a technical perspective, the Dyn attack was crude and unsophisticated, which is exactly what made it so alarming. For many internet users and politicians, it served as a jarring awakening to the vulnerabilities and potential security implications of the so-called Internet of Things (IoT).

The U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce held a joint hearing Wednesday between its subcommittees on communications and technology and commerce, manufacturing, and trade to better understand the role of smart appliances in the Oct. 21 cyberattack and others like it. The underlying message of the meeting was clear: “We believe the recent distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks which have been increasing dramatically in frequency and scale since September, have been a ‘shot across the bow,’ and we need to prepare for the worst,” Craig Spiezle, executive director of the Online Trust Alliance, a nonpartisan think tank, said in a statement for the committee.

As Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) noted, Americans own an average of 3.4 IoT devices, and there will be 50 billion devices online by 2020. Each of those could pose a security risk, one that could affect hospitals, businesses, and other essential services. A recent study found that a DDoS attack could have a financial impact of up to $250,000 per hour.

But how exactly to best deal with the many challenges posed by the Internet of Things is still very much up for debate, as the Energy and Commerce Committee meeting made clear.

The three expert witnesses—Dale Drew, the chief security officer of Level 3 Communications; internet pioneer and leading security expert Bruce Schneier; and Dr. Kevin Fu, CEO of Virta Labs—each made a push for greater government oversight or regulation of IoT devices, though their recommendations differed slightly.

“Nothing motivates a government into action like security and fear.”

Drew focused on the development of a set of security standards to guide product manufacturers. While that standard may not apply to products created outside the U.S., it would create a significant ripple effect. “We need to start with standards and then apply pressure,” he remarked. Likewise, Dr. Fu emphasized the need to incentivize executives to focus on security, the same way they might prioritize profit margins or time to market, to ensure that it’s “built into IoT devices, not bolted on.” He wants there to be a focus on the “pre-market” and to help give developers the opportunity to prioritize security protections.

Perhaps most surprising, Schneier delivered a strong call to action, stressing that the market has failed consumers and now needs government intervention to correct course. “It’s not a matter of government involvement: It’s a matter of smart government involvement or dumb government involvement,” he said. Schneier recommended the creation of a new agency as one potential solution, the reason being that every device—planes, cars, phones, etc.—is now essentially a computer, one that potentially crosses multiple government agencies. “We’re going to have to figure out rules that are central,” he stressed.

That the meeting took place on the cusp of a Donald Trump presidency, one that will look to lessen government regulation and infrastructure, was not lost on the committee. “If it takes new agencies, new regulations, we’re dead in the water,” Anna Eschoo (D-Calif.) acknowledged. “Our country deserves better.”

Greg Walden (R-Ore.) quickly asserted that this was a bipartisan issue, and Schneier referenced 9/11 to illustrate how quickly the U.S. government can move with the right motivation. “Nothing motivates a government into action like security and fear,” he said.

“It might be that the internet era of fun and games is over, because the internet is now dangerous.”

The consensus between the expert witnesses, however, was that this issue is bigger than mere consumer awareness and that it’s unfair to force consumers to “shore up lousy products,” as Schneier put it. There’s an inherent disconnect between the consumer, the manufacturer, and the damages their products might cause—perhaps unknowingly—to a third party. And even if that gap was somehow closed, if it’s not affecting their bottom line, there’s little incentive to practice good “security hygiene,” and it would take significant effort to do so.

That’s why, given the security risks involved, the witnesses collectively argued the IoT industry needs some sort of governmental oversight, even if it potentially hampers technological innovation.

“Yes, it will [restrain innovation],” Schneier acknowledged. “I don’t like that, but in the world of dangerous things, we constrain innovation. You cannot just build a plane and fly it. … It might be that the internet era of fun and games is over, because the internet is now dangerous.”

It’s important that security concerns in IoT devices are addressed now, before the market expands even further, the witnesses stressed. As Schneier noted, there are bigger issues on the horizon. “We haven’t even started talking about actual robots.”