Every day, nearly half a million pilgrims visit India’s richest temple, at the southeastern town of Tirumala, to pay homage to Lord Swamy Venkateswara, the Hindu god of preservation. In January this year, amid the crowd of thousands at the temple, popularly known as Tirupati Balaji temple, a man stole around $1,200 in cash.

Security soon found out the culprit. He was identified using footage from nearly 3,000 closed-circuit televisions (CCTV) on the premises.

Three months later, the temple launched a facial recognition technology (FRT) system where pilgrims, before visiting, first register online with their photograph and an identity card issued by the Indian government.

At the temple’s entry point, all pilgrims have their photographs taken. These photographs are cross-referenced with the registration database as well as the temple’s historic CCTV footage for the last three months to identify disruptive visitors, pilgrims with criminal histories, and possible instances of impersonation.

Only when the system grants approval are pilgrims allowed to proceed with their worship.

The result? The Tirupati Balaji Temple knows everyone in the crowd of half a million.

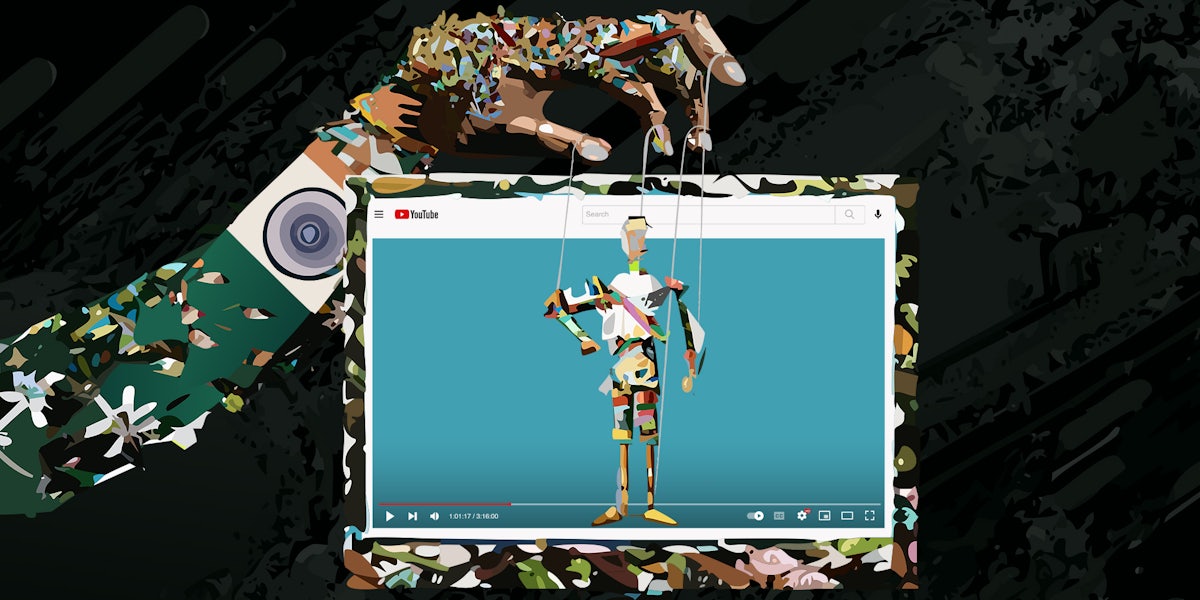

Unchecked FRT is a reality in many authoritarian countries, but India stands out as a place where this Orwellian technology is becoming obligatory for worship. And as Modi’s right-wing Bharatiya Janata party flexes its insatiable authoritarian urges, it is using these massive crowds at places of worship as testing grounds for a new digital panopticon.

The temples, which have the highest footfall among the public places in India, provide excellent experimental grounds to test the advanced surveillance technology in real-time and with an active, constantly moving crowd.

Srinivas Kodali, an independent data researcher, told the Daily Dot, “This profiling idea is not limited to just crowd control in densely populated spaces … This is an experimental ground for the Indian government to test and advance their surveillance FRT to real-time large crowds.”

Tirupati Balaji temple, with a net worth of over $30 billion and daily donations of $27,000, isn’t the only religious institution in India in the race to adopt the latest tech. Following in the footsteps of Tirupati Balaji, Ujjain’s Mahakal Lok temple, another prominent Hindu pilgrimage site attracting millions of visitors, spent $1 million to integrate FRT and artificial intelligence (AI) into its temple.

The AI in Ujjain Mahakal Lok oversees devotee activities, utilizing footage from nearly 500 CCTVs to predict foot traffic and map pilgrim’s behavior, aiming to avoid unruly behavior such as pickpocketing.

Now, numerous other temples are also racing to employ the latest technology for monitoring devotees.

“These may look like isolated cases of FRT,” said Kodali, “but such advanced systems are being installed throughout India. We are now in a post-FRT world.”

The obsession with facial recognition technology in India is on the rise. Cameras are ubiquitous, capturing everyone. There are at least 170 active FRT systems in India, according to the Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), predominantly implemented in the name of governance.

In the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, where the Tirupati temple is situated, there are at least eight known FRT systems installed.

Private entities in India are not far behind. Chaayos, a popular tea chain with over 200 cafes, and the fitness brand Cult Fit, with hundreds of gyms, also employ FRT.

And universities like Amity implemented FRT for enhanced security so only students can enter campus premises.

All these are test cases for India’s BJP government developing the National Automated Facial Recognition System (NAFRS)—a potent, all-encompassing FRT system designed to identify, track, and apprehend criminals across the entire country.

While pushed in the name of progress as part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Digital India initiative, the Indian government has used FRT to persecute minorities and control a population rebelling against it.

In 2021, during mass protests against the privatization of farming, Delhi police identified protesters using FRT. Similarly, in many protests in India against the Hindu far-right, protestors were identified using FRT.

Now, expansive systems will make the matter all the worse, as these temples show how large crowds can be readily mapped, people traced in an instant.

The IFF, an Indian non-profit organization dedicated to digital rights, issued a legal notice to India’s Crime Records Bureau, raising red flags about the potential surveillance outcomes of the NAFRS. It flagged that this all-surveilling system would disregard digital privacy and the rights of citizens.

In its response, the government dismissed those concerns and claimed that its algorithm merely automates a policing process already done by hand.

“Very little is known about NAFRS as the tendering process is very opaque,” Kodali said. But while the program will roll out in 2025, the push in temples is part of a public-private partnership that allows the government widespread access to a well-tested system.

The Tirupati temple is run by a trust called Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD), which is under the control of the state government of Andhra Pradesh.

Similarly Ujjain district administration controls the Mahakal Lok corridor, renovated recently at a cost of $42 million.

Privacy International, a London-based organization that has expressed concern about surveillance outsourcing and other forms of public-private partnerships, said, “Governments are collaborating with private companies, often with very little transparency.”

In a blog post it noted, “Surveillance outsourcing often seeks to exacerbate governments’ already unnecessary intrusions upon our everyday lives and undermine our fundamental freedoms. It does so by blurring the lines between private and public spaces as well as by normalizing surveillance.”

Privacy International argues that entrusting private organizations with “policing communities ultimately means more abuse, discrimination, and inequality, undermining democracy.”

In early 2023, when FRT was implemented by these temples, there was also no data protection law in India.

In the summer of 2023, the Indian Parliament passed a data privacy law, one that prioritizes mass governance over individual privacy.

However, even after the law passed the Indian parliament, there is no clarity as to when it will be applied.

“The new law leaves room for the deployment of this Orwellian technology for various purposes. Unless specifically regulated by law, there are no prohibitions on the use of biometrics or facial recognition for any purpose,” said Prateek Waghre, IFF policy director. “Broadly speaking, with this weak law, mass surveillance will become normalized in any space citizens use, whether public or private. Temples are not the only places implementing it.”

“From temples,” Kodali said, “FRT will expand to every space of public life. The idea is to create criminal profiles from the crowd … these systems are not going away,” Kodali said. “Rather these isolated systems, when connected with India’s crime record bureau, will create a country-wide advanced system that will monitor every movement of the citizens.

Kodali’s dystopian warning regarding the integration of sensitive data of millions with crime records is fast becoming a reality at the Ujjain Mahakal Lok Temple.

Ujjain Mahakal Lok is in the process of linking the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) and its all-encompassing criminal data to the temple’s algorithm governing its facial recognition system, Roshan Kumar Singh, who oversees the temple administration, said.

“If any person wanted in any criminal activity enters the temple, then we are able to identify them [using the NCRB Data]. We will then pass on that information to the local police.”

Apart from identifying criminals, Roshan argued that through this tech they can obtain an exact count of persons visiting the corridor and temple premises, which aids in crowd management.

“There are other analytics as well,” he said. “We also geo-reference certain areas. For example, in the corridor, we have electrical areas and statues that cannot be touched by any person. So, we have geo-referencing for these areas. If anyone reaches these areas, security will be alerted.”

It’s all being done under the guise of easing the process.

Ujjain Mahakal says it trained its AI to handle multiple visits by the same pilgrim.

“For pilgrims who visit the temple daily after their first registration with our server they need not present any ID on subsequent visits,” Singh said. “Their faces will be scanned, and the system will proceed.”

Reducing overcrowding is also Tirupati Balaji Temple’s goal. L.M. Sandeep, General Manager for IT at Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, told Daily Dot, “We use facial recognition for accommodation, room allotment, and sarva darshan (pilgrimage for all). In the case of sarva darshan, we capture a picture of each person at the gate and provide one free laddoo.”

Laddoo is a traditional Indian sweet offered as prasadam, a devotional offering to devotees after thanksgiving to god.

When asked about data protection in place for processing sensitive data, Roshan said, “We are complying with all the rules and regulations in place. We have our partnership with Telecommunications Consultants India Limited (TCIL), and they are experts in this area.”

Meanwhile, Sandeep said its temple retains “the data for one month. In our own data server, we keep it for three months, and then we delete it.”

However, the new systems, supposedly built for ease of pilgrimage, also leave out many in India.

Megha Chawariya, a 36-year-old mother of two who works as a domestic worker in Delhi feels these new regulations reinforce a digital divide, excluding the poor from worship.

“Ujjain Mahakal Lok is one of the most important pilgrimages I have done,” she said. “I had the privilege to visit a year before the pandemic.”

In 2019, when she visited, no one was asking for a photograph. There was no mandatory registration for pilgrimage.

“However, now I cannot even think of visiting,” she said

If Megha wants to visit Tirupati Balaji temple, advance online registration is impossible. She either needs a mobile phone or a device to take her photograph that can be shared with the temple.

“I do not own a mobile phone,” she said. I do not have an understanding of the digital world. People exploit my situation without an internet connection or mobile phone. No one helps us to register or people who help to register take money for this. I can understand that crime has increased so they have come up with this technology. But this technology is now a divide between rich and poor.”

“Making such systems mandatory also means that there would be exclusion. Is saying no to our photographs clicked at a temple really a realistic choice?” asked Waghre. “Those who say no are seen with suspicion. It is not necessary that these initiatives are made for surveillance, but these techno-solutionist initiatives are often blind to surveillance concerns. In many cases, there is no option to opt out. There is often no concept of consent. What makes it heavily dystopian is the absence of checks and balances, making it open to abuse with very little protection.”

And soon, it will be everywhere.