If you’ve got a robust Facebook friend list filled with single people who use dating apps like Hinge or Tinder, chances are you’ve appeared as a mutual friend between two different matches.

When your face appears as a link between people, you legitimize their connection. You become a topic of conversation, an “in” to launch a potential relationship.

Even if you don’t use these dating apps yourself, your personal information can still appear, because when your friends started using the apps, they gave the services permission to access their friend lists to display in-network matches.

There’s no way to avoid appearing as a mutual friend unless you unfriend everyone using these dating apps or delete your Facebook account. Even if your friend list is private, you’re still visible to these apps as a friend of a user who opted into sharing that information.

The potential consequences could be discomforting. Let’s say there’s a person on your friend list whom you added years ago and about whom you no longer know anything. If he matches with one of your good friends, she might decide to go on a date with him in part because of your online friendship, which can be misconstrued as approval from her social group.

Carrie Goldberg, a board member at the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative and a lawyer specializing in Internet privacy and sexual-consent litigation at the New York firm C. A. Goldberg, PLLC, said she became upset with these dating apps after a friend mentioned that she showed up as a mutual friend with a match on Hinge.

“The person she Hinged with is somebody I passionately dislike and I muted him so many years ago that it was a surprise to me to learn we were still Facebook friends at all,” Goldberg told the Daily Dot in an interview via Twitter direct message.

Most of us have likely never considered this issue. What are the social implications of appearing as a mutual friend in an app we’re not even using? Sure, some people might text you when you appear in the app, and that could prevent friends from winding up with Mr. Wrong—or helping them meet Mr. Right—but other people might just take the mutual association as approval.

For Goldberg, being perceived as a middle-man between two potential romantic partners represented an invasion of privacy. Her professional experiences underscore the potential dangers and concerns associated with this accidental and unwanted facilitator role.

“I have many clients whose lives were ruined by people they met online—stalked, sexually assaulted, revenge porn,” Goldberg said. “Many of them have PTSD, which can be triggered by both knowing that you are roped into these dating services non-consensually, and worse, when mutual friends inquire about matches facilitated through you.”

Goldberg said that some of her clients feel so passionately about not appearing as a mutual friend in third-party apps that they have deleted, or considered deleting, their Facebook accounts to avoid it.

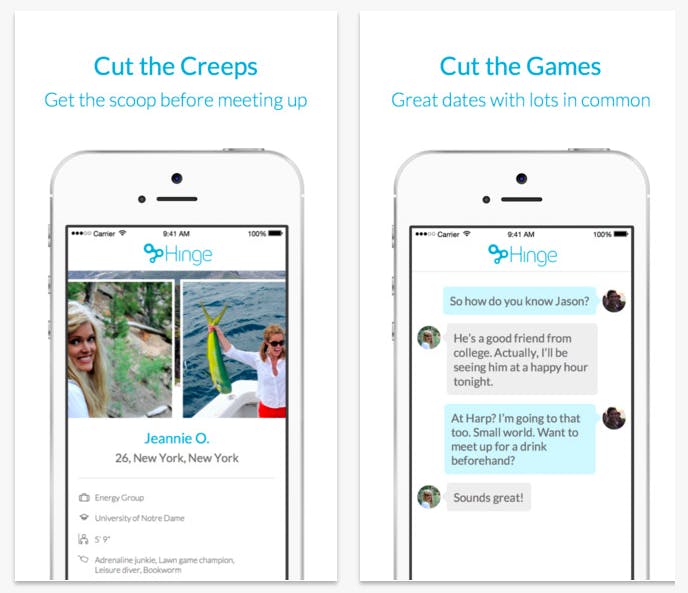

A spokesperson for Hinge said that it has never received complaints from people who feel uncomfortable appearing as a mutual friend. Once Hinge runs out of mutual friends to display, it starts pulling in friends-of-friends. Tinder doesn’t rely exclusively on social-network criteria, but it will show you how you’re connected to someone through Facebook friends.

“When a new user creates a Hinge profile, they opt-in to give Hinge access to their friend list on Facebook,” the Hinge spokesperson said in an email. “We do not have any information about those friends, including whether or not their friend list is private. Plus, we only show you to your friends.”

When asked whether or not this was an issue the company would consider fixing, the spokesperson said that Hinge would like to dig into this and see how it could be addressed.

Appearing as a mutual friend doesn’t just help with date-night conversation. A psychological phenomenon called the “social-network effect” is also at work here. When your friend or family member appears to approve of a potential partner, you’re more inclined to consider dating them.

A study published earlier this year in the journal Social Psychology Quarterly laid out three different ways social networks could affect dating. Researchers found that people frequently perceived a relationship as a positive decision if their friends or family approved of their partner.

In the case of network approval, network opinion verifies an existing mate choice and does not require that the recipient of the opinion question why the network approves. Rather, one can receive this affirming feedback and maintain the existing course of action (that is, remaining with a partner), perhaps heartened by the knowledge that the path one is on is a good one.

Services that rely on social accounts to facilitate the transaction of goods or services—like Airbnb, Uber, and Lyft—include a degree of social-network approval. You may appear to be a trustworthy human being because of your social network; and people will make decisions about whether or not to rent you an apartment or drive you home from the bar based on your Facebook account.

In most cases, though, you have to opt in before third-party services like Uber can access that data. Dating apps are unique in that you might appear simply because you’re connected to someone who opened up their personal lives to an app.

“Although the fine print in Facebook’s user terms may technically permit them to share this user information, it is nevertheless a major invasion to force users into becoming accessories to other people’s dating experiences,” Goldberg said. “Facebook needs to incorporate opt-out options into its privacy settings when it comes to it sharing our information with online dating platforms.”

Facebook has no control over what third-party services do with the data you share with them through Facebook Login. Your friends list might be private on Facebook, but once you give an app permission to access it, the app can analyze the list to determine whether or not its users have friends in common.

If you appear as a mutual friend in an app but you never used it, the app can only grab your name and profile photo. It won’t know anything else about you.

Dating apps share information even if you’ve specifically tailored your Facebook settings to prevent it. If you’ve set your friend list to be visible to “Only Me,” people visiting your profile can see that they’re friends with you, but not the other people you’re friends with. But that setting doesn’t carry over to dating apps, because users agree to share their data, which includes their friendship with you—and two people with that friendship in common can see that they have you as a mutual friend.

“For many apps, the social context of mutual connections is a great way to establish trust and make people feel more comfortable,” a Facebook spokesperson told the Daily Dot in an email. “We provide a way for apps to do this while ensuring that people have control over their own information.”

Dating apps that pull data from Facebook are still a relatively new way of engaging with potential dates, and the idea makes sense in theory. Friends have set one another up on blind dates for ages, and it’s not unusual to run into people at bars and make introductions that turn into relationships.

Theoretically, this also applies to dating apps—the bar scenario just becomes an avatar in a mobile app. But the current arrangement largely ignores the repercussions of forcing offline social norms into online services. The environment is not the same, and the person acting as the “friend” has no control over the virtual handshake.

“With these friend-of-a-friend dating apps,” Goldberg said, “we are forced to vouch-by-proxy for people with whom we may have the most tenuous of acquaintanceships and could unknowingly facilitate the matchmaking of a horrible match. . . or worse.”

The onus is on these apps to provide safe, inclusive spaces for their users, but what app-makers seemingly overlook is the impact on the unwitting mutual acquaintance—the person who isn’t using the application at all but is still “used” within that app.

“Online dating, and dating in general, is a personal issue,” Goldberg said. “They are not considering that some people have had incredibly negative online dating experiences and that it can be traumatizing to know that you are involved in it.”

Photo via samcaplat/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)