It’s hard enough to make money as an artist, but a career in digital art can prove especially tricky.

Once you’ve seen a GIF, you’ve consumed it. Money never exchanges hands. That’s convenient for the consumer, but not great for the creator.

Some GIF artists, such as Mr. GIF, have been able to obtain corporate gigs, lending their talents to major brands and TV personalities like Jimmy Fallon. But they’re the exception, not the rule. Others, like Max Capacity, have storefronts that are uniquely thematic but don’t necessarily feature GIFs. Most GIF artists, like myself, don’t have a way to monetize animations.

So when when I first read about Gifpop, I immediately dusted off my Facebook login and broke out the credit card with little hesitation. For $12, I was able to transform my GIFs into actual, real-life pieces of artwork, and each artist gets 80 percent of all sales from their GIFs. I had to buy three. When the packaged arrived earlier this week, I couldn’t open it fast enough.

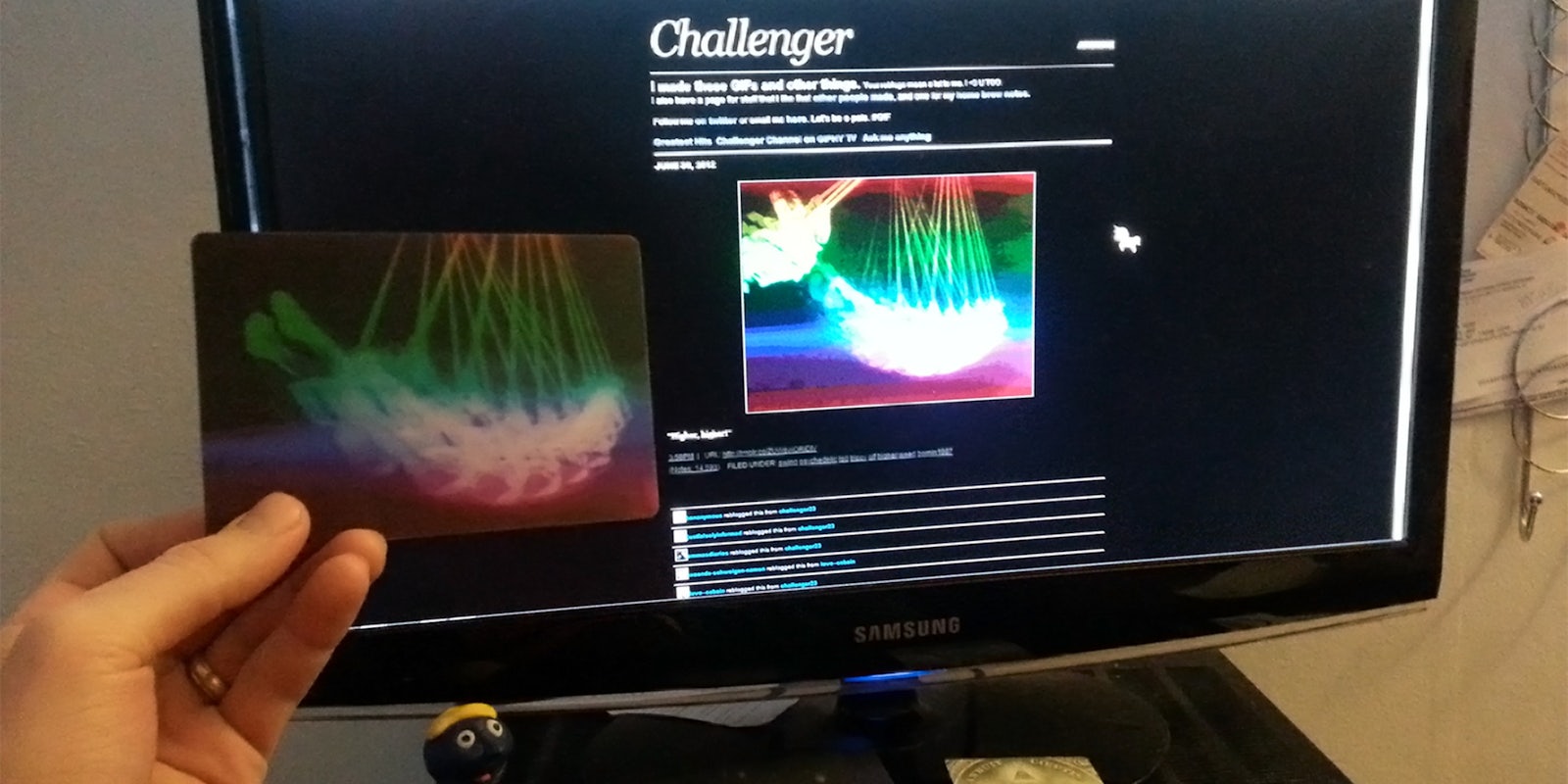

I was curious to see the limitations of the medium, so I picked two GIFs from my Tumblr and made another in Gifpop’s largest lenticular print—images made of angled plastic that give the illusion of movement and depth when you tilt them. Using Gifpop’s online system, you can select up to 10 frames from any GIF you’d like and turn it into a lenticular print. The size of the prints can vary from a small business card to a larger 5-inch square, but its best to select a size that is proportional to the height and width of the animation.

![]()

The print of the dollar bill with the winking eye got better results than the child swinging on a black background. As Sha Hwang, a Brooklyn-based digital designer and one half of Gifpop, explained, it all comes down to image selection and the number of frames used in the print.

“Clear movements help; shaky movements hurt,” Hwang said. “That’s one reason we’ve been limiting the frame selection to consecutive frames—we don’t want people uploading 10 distinct images and thinking it’ll come out looking okay! Getting a perfect loop in 10 frames is a sort of sweet spot for us right now, and it’s something all of our artists have been happy to work with. And a ‘best practices’ guide is something we really want to expand on.”

.@gifpop https://t.co/JvGwJy4MTo #gifpop #cool #thankyou

— Sneaky (@SneakyMission) December 17, 2013

Gifpop was started by Hwang and fellow designer Rachel Binx in November after their Kickstarter project collected $35,000—seven times their stated goal.

“We didn’t know what to expect, but were really blown away by the response, both from backers and press,” Hwang told me. “We started our Kickstarter being very adamant to ourselves that we wouldn’t end up being something that dragged on for years, and so it’s been a dense few months as we’ve worked to get Gifpop available to backers and the public.”

Gifpop has currently partnered with eight artists who can print and sell in bulk, including Mathew Lucas (89-a), Zach Dougherty (hateplow) and Lacey “lulinternet” Micallef, who has made GIFs for AMC, Frederator, and Tim and Eric.

Hwang hopes to expand that number greatly in the new year and improve the printing process even more.

“We’ve gotten inquiries from all over—from artists we’ve already been eyeing to artists doing incredible work we’ve never seen before,” Hwang said.

“I think we’ve hit on something that’s been a constant question for digital/video artists as a whole. Selling digital art has always been hard, and we think that many online marketplaces for digital art don’t have the artists in mind. Charging the standard gallery 50 percent fee for digital downloads of videos feels cruel and absurd. For us as designers and artists that hurts, and that’s why we’ve set our terms so generously, and I think that’s also what excites the artists we’re working with.”

Agreed.

Video and main image by Jason Reed