As computers, smartphones, tablets, and other emerging technologies make the world increasingly visual, it can be hard for the blind and visually impaired to experience it the way those of us with normal vision do. Readers and scanners exist, helping to blow up text sizes; text can also be printed in Braille, but a large swath of printed copy is still unavailable.

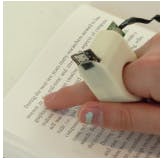

A group of researchers at MIT’s Media Lab, however, has been working to solve that problem and created the FingerReader: a device worn like a ring, that can scan and read words aloud in real time.

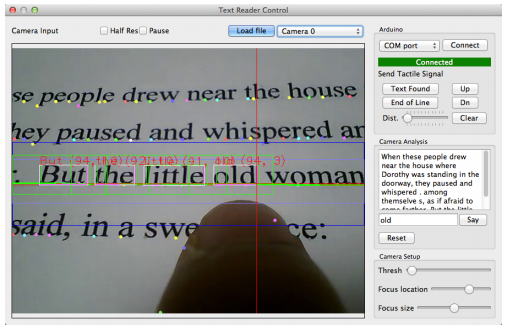

The FingerReader is made with a 3D printer and comes equipped with a tiny camera that scans words and read them back. A demonstration video shows a user placing her finger below the word she wants to read, sliding it along the page. The sensor will read and recite the word directly above the finger while looking ahead in order to process upcoming words. If a user’s finger strays from the line, the reader will indicate that with a small vibration.

The ring also vibrates when users have reached the end of the line and vibrates again once they’ve moved their finger to the next line.

The caveat is that the voice reading back the words is robotic and not quite as human as what we’ve become accustomed to with apps like Siri, but TechCrunch reports that the team is working to solve the issue.

The benefits of the product are easily realized for the blind and visually impaired, though developers were careful in not making FingerReader a solution exclusive to that audience. In April, Roy Shilkrot, a Ph.D student and researcher at MIT’s Media Labs, pointed out that the FingerReader’s intended user demographic like using devices that weren’t built just for them, and the team also hopes the tool could be developed for use in language translation.

Still, the benefits of the product allows for the blind and visually impaired can’t be ignored. “When I go to the doctor, there may be forms that I want to read before I sign them,” Jerry Berrier told the Associated Press. 62-year-old Berrier was born blind, but the FingerReader helps him while at work or in public, noting that he’s not familiar with another product that would be able to help him read in real time. Berrier manages a training and evaluation program that distributes technologies to low-income people from Massachusetts or Rhode Island who have lost their sight or hearing and also works at the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts.

Still, the benefits of the product allows for the blind and visually impaired can’t be ignored. “When I go to the doctor, there may be forms that I want to read before I sign them,” Jerry Berrier told the Associated Press. 62-year-old Berrier was born blind, but the FingerReader helps him while at work or in public, noting that he’s not familiar with another product that would be able to help him read in real time. Berrier manages a training and evaluation program that distributes technologies to low-income people from Massachusetts or Rhode Island who have lost their sight or hearing and also works at the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts.

“Everywhere we go, for folks who are sighted, there are things that inform us about the products that we are able to interact with,” he said. “I want to be able to interact with those same products, regardless of how I have to do it.”

The reader can read fonts as small as 12 points in size, so it wouldn’t be effective in reading small text on prescription drug bottles, but it does allow visually impaired people to tap into texts previously inaccessible for them. Shilkrot cited a study from 2011 conducted by the Royal National Institute of the Blind in Britain that found that only 7 percent of books were available in large print, unabridged audio, and Braille.

Shilkrot said the FingerReader can read print materials as well as text on computers, though the device has trouble reading on touch screen devices since touching the screen moves the page around and could produce unintended results.

There’s no word yet on how much the product could cost or when it could be released to the public. Researchers are still testing the product and are working to integrate more features into the product, such as making it work with cellphones.

Shilkrot and his team have been developing the product for three years, coding software and coming up with an efficient design. Patti Maes, an MIT professor leading the FingerReader team at the Fluid Interfaces Group at MIT’s Media Labs, told the Associated Press that using the reader is “more immediate than any solution we have now.”

H/T Associated Press | Photo by Chris/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)